A new Tim Burton exhibition, Dreamland, is open at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas, celebrating the 30th anniversary of The Nightmare Before Christmas.

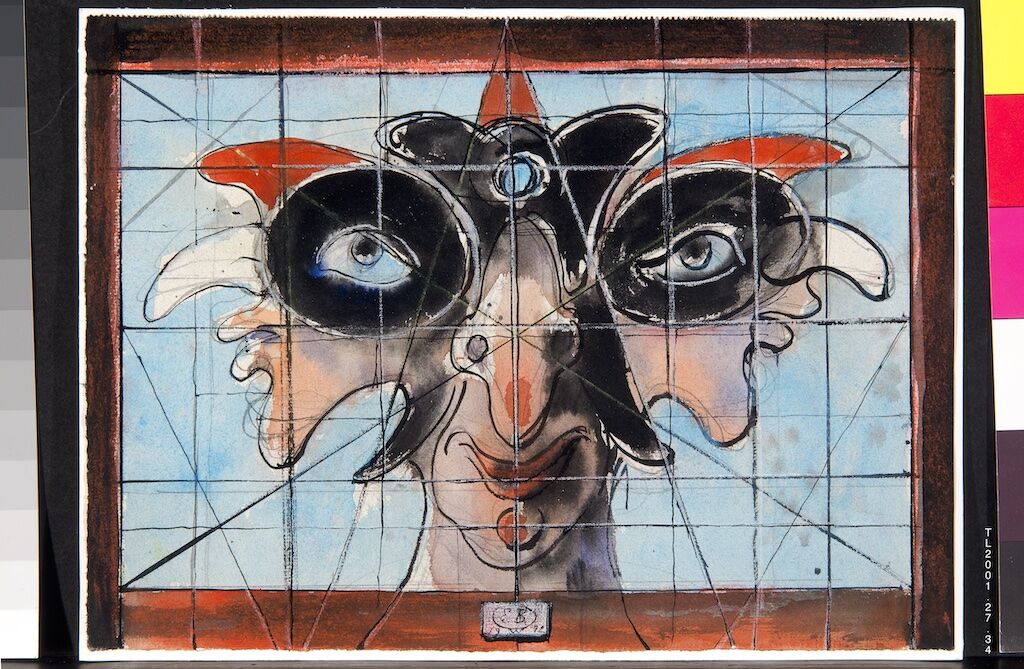

Dreamland celebrates the timeless appeal of the film, as models and characters from The Nightmare Before Christmas are placed in conversation with nearly 100 paintings, theatre designs, photographs, prints, sculptures and more from the McNay’s permanent collections featuring quirky characters and surreal worlds. Many of the works on display come from the McNay’s Tobin Collection of Theatre Arts. This is the most significant collection of performing arts ephemera in the United States.

Through the curatorial consideration of Tim Burton’s imaginative eye, artists featured in the presentation include Pablo Picasso, Käthe Kollwitz, Eugene Berman, Sandy Skoglund, Jim Dine, Katharina Fritsch, Carlos Mérida, Marilyn Lanfear, José Clemente Orozco Farías, Julie Speed and Diane Gamboa.

Dr. Matthew McLendon assumed leadership of the McNay Art Museum as director and CEO in February 2023, serving as the museum’s fourth director in its 68-year history. He speaks to blooloop about the museum and its mission, as well as this unique new temporary exhibition.

A multi-genre approach

After receiving Bachelor’s degrees in Art History and Music at Florida State University and his PhD at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, McLendon served for six years as the curator of modern and contemporary art at The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in Sarasota. In 2017 he became the director and chief curator of the Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia.

An influential leader, McLendon is renowned for his emphasis on community engagement and education, advocacy of cross-disciplinary programming and amplifying underrepresented and marginalised voices in the museum setting. He has spent a large part of his career as a curator.

“My background is perhaps a little non-traditional,” he says. “I spent the first half of my life in the performing arts.”

He originally studied, to be an opera singer. What drew him to opera was what Wagner called Gesamtkunstwerk, the ‘total work of art’:

“You have not only the music, you have the text, you have the design, you have dance, you have all the arts coming together in service of creating this fantastical performance that tests human physiology in so many ways. I had a fascination with that cross or multi-genre approach that is opera. Once I moved into art history, fell in love with museums, and decided that that’s where I wanted to devote my life, that interest in conversations between or among the arts never left me.”

