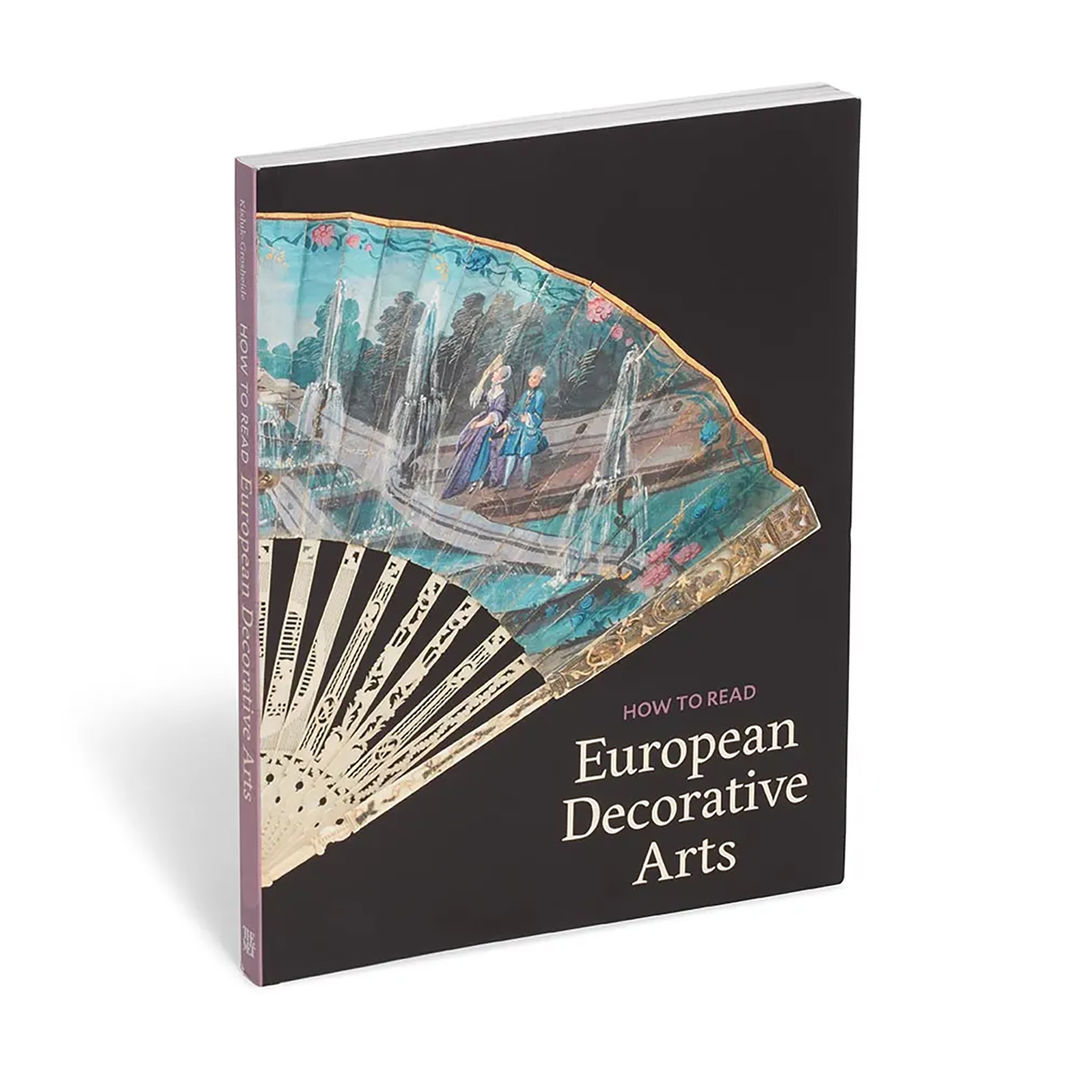

How to Read European Decorative Arts, the latest volume in The Met’s How to Read series, illuminates European artistry and ingenuity in decorative arts from the High Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution through forty exemplary objects.

I spoke with curator and author Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide about the categorization of fine and decorative arts, the role of anonymous female artisans in European workshops, and what eighteenth-century artists might think of today’s Marie Kondo minimalism.

The cover of How to Read European Decorative Arts

Delia Cruz Kelly:

From the outset, How to Read European Decorative Arts reexamines the value of the field by interrogating perceptions of these works as “merely decorative.” Instead, you position decorative arts as holding equal importance as fine arts. To begin, can you distinguish the decorative arts from the fine arts and speak to the ways your scholarship has questioned the hierarchy of these categories?

