Step into the church of Kehinde Wiley. “An Archaeology of Silence,” on view at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Nov. 19 through May 27, invites viewers to meditate on 22 of the artist’s largest and smallest works in what he describes as a chapel-like environment.

Wiley borrowed the Venetian method of casting light on a body to signify divinity. In “Archaeology of Silence,” the most daunting works are illuminated by a piercing brightness typically reserved Christ, his followers, and by extension, whiteness.

Fitting, as the show made its debut at the 2022 Venice Biennale. It later expanded to 26 works for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco earlier this year before arriving in Houston.

HOUSTON CHRONICLE EXCLUSIVE: U.S. Army announces 3-step plan to restore honor for overturned Camp Logan convictions

Visitors enter MFAH’s iteration by turning a corner into near-darkness. A short circuit of galleries ebb and flow, building into a crescendo of intimacy and scale.

The pairings of paintings and sculptures are in conversation with one another, explains MFAH associate curator of modern and contemporary art Anita Bateman. “He wants people to consider different aspects of commodification in our post-George Floyd world,” she says.

Wiley re-imagines the history of domination and patriarchy by concentrating on the vulnerable, the fallen and the broken instead.

Black youth are inserted into scenes reminiscent of Christian martyrdom, Greek mythology and European art history. Some are recognizable from the Black Lives Matter movement. He “makes corrections” to Civil War-era monuments intended to terrorize or feel irrevocably permanent, too.

Despite the heavy subject matter, Wiley doesn’t take any of it too seriously. He welcomes feelings of both reverence and irreverence. All emotional experiences are valid, including joy.

“My mother is a linguist,” he says. “She’s told me there’s got to be a way to discuss astrophysics and Ebonics.”

Old masters, new style

Most will associate Wiley with his portrait of President Barack Obama, a vibrant and verdant oil on canvas in the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery “America’s Presidents” exhibition. The artist’s calling card is to create highly naturalistic depictions of Black people in the style of Old Masters.

In “An Archaeology of Silence” he melds and remixes the facial features of police brutality victims.

“Dying Gaul, after a Roman Sculpture of the 1st Century” (2021) depicts a hooded figure — and though his face is partially hidden, Wiley immediately references Trayvon Martin. The artist notes that it’s possible to move beyond political context, and simply want to know what he looks like.

“Art becomes a provocation, a Rorschach test,” he says. “Come with openness to poetry and verve. Ask: ‘Who is this person? How did they get here and what is their story?'”

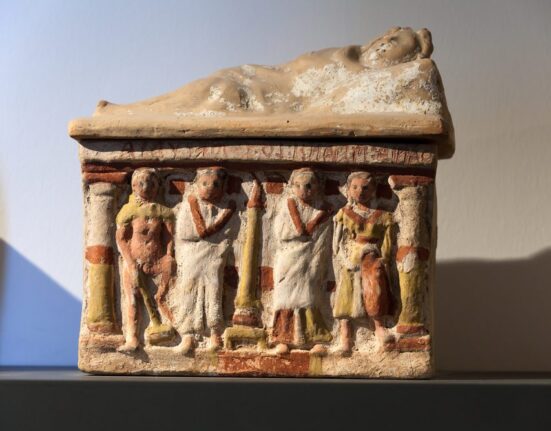

Nearby, smaller bronze sculptures are scaled for the parental gaze. As the father of an 8-year old, Wiley instinctively cradles his arms as he approaches “Entombment, after Titian 1559” (2021) of a Black male in the fetal position.

Two larger sculptures, “The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (Babacar Mane)” (2021) and “The Dead Toreador (Sophie Ndiaye) after Eduoard Manet” (2021), are a direct reference to Hans Holbein the Younger’s “The Dead Christ in the Tomb” (1521-22). Set inside the museum’s walls, Wiley’s rendition makes physical and metaphorical space for the telling of Black stories.

