The introductory panel to the exhibition “Never Broken: Visualizing Lenape Histories” — currently on view at the Michener Museum in Doylestown, Pennsylvania — states something remarkably important to the region.

But it isn’t in the words. It is the image on which the text is written: an overhead view of the Abbott Marshlands at the estuary where the Crosswicks Creek meets the Delaware River.

Joe Baker’s ‘Three Sisters,’ a 1997 oil on canvas from The John and Susan Horseman Collection, courtesy of the Horseman Foundation.

The land — part of Trenton, Hamilton, and Bordentown — is the site of what had been one of the largest Eastern settlements of Native American — as well as documentation of human activity there for 13,000 years.

It is also roughly in the center of the land called Lenapehoking (Land of the Lenape).

They are the indigenous people whose territory included all of what is known today as New Jersey, New York Bay and Hudson Valley, the eastern section of Pennsylvania, and northern sections of Delaware.

They are also the people whose culture was disrupted and then suppressed to near the point of extinction by European colonization, starting in the early 1600s.

The exhibition’s reference to “Never Broken” argues that the culture has never disappeared and that the exhibition is a type of reaffirmation.

The “visualizing” reference signals that the reaffirming will be done through visual art.

And, indeed, viewers will encounter ancient Lenape designs, European and Colonial depictions of the Lenape people, and new works by contemporary Lenape artists — who combine both Lenape and European and American art traditions.

The curators of what is being touted as the first exhibition of its kind are Joe Baker, participating artist and founder of the Lenape Center in Manhattan, and Laura Turner Igoe, the Michener Museum’s chief curator.

Three other contemporary artists are participating: Ahchipaptunhe (Delaware Tribe of Indians and Cherokee), Holly Wilson (Delaware Nation and Cherokee), and Nathan Young (Delaware Tribe of Indians, Pawnee, and Kiowa) — Delaware also being the name for the Lenape and their connection to the Delaware River.

As the curators note, the artists’ work “underscores the continuing legacy and evolution of Lenape visual expression and cross-cultural exchange, reasserts the agency of their Lenape ancestors, and establishes that the Lenape’s ties to the area were — unlike Penn’s Treaty — never broken.”

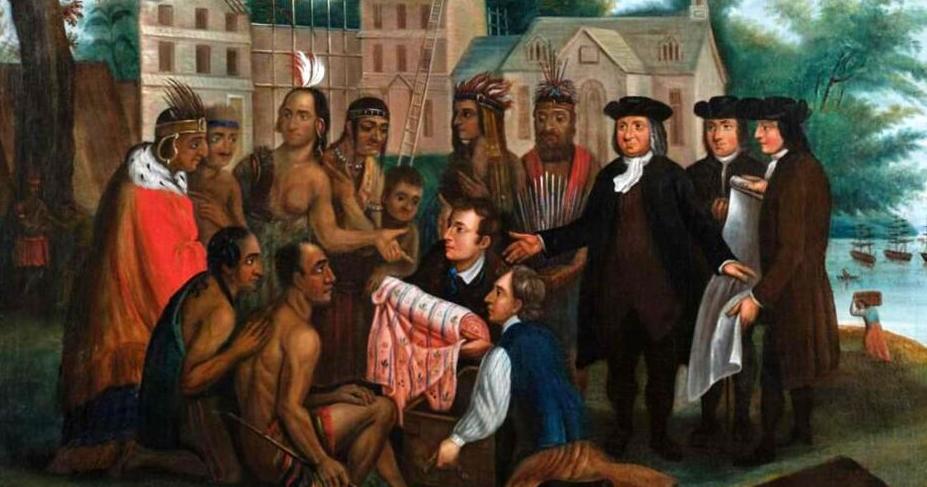

Noted Bucks County artist Edward Hicks’ 1845 version of Benjamin West’s Penn’s Treaty painting.

The treaty was William Penn’s 1683 agreement with Tamanend and other Lenape chiefs where Penn is quoted as saying “We meet on the broad pathway of good faith and good-will; no advantage shall be taken on either side, but all shall be openness and love. We are the same as if one man’s body was to be divided into two parts; we are of one flesh and one blood.”