Daniëlle Kisluk-Grosheide:

There is still a clear distinction felt between the decorative arts and the fine arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture. That difference came into being during the Renaissance when people began characterizing the fine arts as having to do with the creative process, which elevated these art forms above the mechanical arts (as the decorative arts were also called). Decorative arts, made by craftspeople, resulted in more utilitarian objects that could also be ornamental. I was thinking about that distinction when writing this book.

I’ve worked as a curator of decorative arts all my life, and sometimes it feels like we are the props department. Sometimes we are asked: “Do you have an object similar to what is depicted in this painting?” I think the decorative arts deserve a second consideration. Why is a figurine in porcelain called a piece of decorative art whereas a statue of clay or marble is called sculpture? Sometimes the same artists worked on both types of objects.

Very often the designs of decorative arts were borrowed from the compositions of or specifically created by fine artists—sculptors, draftsmen, and painters. There is not always such a clear distinction. The fields very often overlap, and that’s what I wanted to raise in the introduction of the book. The publication accompanies a small installation in Gallery 521, on view through August 2024, and I hope that both will help visitors reevaluate the placement of the decorative arts. Why is a painted scene not considered a painting when it is rendered on a fan or a piece of porcelain?

Folding Fan, French (Paris), ca. 1783, Painted paper; ivory, partly silvered and gilded; strass rivet, 10 ½ x 18 ¾ in. (26.7 x 47.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Henry J. Bernheim, 1959 (59.13.7)

Cruz Kelly:

You’re speaking to a standard of mastery that we see in both the fine arts and decorative arts. This book considers the contributions of a few renowned masters, such as the Dutch cabinetmaker Jan van Mekeren and the Italian goldsmith Andrea Boucheron, but some of the most stunning objects, like the gorgeous, embroidered chest with scenes from the Story of Esther, or the soft-paste porcelain flowers manufactured in Vincennes, just east of Paris, are lesser-known and unattributed. Whether objects are produced in a workshop or privately at home, artisan anonymity—especially that of female creators—seems more common in the decorative arts. What does our limited understanding of where and from whom these objects come from tell us about the role of the maker in European decorative arts?

Left: Casket with Scenes from the Story of Esther, British, after 1665, Wood; silk satin worked with silk and metal thread; seed pearls, mica, and feathers; metal-thread trim; wood frame; silk lining; mirror glass, glass bottles; printed paper, 9 ¼ x 16 x 11 ¼ in. (23.5 x 40.6 x 28.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964 (64.101.1335). Right: Flowers, French (probably Vincennes) mid-18th century, Soft-paste porcelain, (largest) 1 ¼ x 2 15/16 x 2 ¾ in. (3.2 x 7.5 x 7 cm), (smallest) 1 x 1 ½ x 1 ½ (2.5 x 3.8 x 3.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 2019 (2019.283.56-58, 60-61)

Kisluk-Grosheide:

There are many works in the decorative arts for which we do not know the name of the maker; in fact, there are probably more unattributed works than those that are signed and dated.

As you noted, for many works such as the fan on the cover of the book and the flowers most likely made at the Vincennes manufactory, we don’t know the makers’ names and that could be because they were women. Women were not usually members of the guild. Their names were not recorded. Yet, the daughters and wives of masters in certain workshops probably made up about half of the workforce.

It’s only in rare circumstances that we have evidence of women’s contributions. We have an enamel casket by Susanne de Court; she was a sixteenth-century artist working in Limoges, France. She quite often initialed her works or signed her name full-out and yet we know very little about her, but her signature is evidence that there women active in this field.

Left: Casket, Susanne (de) Court (French, active ca. 1575–1625), French (Limoges), early 17th century, Enamel painted on copper; gilded-silver frame, 7 ¾ x 9 ½ x 5 ¼ in. (19.7 x 24.1 x 13.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. And Mrs. Walter Mendelsohn, 1980 (1980.203.2). Right: Detail of casket showing de Court’s name

Makers often didn’t identify themselves, although occasionally they did. There is this amazing silver ewer included in the book by Adam van Vianen, a goldsmith. Rather than stamping the silver with his master’s mark, he signed and dated it as an artist would sign and date a work of art. Again, there’s that crossover between the fine and decorative arts: it seems Van Vianen identified more as a sculptor—a sculptor in silver—than as a goldsmith or silversmith. I love examples like this.