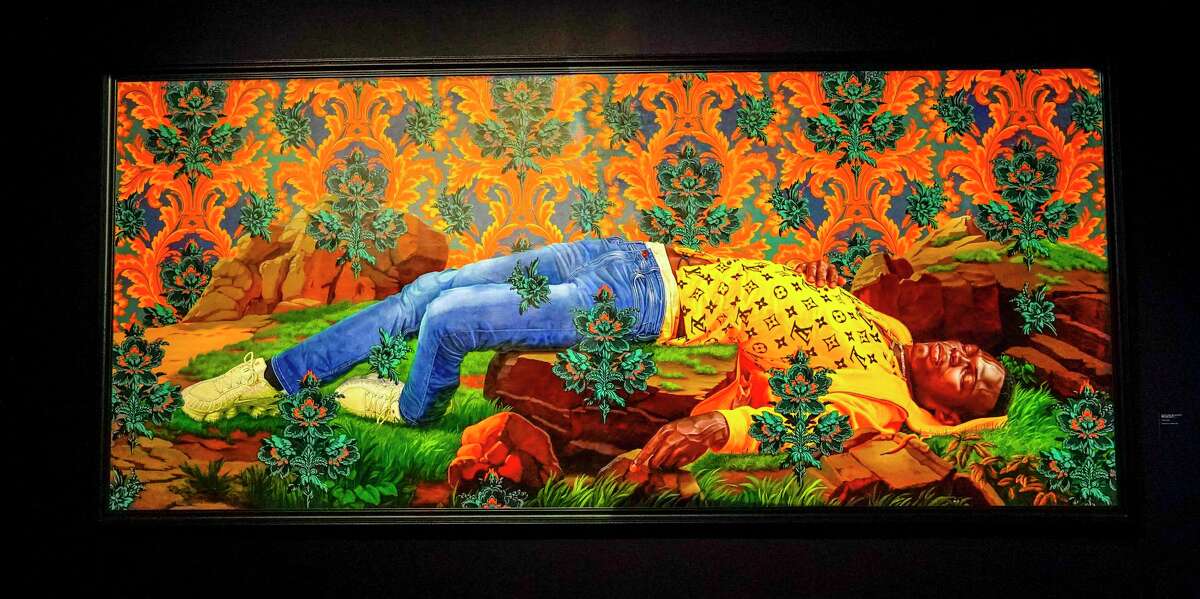

“Femme Piquée par un Serpent” (Mamadou Gueye), 2022, oil on canvas by Kehinde Wiley, the artist behind President Barack Obama’s famous verdant portrait, part of “An Archeology of Silence” at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston on Tuesday, Nov. 14, 2023, in Houston.

Karen Warren/Staff photographerDeeper into the show, “Femme Piquée par un Serpent (Mamadou Gueye)” (2008) tips the scale into monumental proportions. At 25-feet wide, Wiley notes that scope is usually reserved for war or religion settings.

“Here it allows your eyes to enjoy color and texture. Media culture uses it for billboards to sell us things,” he adds. The subject’s marigold, LV-logo hoodie pulls on the commercialization through-line. “Yellow takes up all the oxygen in the room. It grabs you. And material things, real or fake, have taken over West Africa.”

Senegal connection

Wiley conceived of “An Archaeology of Silence” during COVID while quarantining at Black Rock in Senegal, a multi-disciplinary artist-in-residency program, he founded in 2019. There, he didn’t use his usual model street casting; members of his staff and Senegalese artists posed for some of the show’s most substantial works.

“The Virgin Martyr St. Cecilia” (2021), bronze sculpture of a shirtless, lifeless Black male, signifies that bridge.

“His Sengalese bracelet shows the West and Africa coming together in a most American way,” he says. “Even his shoes are of this moment. Everything feels so violently present.”

That work, and the two galleries that follow, are tinged with decay, he adds. They exist between death and the erotic. His hope is to infuse new life into such finality.

Kehinde Wiley looks up at his show’s namesake bronze sculpture “An Archaeology of Silence” at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston on Tuesday, Nov. 14, 2023, in Houston.

Karen Warren/Staff photographerThe exhibition’s namesake sculpture, “An Archaeology of Silence,” (2021) is the most emotionally-charged and provocative piece for the artist. Wiley sent drones to capture 360-degree images of a horse monument in Virginia before recreating its form in his studio. He then created a “fallen hero” to drape across its saddle, replacing the “powerful, white men” typically positioned there, erect and strident.

“Your body is the second cast member in this play,” Wiley says. “I wanted to breathe life into traditional sculpture.”

He insists the show is not about art with a capital “A.” Growing up in South Los Angeles, Wiley says he held art at arm’s length. Deconstructing the Old Masters satisfies his desire to be seen and break centuries of silence.

“This brings a bit of attention to people who look like me,” he says. “We were here, and this our trace.”