Whereupon Tamanend replied, “We will live in love with William Penn and his children as long as the creeks and rivers run, and while the sun, moon, and stars endure.”

While some of the facts regarding the treaty are vague, it has been etched into the American imagination through visual art, mainly with American painter Benjamin West’s 1772 painting.

An area examining the impact of that painting can serve as one of several entry points to the exhibition of thematic sections connected by proximity.

As the curators note, the above mentioned painting “depicts William Penn (1644-1718), the founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, his agents, and merchants trading cloth and other goods for land from the Lenape, the region’s historical inhabitants. Commissioned by Thomas Penn (1702-1775) to celebrate the achievements of his father, Penn’s Treaty established a visual record for an event with limited documentation that occurred nearly a century earlier. It is therefore a perspective on history, not a factual account.”

The romanticized meeting became a popular and often reproduced image on various materials and “went viral in the pre-internet age. It appeared on textiles and fine china and was copied by other artists like the Bucks County, Pennsylvania, painter Edward Hicks (1780-1849). While Penn’s Treaty and its many copies and reproductions visualized the founding of the commonwealth as a peaceful transfer of land that was ‘never broken,’ Penn’s sons and colonists forced the Lenape out of Pennsylvania through deception and violence in the 1700s.”

Additionally, “During the 1700s, the Lenape population was decimated by introduced diseases and forced removals by European colonists eager to claim land. While some Lenape fled northwest to Canada and Wisconsin, the majority was forced to relocate to western Pennsylvania and Ohio, then west to Indiana, Illinois, Kansas, Missouri, and finally, Oklahoma.”

A New Jersey State Museum Lenape pottery vessel.

From this point, the exhibition viewers can easily move into a section that highlights the abstract lines on Lenape basketry and pottery — the latter found at the above-mentioned Abbott Marshlands and on loan from the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton.

The curators note that the Lenape used these designs more than 1,000 years ago and argue that the “abstract motifs drawn from nature illuminate the Lenape’s ancestral and spiritual connection to this land.”

The motifs are also a creative catalyst for Ahchipaptunhe, whose several new or specially commissioned large canvases use the designs for a four-series set of paintings that bear the Lenape names for earth, fire, water, and air.

The artist says that by doing so he “seeks to honor the achimwisák, or storytellers, in my artistic voice. A reminder that we are still here, forging paths for a future generation to look upon and see their connections back to Lenapehoking.”

The shape of the room and placement of objects suggests a movement to another area devoted to “Remembrance and Continuance.”

The former is realized by the installation that honors Xinkwikaoan (Big House), an important element in Lenape culture and spirituality.

It does so by erecting the frame of an actual structure used by the Lenape into the early 20th century to bring the community together, honor ancestors, repeat stories important to the people, and pay homage to spirits through voice, instruments, and movement.

Additionally, according to a quote from the last Delaware ceremonial chief, Charlie Elkhair (1854-1935), “the meeting house was used to keep anything down that was injurious to the people, such as floods, earthquakes, etc. So long as they kept it up we would raise good crops and everything else that was beneficial to the people. So that guidepost in the center is what protects the people on the earth. So long as that stands up the earth will stand.”

The curators also point out that “a carved and painted face on the central post faces east. It offers both gratitude and environmental protection in the face of climate change today.”

“Continuation” is reflected in the new work of Baker, another canvas painter, and Wilson, a sculptor, that generally covers the walls that of the space where the Big House resides.

Baker takes much from the Western European approach to painting to mix images of ancestors, cultural objects or activities, and significant imagery. The latter includes box turtle shell designs and patterns found in beadwork and stitching to convey, in one work, “a sense of movement, precision, and rhythm.”

A section of Holly Wilson’s ‘Bloodline.’

Wilson, also using traditional sculptural techniques, created what the curators call a “monumental sculpture” titled “Bloodline.” The work uses a series of smalls (metal) figures walking in a steady progression along a long wooden ridge that finely reflects the intent of showing works that “carry stories from the Lenape’s past into the present day and future.”