Supporting artists

The artists he was initially drawn to were those investigating multiple genres simultaneously.

“That’s the foundational part of my curatorial practice,” he comments. “Then, as I was more involved in museums, I became very aware of how important representation is, how important it is for people to see themselves when they walk through the door. There are museological studies, philosophy, and academic writing on this, of course. But it was so clear how, as we want people to feel invested in their museums, they need to see themselves – or something that they recognise – reflected. That became very important to me.”

Understanding he had a great deal of resources and a platform at his disposal, he thought intentionally about how best to leverage them:

“I work with living artists for the benefit of living artists. So, I thought about the artists in the art ecosystem who are having the most difficult time attracting scholarly attention and being brought to the public’s notice. I started to become interested in working with emerging early-career and then mid-career artists.”

Dr. Matthew McLendon and the McNay Art Museum

This was what initially attracted him to the McNay Art Museum.

“I have always known about the McNay’s collection, of course, particularly its founding collection, the bequest from Marion Koogler McNay. My original scholarly background is in early 20th-century European art. The collection has so many remarkable works of European modernist art. I don’t think it’s over the top to say Picasso’s 1912 collage Guitar and Wine Glass is one of the most important works on paper in the country.”

“As I started to learn more about the museum through the search process to become the director, I realised that the McNay, from its beginning, and certainly in recent decades, has focused on the area of supporting living artists that I’ve been focused on in my curatorial and museum life.”

Another draw for McLendon was the McNay Art Museum’s Tobin Collection of Theatre Arts, a collection unique in America. This comprises around 12,000 works from the Renaissance onward, exploring theatre design and history, and including rare books on theatre history:

“I’ve been here about seven months now. Every day I feel like the proverbial kid going to the candy store: what fabulous new discovery am I going to make today? I came at a fortunate time, where we’ve had two major exhibitions back-to-back based on the permanent collection.”

Celebrating women artists

The first, Womanish: Audacious, Courageous, Willful Art, opened on 4 March and remained on view until 2 July as a special exhibition. This was envisioned as a second chapter to the 2010 exhibition, Neither Model nor Muse, which looked at the long history of collecting and supporting women artists at the McNay Art Museum.

“This was its second iteration, 12 years on, highlighting all of the work by women artists that had been brought into the McNay’s collection during that time. As a museum founded by a woman artist, it’s in the McNay’s DNA to support women artists, one of the most overlooked and underrepresented groups historically within the canon.”

The second of those exhibitions is, of course, Dreamland:

“I’m a big fan of Tim Burton, but hadn’t spent that much time with The Nightmare Before Christmas. I’m coming to understand what a cult classic it is for so many people. We have people on staff at the museum who watch it three times a year; they just love it. I was sitting in the galleries on Friday, and just listening to the people going through the exhibition. There is such a passion for it. People gasp when they stand in front of the maquettes, and they all take selfies with Jack Skellington.”

The appeal of The Nightmare Before Christmas

The Nightmare Before Christmas is also multi-generational:

“There are all of these families coming through; parents are introducing their little kids to The Nightmare Before Christmas. People enjoy getting to see the models and the maquettes up close, realising they’re scaled to cinematic size on the screen, and coming to a better understanding of the material itself.”

He adds:

“The curatorial team at the McNay Art Museum has used the Tim Burton material, which is known, loved, and has an almost, cult-like status, in conversation with the wider collection, both the theatre arts collection and the wider collections of the museum, as a kind of entree moment.”

The exhibition references other works in the collection through the lens of the works comprising The Nightmare Before Christmas to ask how the works converse; whether Tim Burton and an unassociated artist, as they conceived their creations, were being brought to similar or different visions, and exploring the elements informing those visions.

McLendon comments:

“There’s a wonderful moment in the exhibition with the Bone Crusher sculpture from the movie, and then a whole row of skeletons by other artists. It’s such a fantastic way of using the contemporary – and what people are familiar with – to then bring them into a conversation with artists that they’re not familiar with, to explore how artists can use the same motif or subject matter in different ways.”

