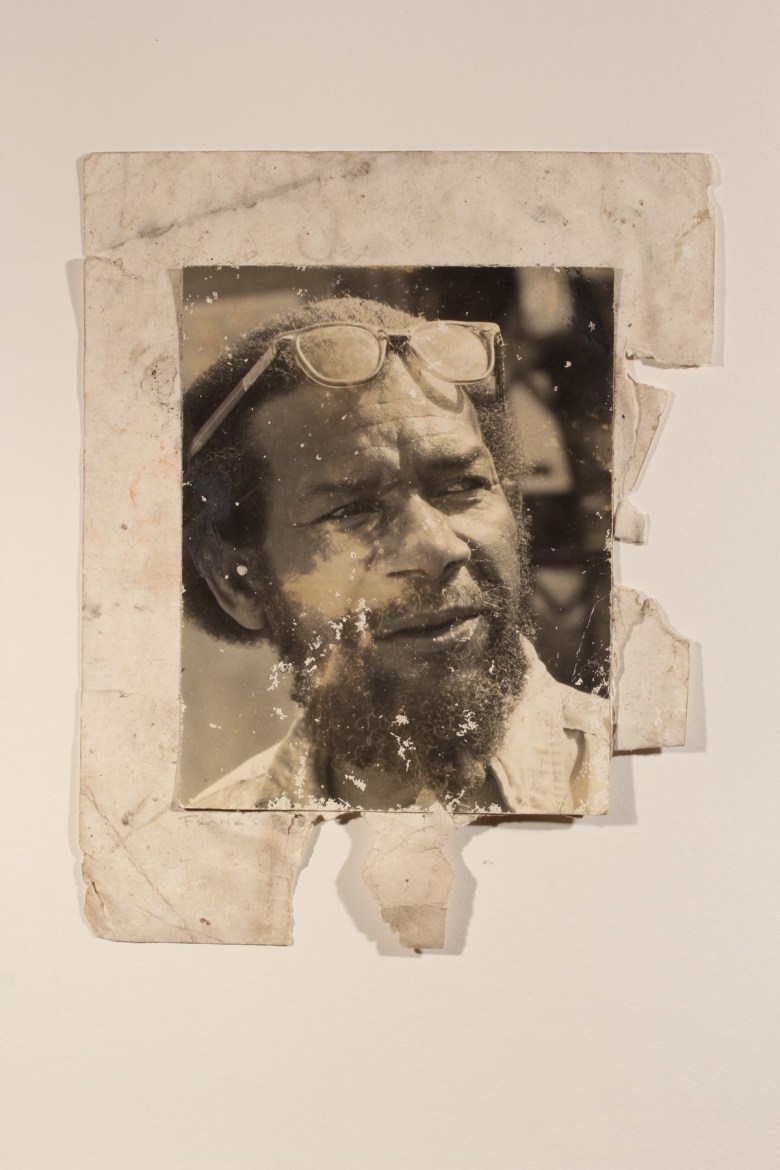

LONDON — The creative world of the late Frank Walter blends reality and imagination across a uniquely multifaceted oeuvre. He remains one of the most prolific artists, writers, and thinkers to come out of Caribbean culture, leaving behind a 50,000-page literary archive, as well as over 6,000 paintings and drawings, 600 sculptures, 2,000 photographs, and 468 hours of audio recordings. Stored for many years in his self-built home in a remote location outside of Falmouth, Antigua, several of his paintings have suffered damage from storms, tropical humidity, and multiple relocations, compounded by his frequent use of non-professional art materials.

Despite this unwieldy legacy, or perhaps because of it, Walter has been widely and lazily characterized as an outsider artist. Walter was an impoverished Black person making art in rural Barbuda and later Antigua, and struggled to find a wide audience and mainstream platform for his art beyond his own community during his lifetime. His subsequent designation as an outsider or amateur artist reveals the systemic biases within the international art canon along socioeconomic, racial, and geographic lines. This is due in part to the problematic primacy of White and European perspectives within art history. Scholar Barbara Paca, who curated Frank Walter: Artist, Gardener, Radical at London’s Garden Museum, told Hyperallergic that Walter was already “regarded as a phenomenon in Antigua” and recognized there during his life.