As the curators note, “Wilson made ‘Bloodline’ after documenting her family ancestry in order to enroll herself and her children as tribal members. She wished to give form to the names she encountered through this research. Bronze figures cast from cigars and found sticks traverse a cut locust tree that fell down in a storm. The figures on the right represent Wilson’s own children, both living and lost, and the lone figure on the left is Delaware Bobb, a Lenape leader who brought Delaware Nation safely into Oklahoma. ‘Bloodline’ tells a powerful and complicated story of loss, survival, and resilience through the artist’s family history.”

The fourth contemporary artist, Young, is a video and audio artist whose work is presented in the chamber theater adjacent to the Treaty painting.

His work is “Alëmi pëmëske” (He begins to walk). Its subject is the infamous 1737 Walking Purchase in which William Penn’s sons, who were the region’s proprietors, “coerced Lenape chiefs to confirm an incomplete deed from 1686 that outlined the transfer of land measured by a walk of one and a half days. After clearing a path in advance, three fast runners sped from modern-day Wrightstown to Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, traveling 65 miles in 18 hours and covering much more territory than the Lenape had anticipated,” note exhibition materials.

Young, in turn, has created a long playing video where he and a companion walk, in reverse, a portion of the route that colonists used during the walk to “unmake” the agreement that tricked the Lenape out of 1.2 million acres of land.

The film uses an “ominous soundtrack and monotonous passing of cars and trucks” to warn viewers “of the challenges and hardships that Young’s ancestors faced as they were forced from their homeland following the Walking Purchase. Images of beads and shells that were possibly used by the Lenape in trade and treaty negotiations appear throughout the video, reminding viewers of the broken agreements that led to the Lenape’s displacement.”

In addition to the exhibition, a recent panel discussion led by Baker with Ahchipaptunhe, Wilson, and Young continued the exploration of this returning or coming home to the land where their ancestors had lived for centuries before being displaced.

A consensus was expressed by Wilson when she said she was trying to find where she fit into the land, with Ahchipaptunhe adding that “I see Lenape names (in towns and bodies of water), but didn’t feel connected. I don’t know what an original home place means.”

Joe Baker and Laura Turner Igoe in the Big House frame.

They also shared similar thoughts on the current practice of land acknowledgements from institutions, with Baker asking others how they could “best serve our community (in a manner) that is beyond performity and more action based?”

“It is a good start. But it seems a hollow statement unless there is a meaningful action behind it,” replied Young, reflecting similar sentiments by the other panelists. “It can be as simple as education — humanize the experience. We are very much part of that (American) story. Meaningful steps, let’s start teaching about the specifics. “

As an example, Baker noted that exhibition held on Lenape land “is a fine example of a land acknowledgment that has turned into an action.”

The artists also turned their attention to creating art and discussed a sometimes external and internal dissonance.

Externally, it was the challenge of being stereotyped as a Native American artist with homogenized expectations — as one speaker put it, connections to “feathers, leather, and beads.”

Consequently, as Ahchipaptunhe notes, “You don’t want to be cast as a Native American artist. For a long time, I said I was an artist. But now, as a native person, I work as a Native American artist. I want to be called a Native American artist.”

As for a takeaway of both the exhibition and panel discussion, the following comments were made:

“My work is reflective of the poetry and the weaving,” says Ahchipaptunhe. “I was looking at the details … they open a story. It is the details that we overlook.”

Wilson said, “I have my stories and I want people to see history and what is happening now. Being seen is an important part … If you’re not seen, you’re history. I want people to hear and connect stories.”

Young followed by saying his hope was both would promote “an idea, empathy, and understanding that it matters to people in the region. It will help enrich greater sympathy and understanding and produce healing with these unfortunate parts of history.”

Baker added that the effort was “personal,” talked about the violence shown to the Lenape and members of his family, and said, “If we as humans don’t come to terms with the violence that formed this country I don’t think we’ll heal.”

Never Broken: Visualizing Lenape Histories, James A. Michener Art Museum, 138 South Pine Street, Doylestown, PA. Through January 14, Wednesday through Sunday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. $5 to $15. 215-340-9800 or www.michenerartmuseum.org.