What makes a great exhibition?

Exploring the question of what makes a great exhibition, he says:

“When I talk about this with students, I start with what I find to be the case when I walk through an exhibition, and I think it has failed. Exhibitions can fail when they try to cover everything on a subject. You can’t cover everything. You can’t answer all of the questions. I don’t even know if you can answer a question in an exhibition. When you are formulating your ideas for exhibitions, it’s important to have a strong question. But you need to be rigorous in editing that down to one idea, one thesis, that you then investigate.”

“I think of exhibitions as investigations. I don’t know that we can ever answer questions in exhibitions, but we can ask them, and get people thinking.”

He differentiates between the exhibition catalogue and the exhibition experience:

“From the catalogue standpoint and the scholarly standpoint, it is possible to ask important questions that haven’t been asked before. But I think that the catalogue does one thing, and the exhibition does another.

“If we’re talking about the visitor experience of the exhibition, it should be a strong question or set of questions. Ultimately, when I have gone through a successful exhibition, I keep thinking about it after I’ve left. I continue googling about it, or reading about it, or looking up reviews about it.”

Connecting with the audience

Additionally, it needs to be compelling:

“We create exhibitions because we’re excited about the subject. We need to make sure our audiences understand why we’re excited about this subject so that they’ll be excited about it as well.”

Increasingly, he adds, it is important to demystify the whole process. Throughout the history of museums, there has always been the notion of the curatorial voice as the authority:

“We are much more honest these days when we don’t have the answer to a question. I find that helps to demystify and to give people permission when they’re walking through an exhibition – to explain that it’s okay if they don’t have the answers, or if they don’t completely understand.”

Finally:

“What I think is one of the great life lessons of all time is the importance of editing. Success in so much of anything that we do comes down to editing rigorously, and asking ourselves, ‘Is this important? Is this necessary? Does this translate to the audience? Ultimately, that is at the heart of the successful exhibition.”

Dreamland at the McNay Art Museum

In the context of the Dreamland exhibition, identifying the thesis underpinning it, he says:

“I think the question is, how do we use the work of art in conversation? Dreamland was, of course, planned before I got to the McNay, but I think Scott Blackshire [Dr. R. Scott Blackshire], the lead curator of the exhibition, would agree it is about how we use the familiar to bring our audiences to an appreciation of the unfamiliar. That is beautifully done with Dreamland.”

In a world where war, climate change, economic crises and human rights atrocities vie for headlines, what are the opportunities and challenges facing the art sector?

“There is a meta and a micro level to that question,” he responds. “On the micro-level, we are all still reeling, in some way, from the pandemic. It changed everything. We will never go back to the way things were before the pandemic. That holds for every sector, and is, of course, true for the cultural sector. One of the most poignant things I’ve heard in terms of the challenges of the cultural sector is that we’re not competing with one another. We are, instead, all competing with Netflix.

“How do you get people out of the house to come to your concert, your play, your exhibition? We all think a lot about that, in museums and across the cultural sector. It goes back to the need to be really in tune with your audience. You have to be in partnership with your audience. You have to know what resonates with your audience.”

Rejuvenation through art

Dreamland, he contends, is a perfect example of that, and other programs at the museum also do it well.

“That is the constant,” he says. “How do we cut through the incredible amount of noise in all our lives to get to our audience? That is the micro that we are all dealing with. And it is exacerbated post-pandemic. because we all stayed home for a year or more.”

“To the meta-level of that question, the world is on fire in so many ways, both metaphorically and literally. We have to find and walk a very delicate line. If the museum is going to be relevant, it will be called to engage with what is most difficult in the world, especially if it is a contemporary art museum because that is what contemporary artists are doing, and that is what we look to our artists to do.

“Artists see the world in ways that we do not. Therefore, they bring our attention to things that we have missed. That is the power of art, through time. We are going to have to engage in those ways. We must be relevant. At the same time, people are desperate for moments of repose. We are desperate for moments of meditation, in the largest sense of that word. We must walk that fine line of dealing with the very difficult, but also giving people the opportunity to rejuvenate themselves through art.”