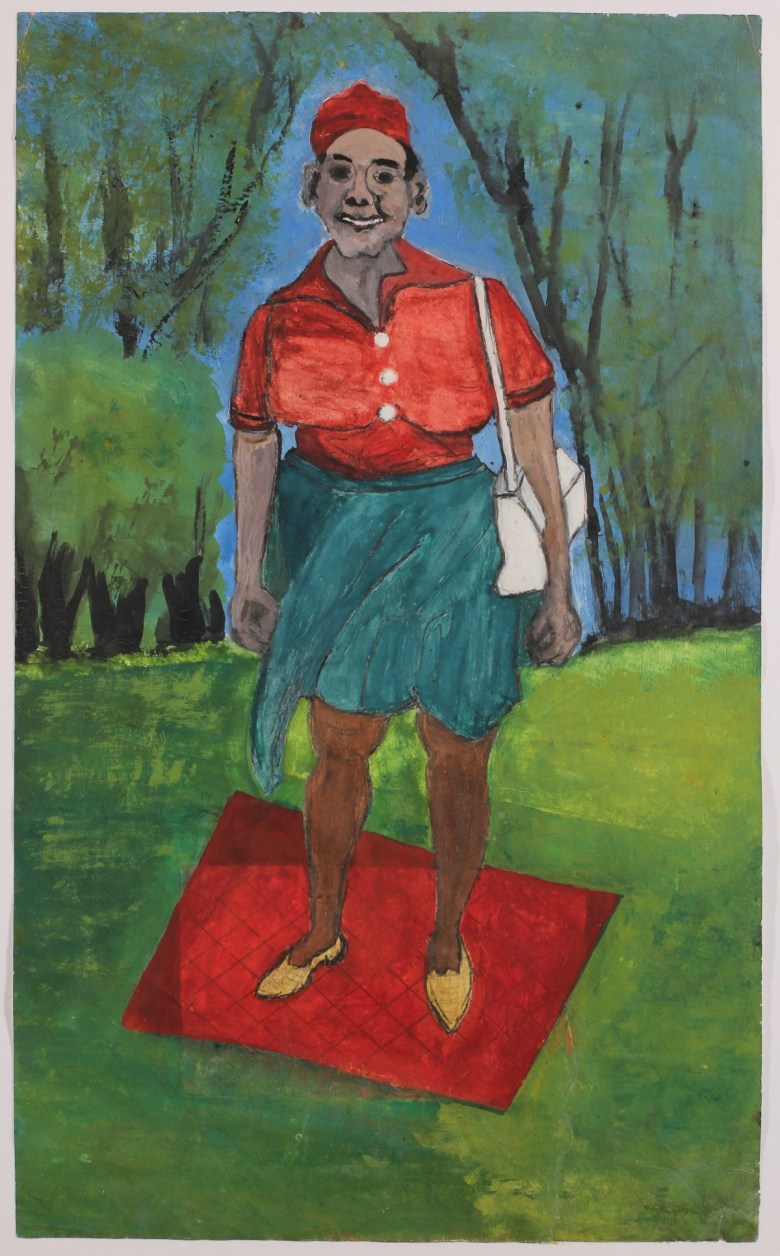

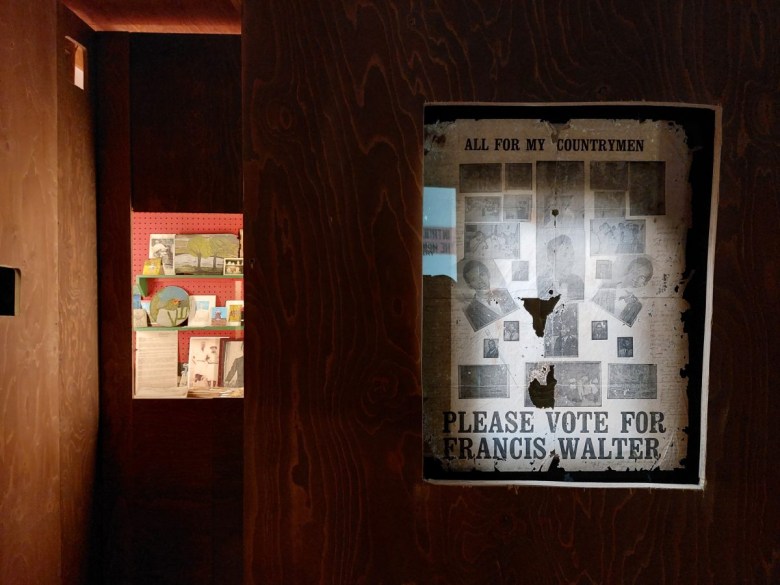

The exhibition, open through February 25, attempts to link Walter’s artwork to his wider ideas around politics and the environment. The artist’s paintings are displayed alongside objects from his studio, ephemera from his unsuccessful political campaign to become Antigua’s prime minister, and photographs of his open-air studio and garden. The artworks include self-portraits and a selection of small landscape paintings on the back of Polaroid film cartridge boxes. The exhibition attempts to contextualize Walter within his Caribbean landscape and cultural setting and challenge his characterization as an outsider artist.

Frank Walter, who was a direct descendant of both enslaved people and enslaving plantation owners, received a classical education at the Antiguan Grammar School, where he excelled in Greek, Latin, and math, before becoming the first person of color to manage an Antiguan sugar plantation at the age of 22. Determined to learn more about agricultural management and to access European culture, he traveled to England in 1953, where he faced systemic racism. Despite his qualifications and education, he could find only menial work and led a financially insecure, itinerant life until his return to Antigua and Barbuda several years later. These experiences led him to what Paca describes in the Garden Museum’s exhibition catalogue as a “preoccupation with his own origins under the steel-clad caste system of British colonialism.”

In his self-portraits, Walter repeatedly depicted himself as a White man, and often as a member of royalty. He also created huge and complex genealogical charts showing himself as the direct descendant of various White European royal families. Inspired by the fantastical oral histories passed down by his grandmother, he fully believed in these lofty origins, making them a keystone of his artistic imaginary.

In his texts, Walter writes about “Black Europoids” who he claims inhabited Antigua before the arrival of enslaved Africans. He argues in his unpublished 6,238-page autobiography that Antigua “began as an official royalist colony inhabited by exiled British peers,” conceptualizing it as the home of King Charles II’s illegitimate son and himself as a direct descendant of that child. This forms part of Walter’s complex idealization of some elements of whiteness and colonialism, even as he also sought a connection with Antigua’s Black and Native histories, as seen