Afternoon sunbeams stretched across the vast floor inside a palazzo that occupies an entire New York City block. A clock without hands overlooked the empty drill hall, time forever suspended.

It was a rare moment of stillness for the 142-year-old Seventh Regiment Armory on Park Avenue, also known as the Park Avenue Armory. Soon, trucks and workers would rush in to prepare for the next cultural happening in a building that both embraces and belies its Gilded Age beginnings.

The European Fine Art Foundation (TEFAF) fair is setting up camp in the armory for its latest New York edition. From May 12 to 16, the fair will feature 91 galleries covering 7,000 years of art — both in the main hall and in the richly restored period rooms designed by such 19th-century luminaries as Louis Comfort Tiffany, Stanford White and the Herter Brothers.

“The armory is one of the most special places that you can imagine to build, especially because of the history and the fantastic rooms,” said Tom Postma, whose Netherlands-based firm has designed every TEFAF fair. “It’s more or less one of the holy places of New York.”

Apologies to nearby landmarks like St. Patrick’s Cathedral and Central Synagogue, but the armory has always had awe-inspiring ambitions. Consider its wealthy past to understand its eclectic present.

A Social Club for the Rich

The precursor to the National Guard, volunteer militias like the Seventh Regiment were first formed to prepare for foreign, and then domestic, threats. The regiment included so many prominent New York families like the Astors, Roosevelts and Vanderbilts that it was nicknamed the Silk Stockings Regiment. Its members fought in the War of 1812 and were among the first to answer Lincoln’s call in the Civil War.

By the last quarter of the 19th century, the militias were focused on quelling local unrest from labor movements. Armories, with their castle exteriors, were there to protect the status quo. Between 1879 and the outbreak of World War II, 24 armories sprang up in New York City, according to Nancy L. Todd, the author of “New York’s Historic Armories: An Illustrated History.” But their size shielded their secondary purpose.

“The armories were the community social club of the rich and powerful,” Ms. Todd said.

The Seventh was the only privately funded armory in the country, designed by Charles Clinton, architect of the sprawling Apthorp apartments on the Upper West Side. The regiment’s 16 companies each hired top architects to create elegant mahogany man caves with cigar lounges, lockers, libraries and billiard tables. The Board of Officers Room featured Herter Brothers furniture. The Veterans Room showcased Tiffany-designed interiors, including windows and a fireplace mantel that were hallmarks of the American Aesthetic Movement.

The drill hall announced its ambitious intentions from the start. In May 1881, Leopold Damrosch conducted a concert for an audience of 8,000, featuring a 250-person orchestra and 1,700-member chorus.

The wooden floor was painted with tennis lines for recreational players and the national indoor tennis championships that crowned the likes of Bill Tilden, René Lacoste and Hazel Hotchkiss Wightman.

Eleanor Roosevelt attended balls there, and in 1957, the hall was the site of a gala for Queen Elizabeth II.

By 2000, however, the armory had fallen into such disrepair that it landed on a list of the world’s most endangered historic sites. Arts and antiques fairs continued there amid crumbling walls, rats and allegations of mismanagement.

The businessman Wade Thompson, living across the street, was appalled by its condition. He and Elihu Rose, along with Rebecca Robertson, who had redeveloped Lincoln Center, saw its potential as an arts center. They formed the Park Avenue Armory Conservancy, signing a 99-year lease with New York State in 2006. In 2007, the armory began a $215 million renovation, engaging a Swiss firm, Herzog & de Meuron.

Today, the armory is a work in progress serving multiple communities. There is a women’s shelter on its top floors. Artists-in-residence work in semi-restored second-floor rooms.

A storage alcove is stacked with random detritus: an armless Greek warrior, several sets of antlers, a modern wood stool and a bronze bust of a mustachioed Seventh Regiment sergeant.

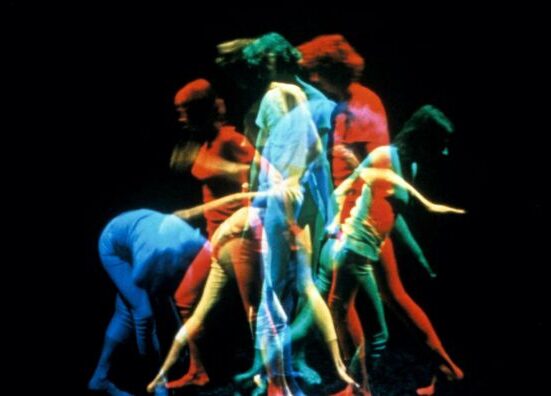

The Wade Thompson Drill Hall has departed from its patrician roots to host such events as a Lenape powwow, a roller-skating rink for Theaster Gates’s Black Artists Retreat and an avant-garde Dutch opera featuring a herd of 100 Pennsylvania sheep. The acoustics bouncing off the 85-foot barrel-vaulted ceiling have remained dynamic, whether for the Berlin Philharmonic or a single piano atop an indoor lake.

“The shape of the room, the way it’s curved, I’ve always felt like they knew that they were going to do some of these things,” said Ms. Robertson, president and executive producer of the Armory Conservancy. “It was in their DNA.”

A Mammoth Task

To build a self-contained art city in six days takes precision, said Mr. Postma, who likens TEFAF’s installation to a “military expedition.” Trucks unload on a choreographed schedule through the Lexington Avenue garage door between 66th and 67th Streets.

Workers lay a wooden floor, then carpeting — gray and pastel pink this year. Then they construct the exhibit booths and cafes — including a champagne bar, a coffee bar, an oyster bar and a salmon bar.

Because the armory is landmarked, renters are prohibited from touching any of the art, walls, floors and furniture in the front rooms.

Dani Mileo, Mr. Postma’s chief designer, said that since 2016 they had shifted from translucent screens to white wall coverings. “It’s a question of what you conceal, what you reveal and how much you allow to come through at different moments,” she said.

That layering of ancient and modern is perfect for antiquities dealers like Gladys Chenel. Her Paris gallery was assigned the second floor Company D room this year, with its carved mahogany and trompe l’oeil ceiling.

Elaborate floral designs have been a fixture of TEFAF. Because the fair is a week later this spring, its signature Dutch tulips will be out of season. Bastiaan Hutten of Ten Kate Flowers and Decorations in the Netherlands imported white and pink orchids from Thailand. Some of his 20,000 cut stems will hang in 13-foot-long columns from a bar suspended from the ceiling.

In the last couple of years, lighting has become more critical to the fair’s designers, thanks to social media. The colors of the art, and the fabric-covered gallery walls, must reflect well off different skin tones. “If people can’t snap a nice picture, they won’t, and it won’t get out there,” Ms. Mileo said.

Sean Kelly, a gallery owner, is amazed how the cavernous space becomes an intimate experience. This year, his booth displays three artists around a theme in sync with the armory: time. One artist, Joseph Kosuth, places clocks with hands running at different speeds alongside existential quotes from philosophers in neon.

Mr. Kelly says it is a privilege to play in a place he calls a palimpsest.

“You have the building, you have New York City, you have the history of the building,” he said, “and then we can go in for a short period of time and create a new story, a new history.”