Bianca Ruthven, Collections Management Associate, Department of European Paintings

View of a past installation in gallery 624 in the Department of European Paintings

With change comes opportunity, and while the motivation for the European Paintings Skylights Project is practical—to make necessary building repairs—it will also result in long-term benefits for both our visitors and the paintings themselves.

As Keith Christiansen, the John Pope-Hennessy Chairman of the Department of European Paintings, noted in a previous blog post, after the skylights are replaced, visitors will be able to see the masterpieces—literally—in a new light. Until then, we in the department’s collection-care staff, who are tasked with moving these cherished paintings, have an opportunity to see them in a way in which we don’t see them when they are on view: off the gallery wall, unframed, occasionally in an incorrect orientation, and from new angles. New discoveries are being made as we study the backs of paintings, empty frames, and unlikely pairings of paintings on carts, storage racks, and side by side on an exam table.

In moving paintings and frames from storerooms that will be affected by the project to a new storeroom far from the construction activity that will begin this summer, we are presented with the chance to record potential improvements to the artworks. Some need modernized hanging hardware, others need new backing boards to protect the painting from dust and excessive vibration, and all of them are getting dusted.

Animated image of Departmental Technician Garth Swanson dusting a painting’s frame. Image by the author

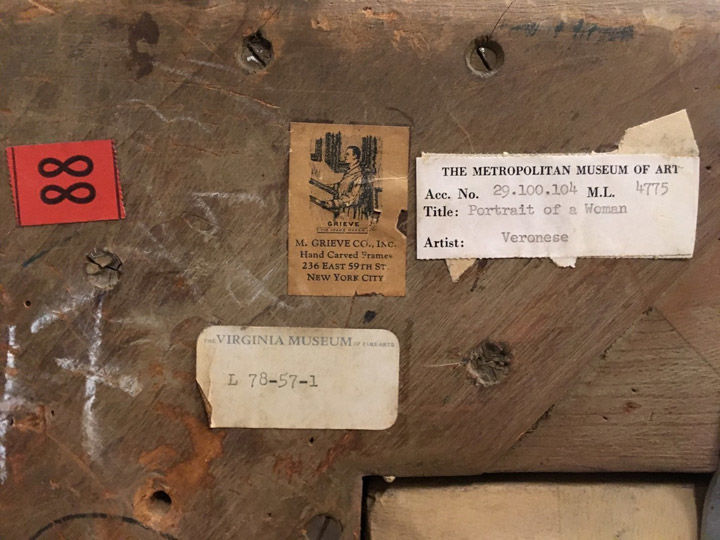

Some of the most interesting things to be seen on a painting or its frame are actually found on the backside, such as old notes, labels, signatures, and more. Here on the back of the frame for Portrait of a Woman by Francesco Montemezzano we see: an old inventory number (88); a label noting that the beautiful frame was worked on by M. Grieve Co., Inc.; a sticker showing that the painting was at one time lent to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; and another sticker from when the picture had been formerly attributed to Veronese. That’s a lot of information packed into just a few square inches!

Photo by the author

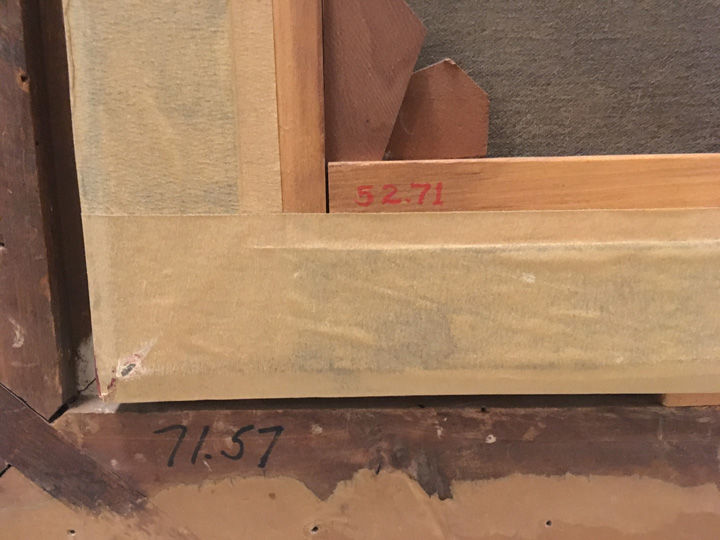

In another instance, we came across a painting that had been reframed. This frame, which had once belonged to Ducks Resting in Sunshine (1753) by Jean-Baptiste Oudry, is currently presented on Study of a Nude Man (ca. 1810–20) by an early 19th-century French painter. We were able to conclude that this frame, now being used in a portrait orientation, must have previously been used in a landscape orientation, which means that its hardware needed to change as the frame needs to be able to handle weight from various points.

Photo by the author

As paintings are transferred to the new storeroom, serendipitous pairings create playful, interesting, and surprising narratives. In the image below, you see George Moore (1852–1933) at the Café (1878 or 1879) by Édouard Manet, and it looks almost as if Moore is looking out a window to a view of The Doge’s Palace Seen from San Giorgio Maggiore (1908) by Claude Monet.

Photo by the author

Not everything is happening behind the scenes though. One thing that you as a visitor may be able to observe, if you are in the right place at the right time, is art in transit. In this image, you see Portrait of a Horseman by James Seymore riding (pun intended) on a cart to its new temporary storage location. Please always remember to yield to art in transit!

Photo by the author

Next, we will begin to deinstall the galleries this spring, at which point we will no doubt make more interesting discoveries. Stay tuned for more project updates!

View the web feature Met Masterpieces in a New Light for more information about the Skylights Project and explore ways to engage with the Department of European Paintings’ collection online.