in his powerful paintings of Arawak ceremonies and traditions. He understood himself both as an exile and as deeply embedded within the colonialist system, right up to the inner circles of European society. His extensive writings also comprise poetry, including “From Leeds to Wetherby,” which encapsulates his sense of being both insider and outsider, both Black and White: “For tradition tells me that / I am but a seedling here in my strange land. / Transplanted!”

Henry Paget, professor of Sociology and Africana Studies at Brown University, told Hyperallergic that “Walter’s art was the largely spontaneous creative self-expression that accompanied the unfolding of his complex and multi-sided subjectivity.” He added that it was Walter’s “increasing turn to deep inner spirituality and lack of formal training that has led to him sometimes being labelled as an ‘outsider artist.’”

Barbara Paca and other art historians have recently worked to reclaim Walter as a key contributor to both Caribbean and international art. In 2017, Walter’s work was presented in the inaugural Antiguan and Barbuda National Pavilion at the Venice Biennale curated by Paca, followed by a major retrospective at Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt in 2020.

These efforts, in conjunction with the current exhibition at the Garden Museum, establish that to label Walter as an outsider artist is to compound the systemic othering he experienced throughout his life, particularly during his time in Europe. International affairs scholar Nina Khrushcheva said the radical completeness of Walter’s imaginative world-building occludes the “outsider” label. “Walter thought that his is the only art,” Khrushcheva told Hyperallergic. “There is no outsider about it: It is universal and complete, and everything and everyone else which does not exist in his imagined reality is outside and an outsider.”

Joycelyn Walter-Thomas, Frank Walter’s niece, similarly sees a timelessness in the artist’s commitment to his creative practice despite his experiences of systemic racism and being ignored by the art world.

“By freeing himself from the expectations of others, he inspired creativity and connection with creation and the Creator,” Walter-Thomas explained. “Frank’s quiet determination and ability to focus in a screaming world, his unapologetic, incredible truth in painting, drawing, writing, sculpting and taking photographs are timeless.” In other words, she said, “Art was his core and then there was everything else.”