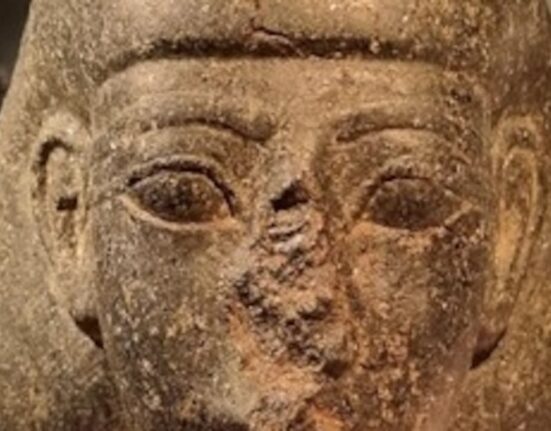

The European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht is a one-stop shop for treasures from the past. Under its vast roof, you can find Greek pots and Egyptian statuettes, Dutch genre paintings and French commodes. For much of its 35-year history, however, it has not been the go-to place for contemporary art.

Now, contemporary galleries are increasingly setting up stands at TEFAF Maastricht. One surprise newcomer this year is White Cube, an international gallery headquartered in London. Founded by Jay Jopling, it represents artists including Anselm Kiefer, Bruce Nauman, Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst and Theaster Gates.

Why choose to show there?

“At Maastricht, you have a selection of the best dealers in the world in every single area,” said Mathieu Paris, senior director of White Cube. “For a gallery like us, where one of the goals is to make the contemporary historic and the historic contemporary, it actually makes sense to build bridges.”

Mr. Paris noted that White Cube had shown four times at TEFAF New York — the satellite fair started at the Park Avenue Armory in 2016. So the decision was made to exhibit on the fair’s home turf in the Netherlands.

Asked how that made commercial sense for White Cube, Mr. Paris said that major Dutch, French, Italian, German and Belgian collectors attended the fair each year, and that they “love mixing, creating bridges, links between objects in their collection.”

On its inaugural Maastricht stand, White Cube is showing a black pixelated sculpture of a body by the British artist Antony Gormley, previously shown in the ancient ruins of Delos in Greece, and priced at about 500,000 pounds ($610,000). Other displays include two works by Georg Baselitz: a black-and-white painting of a figure (€1.2 million or $1.26 million) and a bronze hand-painted sculpture of a leg ($1.3 million).

Bringing together the old and the new “benefits everyone,” said Martine d’Anglejan-Chatillon, an independent producer of contemporary art projects who previously co-founded the Thomas Dane Gallery in London. She said it gave historical galleries as well as contemporary art galleries “something else to chew on.”

In the past, Ms. d’Anglejan-Chatillon explained, the contemporary art world was “very impermeable to a lot of other possibilities,” because it had plenty to sell. Today, the “hyper-obsession with younger artists” has created a sense of “saturation,” and a move toward “a kind of plurality.”

There were also commercial imperatives, she noted. Contemporary art dealers were always looking for the next big thing and eager to cultivate a new clientele. Meanwhile, TEFAF was looking to rejuvenate its profile, because for a long time, it was “a fair about historical works and objects made by long-dead people.”

TEFAF has indeed been striving to modernize its image over the last decade. In 2013, the fair announced that it was teaming up with Sotheby’s and with China’s state-owned Gehua Group to start a satellite fair in Beijing. Nine months later, the project was called off.

Instead, TEFAF inaugurated its New York satellite in October 2016, concentrating on galleries of older art, then held another edition in May 2017 focused on modern and contemporary art. It was an opportunity for the fair to reach out to U.S. collectors.

In the meantime, the board of TEFAF started consulting younger dealers and specialists familiar with the contemporary scene.

One such dealer was Hidde van Seggelen, who heads up his eponymous gallery and now leads TEFAF’s executive committee. His gallery is part of the Modern section at Maastricht, which this year includes more than 40 galleries, mostly European ones, out of a total of 243 across the fair.

Mr. van Seggelen recalled telling the TEFAF board, long before his appointment, to “look at the context in which we operate, and at contemporary and modern art: The market has grown so enormously.”

He noted that TEFAF Maastricht had in recent years put on a number of contemporary art exhibitions to make the link between the old and the new. In 2015, “Night Fishing,” an exhibition of modern and contemporary art curated by Sydney Picasso, showed works by artists such as Mr. Baselitz, Nam June Paik and Tony Cragg, whose dealers had never shown at TEFAF before.

In 2017, a special section curated by Penelope Curtis — then director of the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon and former director of Tate Britain — showed works from different periods in art history, including contemporary ones.

Mr. van Seggelen said that TEFAF’s presence in New York had helped lure galleries of newer art to Maastricht.

The Dutch fair appeals to contemporary art galleries because “you will find collectors that are not part of the contemporary circuit,” he said. “It’s a different world. It may be more quiet, but it’s incredibly powerful, because it’s a completely different context.”

One return exhibitor at TEFAF Maastricht this year is Galleria Continua, a contemporary art gallery based in the hilltop town of San Gimignano in Italy.

It first showed at the fair two years ago. The gallery was born in 1990 as a showcase for contemporary art in Tuscany, a region known predominantly for its extraordinary Renaissance heritage.

“It was a wonderful experience for us to participate in 2020, so we decided to go back,” said Verusca Piazzesi, the gallery’s director, noting that both the media coverage and the sales had been good.

“Showing art in Tuscany means being in a constant confrontation with the past,” she added. “So I’m very pleased to exhibit at Maastricht.”

“The kind of crowd that Maastricht attracts is different from the contemporary art crowd,” she said. “These are truly international collectors with very fine taste who are interested in everything from illuminated manuscripts to contemporary art.”

Ms. Piazzesi said the 2020 booth was dedicated entirely to Mr. Gormley, the British sculptor. This year’s booth will show works by him, Ai Weiwei and Anish Kapoor.

Ms. d’Anglejan-Chatillon said the increasing appeal of Maastricht was “a reflection of our time.”

“People need more meaning, somehow,” she said.