Once a year, The European Fine Art Fair turns Maastricht, a small Dutch university town on the border of Belgium, into an art market cyclotron where highly enriched particles of global wealth are discharged into a powerful magnetic field of refined and concentrated world culture in hopes of achieving fusion.

Perhaps a sign of straitened times, TEFAF’s 37th run this year has been condensed from 10 days to a week. Not that this matters much since the serious buying tends to be done on the VIP-only preview and opening days, and opening day was the busiest it’s ever been, according to the fair’s organisers.

Possibly another sign of difficult times, the VIP crowd seemed more homogeneous than has been the case in previous years – less Russian to be heard in the aisles, fewer Chinese buyers, and an apparently narrower age range. With older generations of private collectors increasingly withdrawing to the sidelines and the younger generations primarily focused on contemporary art, institutional curators – mid-life professionals — are sensing a buying opportunity for museum-grade fine art and antiquities, according to some TEFAF insiders.

With about 260 galleries from 20 countries showing the finest, most carefully sourced and strictly vetted gleanings from 7,000 years of global creativity, there’s plenty to attract their attention – and that’s leaving aside the other-worldly flower arrangements, the oysters and the free-flowing VIP-day champagne.

A few takeaways:

Kicking back against gender inequalities in the art world, a focus on female artists: To mention just a few star pieces, Artemisia Gentileschi’s Penitent Magdalene, c.1626, with a price tag of $ 7 million at Robilant +Voena; an Eileen Gray Japanese-inspired lacquer box for €500,000 at Galerie Chastel Maréchal; and a sculpture by Germaine Richier on the stand of Axel Vervoordt.

In keeping with the vogue for mix-n-match cross collecting, there is a growing presence of modern and contemporary, now close to 50-50, in what was once largely a reserve of the old masters and classical antiquities.

The old guard remains—think Landau Fine Art, Richard Green, Steinitz (with a show-stopping mise-en-scene starring two red lacquer and gilded bronze pagoda-decorated commodes, c. 1750, from the Paris mansion of the Dukes de la Rochefoucauld—Doudeauville). Among the gems are Vincent Van Gogh’s Tête de Paysanne à la coiffe blanche, sold by M.S.Rau for a reported $5 million, and a Van Dyck portrait of a Carmelite Monk at Dickinson.

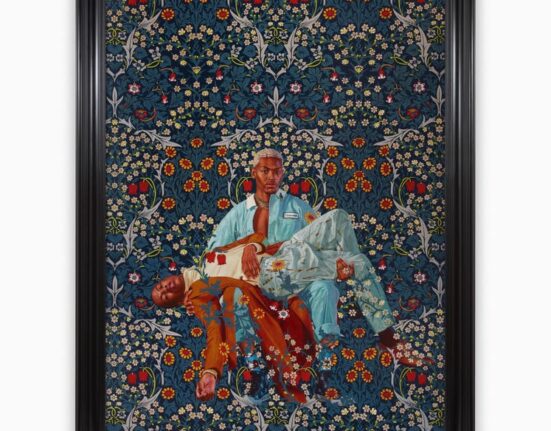

But the contemporary and modern end of the market is now strongly represented, with the likes of White Cube, Galeria Continua, Kamel Mennour, Sean Kelly, and David Gill (a first-timer) hoping to attract a new clientele. Axel Vervoordt, a Tefaf veteran, this year is showing Anish Kapoor, Corbusier, and Ryuji Tanaka alongside Richier.

Alongside these established names, the fair makes space for new players from off the beaten track. Olszewski/Ciacek, focused on Central European avant-garde movements and mid-20th-century avant-garde Poland, is TEFAF’s first Polish exhibitor and winner of the fair’s new Showcase prize.

In hard times, Haute Joaillerie is still a girl’s best friend, but styles have turned more sober, with a preference for high-carat, high-quality gems over fancy settings. This trend plays to the strengths of Munich-based jewellery house Hemmerle, whose taste for coloured cabochons set in materials more mundane than Mondaine is on show in its latest collection.

Words/Top Photo: Tornabuoni Gallery By Claudia Barbieri