There are stories within stories folded into the 46 paintings and works on paper at Museum of Fine Arts, Houston where “Rembrandt to Van Gogh: Masterpieces From the Armand Hammer Collection” is currently on view through Jan. 21, 2024.

Yes, that Armand Hammer —- the late great-grandfather of actor Armie Hammer and founder of the Hammer Museum at University of California, Los Angeles. A quick Google search will unspool the Hammer family’s complicated history, though that thread manages to somehow play second fiddle to the captivating survey of European and American art displayed on the second level of the Caroline Wiess Law Building. Many of the works are rarely seen outside Los Angeles.

HOUSTONCHRONICLE.COM: McWilliams Dog Park officially open in Hermann Park, with water features and dog wash station

“Rembrandt to Van Gogh” is representative of the finest Hammer Museum Holdings has to offer, suggests Helga Aurisch, MFAH curator of European art who co-curated the exhibition with Ann Dumas. Armand Hammer, a businessman best known as longtime president and CEO of Occidental Petroleum, collected art across four centuries; big draws of the show include 16th-century Old Masters.

This is a carousel. Use Next and Previous buttons to navigate

Visitors are greeted by Rembrandt van Rijn’s commanding “Juno” (circa 1662-65). In mythology, she was the wife of Jupiter, king of the gods. In Rembrandt’s orbit, the subject’s likeness is rumored to have been the artist’s second wife by common law.

“She was queen of the heavens and shown in Rembrandt’s world as a baroque queen,” Aurisch says. “He made up an incredible outfit (for her) and a domineering pose that’s quite confrontational. There’s a peacock in the lower left and he kept a left arm change (in) for movement.”

This is Rembrandt at his very best, she added, noting his mastery of paint and shadows at this point in his career. He died soon after its completion in 1669.

Along an adjacent wall is “Woman at her Dressing Table” (circa 1645) by one of Rembrandt’s favorite pupils, Ferdinand Bol. “The sitter may be Rembrandt’s first wife,” Aurisch says. “So we may have both of his ladies here.”

Nearby is Peter Paul Rubens’ “Young Woman with Curly Hair” (circa 1618-20.) Flaxen tendrils and the paintings’ overall fluidity exemplify why Rubens is regarded as one of the greatest portrait artists. “Portrait of a Man in Armor” (circa 1530) by Tiziano “Titian” Vecellio is the exhibition’s oldest work. Here, the eye is drawn to highlights glinting in the Renaissance knight’s armor and his self-contained, quietly confident pose — the markings of true nobility.

