In the Seongdong neighborhood of hipster bars and pedestrian streets crowded with the well heeled, the Page Gallery has made a name for itself in a neighborhood where it’s hard to get noticed.

And as the gallery seeks to branch out beyond Seoul, it will attend TEFAF Maastricht, the European Fine Art Foundation’s annual March fair, taking the works of six South Korean artists. Since this will be Page Gallery’s first major art fair outside of Asia, gallery executives see this event as a bit of a launchpad for itself and its roster of artists, many of them Korean.

“We are trying to give some fresh air to the younger artists, and we were accepted this year at TEFAF Maastricht after applying a few times,” said Andy Ilwoo Huh, 31, associate director of the Page Gallery, during a recent tour on a freezing Seoul afternoon. “We are very much looking for the reaction of the conservative European collectors. We are expanding our program and activities around the globe, so TEFAF is one of our first steps.”

That approach is about capitalizing on the current global visibility of the arts in South Korea in the last few years, Mr. Ilwoo Huh said, and in some ways about educating global collectors about the versatility of Korean art. The country’s art is rooted in the volatile history of the Korean War and the decades after, but it’s also about new generations of artists who want to make a name for themselves outside South Korea, he said.

With this in mind, the Page Gallery, founded in 2011, is taking a collection of artists to TEFAF Maastricht that the gallery feels represents the history — and future — of South Korean art. The gallery is in Galleria Forêt, or the Seoul Forest as it’s called locally, an exclusive 45-story apartment building with interiors designed by the French architect Jean Nouvel, an example of old-meets-new in one of Seoul’s most trendy neighborhoods.

“We are focusing on how Korean contemporary arts flow from one of the oldest artists, part of the Dansaekhwa movement, up until artists born in 1969,” Mr. Ilwoo Huh said. “Dansaekhwa artists were the teachers of many of today’s artists, so there’s a sort of cause and effect in Korean art history.” (The country’s Dansaekhwa movement is defined by its monochrome abstract paintings.)

One of the artists whose work will go to Maastricht is Chong Gon Byun, 75. The gallery just finished a solo exhibition of his work in February and will take four of his pieces to Maastricht.

Mr. Byun fled South Korea in 1981 fearing that he would be jailed by the military dictatorship at the time over his provocative political artwork. He went to New York on a student visa (and eventually gained U.S. citizenship) but was invited back to South Korea just before the 1988 Olympics. He has freely traveled to the country since.

“When I came to New York I couldn’t believe how much freedom people had, and the things that people throw out are interesting to me,” Mr. Byun said. “It’s almost like an expression of having too much freedom. There is so much here, but in South Korea in my youth we had nothing to throw out.”

This concept plays into much of Mr. Byun’s work. His recent show was a smorgasbord of mechanical objects, portraits and metal objects. One piece from the exhibition that will travel to Maastricht is “Last Supper” (2011). Like many of his works, it’s a discarded object made new again.

“I found the plaster sculpture of the Last Supper at a flea market in New York, and I spray-painted all of it white, but I kept Jesus in the original color of beige and orange,” said Mr. Byun, who considers himself a Christian. “I also wanted to protect him, so I gave him a helmet that probably came from a doll. He is also holding a piece from a scale. He controls his world.”