On beauty

He has, he explains, been thinking a lot recently about beauty:

“That is a very loaded term, but whatever it means to you, we need moments of pure beauty. That is something the McNay Art Museum can provide to our audiences. We have 25 beautiful acres of land filled with fantastic sculpture that brings you into a beautiful architectural experience of both the historic home and the new Stieren Center.”

The Stieren Center for Exhibitions, a collaboration between architects Ford, Powell & Carson, Jean-Paul Viguier of Paris, and the Paratus Group in New York, is a 45,000-square-foot pavilion for exhibitions and shows created from the Museum’s extensive undisplayed holdings.

“There are opportunities, of course, of beauty and transcendence through art,” McLendon comments:

“We tend sometimes to think beauty is easy, and that it’s not part of social engagement. I think, however, beauty can actually be incredibly subversive, particularly in these times. What does it mean to leave the cynical behind for a moment, and focus on beauty? I think that’s a real line that we have to walk. Sometimes, we do it really well. Sometimes, we don’t do it so well. All museums are constantly trying to find what that balance is.

“I think about it a lot.”

Future plans for the McNay Art Museum

The McNay possesses an example of Claude Monet‘s Nympheas (Water Lilies) series.

“It is just sheer beauty,” McLendon says. “You can talk about the revolution that was impressionism. But when our visitors come, they sit in front of it and just have this moment of transcendent beauty. We have to recognise, particularly right now when we are also destabilised at every moment of every day, that this is as important as all of the very important social engagement that we are involved with, with our artists.”

Turning to his plans for the McNay Art Museum in the short and the longer term, he says:

“I’m fortunate that this is an amazing team of museum professionals. So, in the short term, it will be about keeping steady. We have great exhibitions planned. After Dreamland we have a fantastic exhibition coming up with the de la Torre brothers who live both in Mexico and the United States.

“They have an amazing artistic practice. They’re looking at sources as complex as European modernism, indigenous Mexican, and contemporary pop culture on both sides of the border. Because of where San Antonio is located, I think this work will be incredibly poignant and resonant with our audiences. I’m very excited about just continuing to support all that type of work that is currently in place.”

New curator of Latinx art

In the longer term, he adds:

“We have some real opportunities with the Tobin Collection of Theatre Arts. It needs to be better known and better understood: what a truly remarkable resource it is. I look forward to working with the team to think about how to spread the word and activate that collection on a national and international level.

“I’m very excited about that, and very excited, too, that we have just hired a new curator of Latinx art, Mia Lopez.”

The position is funded by four national funding partners, the Alice L. Walton Foundation, Ford Foundation, Mellon Foundation, and Pilot House Philanthropy, through their Leadership in Art Museums (LAM) initiative.

“She will be the first curator of Latinx art at the McNay Art Museum. We have a long history of collecting Latinx art. But this will bring a focus on really engaging those communities, both in San Antonio and wider afield.”

“The third thing that I’m excited about is the opportunity of our outdoor space. We completed the first part of a landscape master plan a few years ago. That greatly enhanced the usage of our 25 acres, but it was just the first step.

“We do a program on the second Thursday of every month, where we open for free later in the evening. We have local musicians and food trucks. People bring their babies and their dogs, and are out on the grounds – it’s fantastic. We get a thousand or more people each time we do one of these. I am currently thinking about how to build on that success and find other ways to engage the outdoor space. It is something very few museums have to offer.”

The McNay Art Museum: a place of belonging

All the plans for the future refer back, he points out, to the museum’s vision statement:

‘The McNay will be San Antonio’s place of belonging, where the Museum’s expanding community is reflected in transformational art experiences’:

“It was one of the things that drew me to this opportunity, says McLendon. “The word ‘belonging’ is so important.

“It permeates everything that we do at the McNay, in a special and important way; the Theatre Arts collection, the contemporary exhibition program, what we’re adding to the collection, the addition of the Latinx curator, how we activate the grounds to help people feel that the museum is their place of belonging, their home in the community.

“We constantly talk about the importance of those third spaces, and think of the museum as a third space. All of that is in service to the mission and the vision of engaging people through art, and then making sure that we are San Antonio’s place of belonging.”