Left: Ewer with Scenes from the Legend of Marcus Curtius, Adam van Vianen (Dutch, 1568/69-1627), Dutch (Utrecht), 1619, Silver, 9 1/16 x 5 x 4 ¾ in. (23 x 12.7 x 12.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace and Howard S. and Nancy Marks Gifts; Gift of Irwin Untermyer and funds from various donors, by exchange; From the Marion E. and Leonard A. Cohn Collection, Bequest of Marion E. Cohn, by exchange; Bequest of Bernard M. Baruch and Gift of Robert M. Hillas, by exchange; Bequest of John L. Cadwalader and Gifts of Lewis Einstein and William H. Weintraub, by exchange; From the Collection of Mrs. Lathrop Colgate Harper, Bequest of Mabel Herbert Harper and Bequest of Alexandrine Sinsheimer, by exchange, 2018 (2018.194a, b). Right: Detail of the silver ewer.

Cruz Kelly:

This book’s incredible variety of objects, materials, technologies, geographic origins, and time periods is rarely seen together in one publication—essentially, these forty objects represent three centuries of European history. Can you tell me about your selection process and the opportunities this collection affords to both new students and experienced collectors of decorative arts?

Kisluk-Grosheide:

The selection was difficult! We hold about sixty thousand objects in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, and I was trying to be as complete as possible and find representative objects from different parts of Europe. Our holdings are stronger in English, French, Italian, and German than in Scandinavian or Spanish art, but I tried to find objects from different periods and different geographical locations that modeled different techniques, while also being mindful of certain stories I wanted to tell regarding women artists and colonial histories. These are difficult histories to tell, but I felt they were important to include.

Intentionally, I have not chosen some of our most famous pieces. For example, Marie Antoinette’s black lacquer furniture has been written about so often, by others and also by me. Frankly, I thought I had said what I could say about it. Let’s find something else. I combed the online collection; I went through the galleries and to the storeroom. I was looking for specific types of objects and different kind of pieces, but I could’ve chosen forty other ones. Some artworks are new acquisitions, others just spoke to me, and some pieces had interesting stories that made me want to learn more. It is by no means a full history of the decorative arts, but this selection points out different techniques, materials, and narratives that hopefully will be of interest to the reader.

I think this book is a bit like a cookbook of forty chapters: you don’t have to read it from beginning to the end. When you leaf through a cookbook you see a beautiful illustration and think, hat looks delicious. Let’s read this, and maybe, I can make that!” In this case it’s, “Oh! That looks like an interesting object. What is it? How was it used, or how was it created?” That’s what I hope this book will do: inspire people to look at the decorative arts and take an interest. All of us, even if we feel we have no knowledge of the decorative arts, are surrounded by objects daily. Everything we use today was made by someone, designed by someone, and that was also true hundreds of years ago.

Cruz Kelly:

While reading, I was struck with a real sense of amusement in objects like the kitschy porcelain figurine, The Kiss (ca. 1745). The figurine shows a couple locked in embrace and seems to serve no other purpose but enjoyment. We live in a world of Marie Kondo minimalism where we’re all looking at our belongings and asking, “Does it spark joy?” Do you think Europeans of the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries were asking themselves the same question? What can you say about the influence of aesthetics on the production of objects for display and entertainment?

The Kiss, ca. 1745. Modeled by Johann Joachim Kändler (German, 1706–75) After an engraving by Laurent Cars (French, 1699–1771) After a composition by François Boucher (French, 1703-1770) German (Meissen), ca. 1745, Hard-paste porcelain, 8 x 10 1/8 x 6 in. (20.3 x 25.7 x 15.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964 (64.101.58)

Kisluk-Grosheide:

That’s a good question! I think art has always given joy, certainly to their owners and collectors. Why would you collect if not for the pleasure of looking at the work of art? With the decorative arts, the joy of an object is not only about looking but also about handling it: feeling its weight, touching the surface, bringing it closer to the eye, sometimes perceiving the scent that is emanated by certain pieces. That’s the wonderful thing about the decorative arts; these objects have always engaged various senses and sparked joy and pleasure in different ways.

I don’t know exactly when the Marie Kondo minimalism came into being, certainly not in the eighteenth century! Still, I think we marvel at how things were made in the same way someone in the eighteenth century might have. “Look at this perfect piece of porcelain!” I think the response today is the same as when these objects were new, hundreds of years earlier.

“These pieces were also, at times, status symbols just like over-the-top Rolex watches are today.”

These pieces were also, at times, status symbols just like over-the-top Rolex watches are today. Nobody needs a watch now, because every gadget we use—our computers, phones, and microwaves—tell time, yet people still want the Rolex. It was no different for Europeans in the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries.

The longer I study decorative arts, the more I’m convinced that we as human beings haven’t changed. The decorative arts still give us pleasure. They enrich our lives, and they are lovely objects to show off and share with friends.