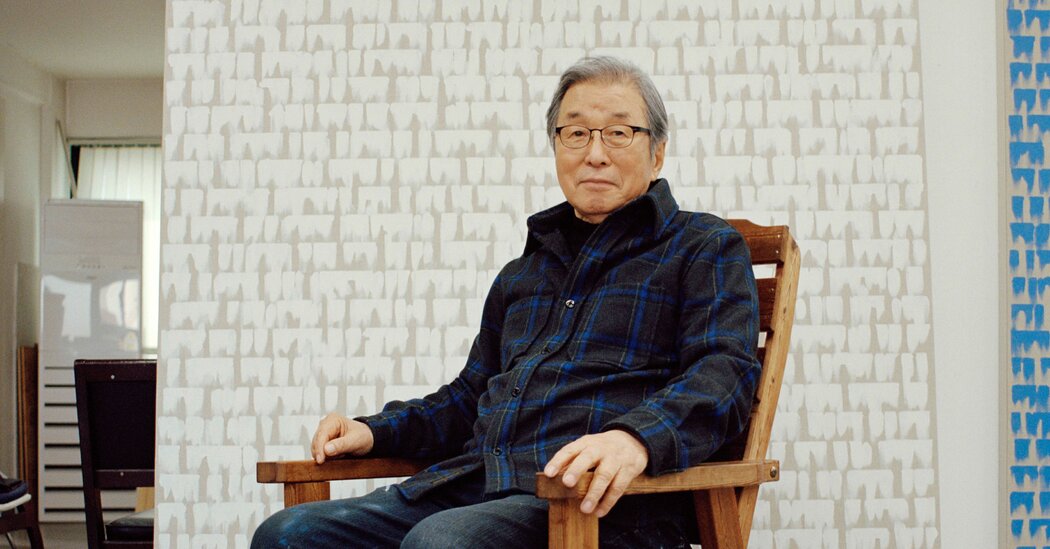

Freedom — and a childhood in a very different South Korea than today — is also a concept that plays into the works of Choi Myoung Young, 82, who defected from North Korea to South Korea as a boy during the Korean War. Mr. Choi, who was educated at Hongik University, was also part of the Korean Avant-Garde Association in the 1970s.

“Choi Myoung Young is a key character in the Dansaekhwa movement, but he is very quiet and always works by himself and doesn’t really care about art sales,” Mr. Ilwoo Huh said. “I think his style, like many of the Dansaekhwa artists, came from their childhoods during the war. There was nothing for young kids to play with, so they played with things in nature like stones, earth, mud and sand.”

This is reflected in much of Mr. Choi’s minimalist patterned works. His works at Maastricht will be part of his “Conditional Planes” series that started in the 1970s, which focus on the elegant minimalism so connected to Dansaekhwa. The Page Gallery also will feature Mr. Choi’s works exclusively at TEFAF New York in May.

“After the Korean War, the restoration of tradition and the modernization of Korean society triggered artists to strive for something new,” Mr. Choi said by email (he doesn’t leave the house much because of his advanced age). “I am part of a commitment by artists to the theory of reduction and expansion that originates from the four seasons, the Korean view of nature, Eastern philosophy and the discipline of Confucianism that embodies a minimalistic lifestyle and philosophy.”

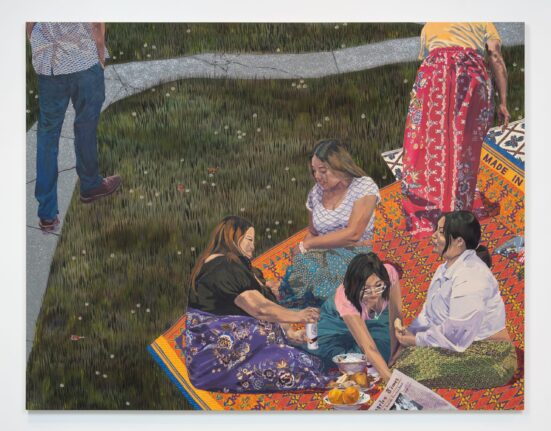

The other four artists whose work will be featured in Maastricht are Yeesookyung, who spells her Korean name without spaces or hyphens and is a performance artist turned sculptor; Jeomsoo Na, who works mostly in abstract sculptures; Park Suk Won, whose minimalist sculptures were featured in an exhibition at the Page Gallery that ended recently; and Suejin Chung, who will also have a solo exhibition at the Page Gallery from August to October during the Frieze Seoul art fair.

Three of Ms. Chung’s pieces will travel to Maastricht, including “The Last Scenery of Mind” (2023), a hodgepodge of images: faces, pieces of bread, animal shapes.

“In general, my works are inspired by plane surfaces, and I see them as the consciousness, which is like the starting point.” Ms. Chung, 55, said recently over coffee at the gallery. “What intrigues me the most is that people see a painting as two-dimensional, but my view is that it is not. Our eyes can only see three-dimensional objects. I believe that we can experience the multidimensional world through the color shape forms. They are the common denominators.”

There is a smaller and quieter piece, “Ice Breaking” (2022), which she described as simpler and more fluid than much of her work and as honoring the roots of her art education in South Korea.

“Maybe our professors’ generations were more inclined to look to foreign cultures because they are more advanced, but in our generation that idea starts to fade away,” Ms. Chung said. “Our professors’ generation affected us, but we are looking for our own artistic language.”

It’s that idea that is at the core of what the Page Gallery hopes to portray at TEFAF Maastricht as it blends the history and future of South Korean art.

“Many people think that Dansaekhwa is just overly hyped, but it’s the key to Korean contemporary art history because those artists are the touchstone to the next generation,” Mr. Ilwoo Huh said. “It’s important to highlight this flow from old to new art in Korea.”