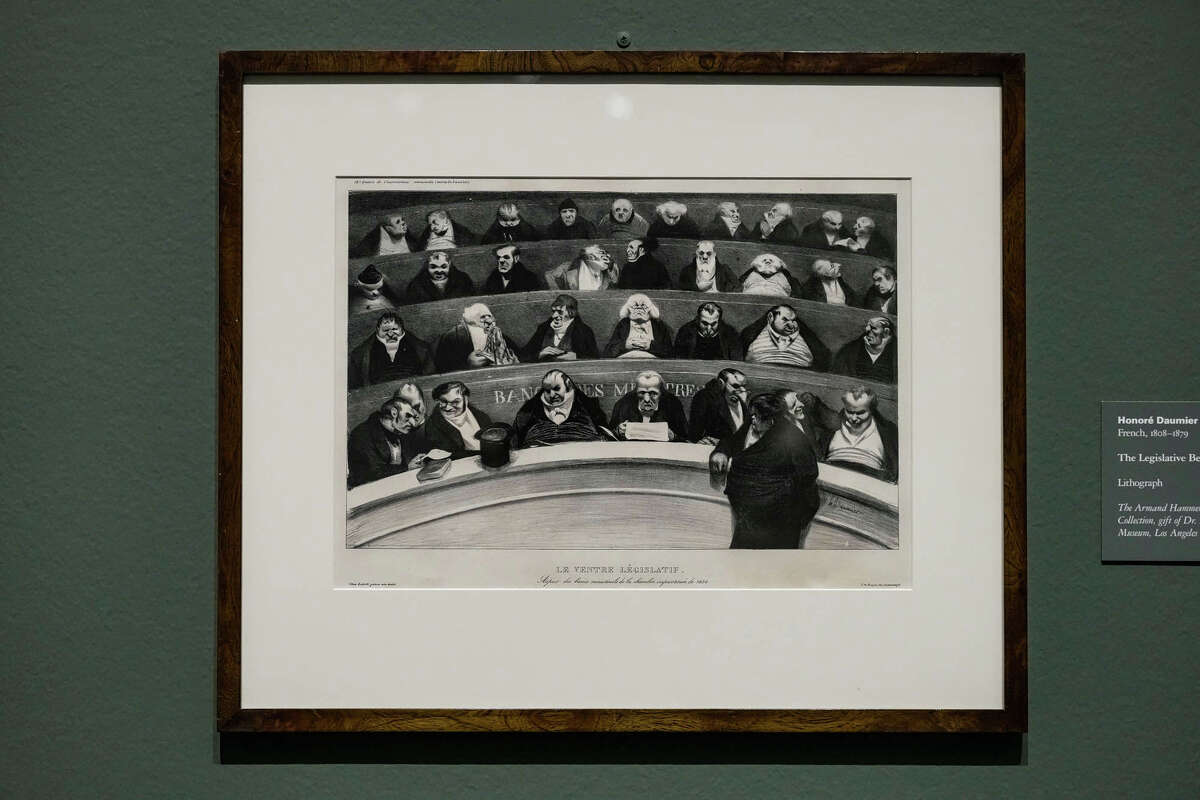

Across the way, Honoré Daumier shifts the narrative into political territory, beginning with a series of clever lithographs. Unfortunately, not all French aristocracy shared his sense of humor. “The Past, the Present, the Future” (1834) satirizing King Louis-Philippe landed the artist in jail for months. “The Legislative Belly” (1834) depicts lawmakers in various states of disengagement, from visibly bored to asleep. “They were much worse than Congress today,” Aurisch quips.

She has a favorite bronze sculpture in Daumier’s “Caricature Busts of the Célébrités du Juste Milieu” and encourages onlookers to select one, too. A look at his lithographs, “How to Use the Petticoats” (1856) and “Rue Transnonian” (1834), and oil on canvas painting “The Lawyers” (1860) point to how Daumier inspired the French Impressionist Edgar Degas and “catching people when they’re unaware,” notes Gary Tinterow, MFAH director and Margaret Alkek Williams Chair.

With two neighboring paintings by Gustave Moreau, “King David” (1878) and “Salomé Dancing Before Herod” (1876), Degas took a different stance.

“They were travel buddies until these paintings,” Tinterow says. “Then (Degas) dismissively referred to Moreau as a goldsmith.”

Their drama aside, Tinterow credits a number of early-20th-century colorists to Moreau and his ability to exercise color theory where emphasis should be.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot closes the loop on early-19th-century French practices with “Morning” (1865.) Inside the silvery idyll with dancing flecks of paint and pops of red, landscape becomes more prominent than its figures: a young woman playing with three cherubs in the style of Homer’s “rosy-figured dawn.”

For his influence, contemporaries dubbed the artist “Père (or Papa) Corot.” “Though Corot considered himself an Old Master,” Tinterow says.

When: through Jan. 21, 2024

Where: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1001 Bissonnet

Details: All-access tickets, $20 and up; 713-639-7300 mfah.org

The next gallery, “Realism and Impression,” delves into the second half of the 19th century and new trends in French art. If Corot picked up the baton for more realistic styles, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley took off running.

Alfred Stevens, considered the preeminent society painter of his day, captured the actress and well-known eccentric Sarah Bernhardt thousands of times; she first gain notoriety after becoming the first woman to portray “Hamlet.” “Portrait of Sarah Bernhardt” (1885) depicts her as elegant, if not a touch unruly. She’s back-lit, dressed in rarely seen black, and with a posy of flower tucked into her décolletage.

Jean-Francois Millet’s “Peasants Resting” (1866) further explores the notion of “real people,” romanticizing the working class and rural life as the Industrial Revolution spread across mid-19th-century France in this instance. “He gave them dignity and elevated the labored class to a level working people never enjoyed in paintings,” Tinterow says.

HOUSTONCHRONICLE.COM: Four Tony winners, including Taylor Swift’s Speak Now tour designer, receive Alley Theatre awards

A trio of Henri Fantin-Latour paintings share a parallel wall, including “Peonies in a Blue and White Vase” (1872). Aurisch describes his portrayals as “sensitive” and somewhat unappreciated at the time, as they were deemed too simple, assuming and realistic for the French. “He looked at flowers first as a botanist as opposed to pushing them into triangles, shapes or particular color schemes,” she says.

Within a yellow-walled enclave visitors arrive at the Armand Hammer pièce de résistance, Vincent van Gogh’s “Hospital at Saint-Rémy” (1889) from the penultimate year of his life. The serene scene of his resident asylum in the South of France is also one of his most iconic. His expressive strokes appear almost three-dimensional. And with swirls of yellow, his happy color.

Claude Monet’s “View of Bordighera” (1884) highlights another coastal village, this one in southern Italy. Then, marvel at the revelry and streamers in the center of Paris from Camille Pissarro’s “Boulvard Montmarte, Mardi Gras” (1897) before taking pause at “Boy Resting” (circa 1887) by Paul Cezanne, near the artist’s hometown, Aix-en-Provence. The young man is likely the Cezanne’s son.

It’s one of Tinterow’s favorites. He draws attention to the thousands of minute perceptions that feel inevitable, the culmination of many months.

“Picasso and Matisse both said that Cezanne is the father of us all,” Tinterow remarks. “He wasn’t fashionable, or slave to reality, and became an early modernist.”

Aurisch agrees with Cezanne’s ability to create an alternate reality. “Rembrandt to Van Gogh” feels a bit like that, too. “Masterpieces From the Armand Hammer Collection” invites an internal dialogue about the subjects, both real and imagined, the artists who immortalized them; and the man who spent a better part of his life amassing their works.