There I was. In the booths of TEFAF—The European Fine Art Fair, for those uninitiated—the yearly event that lures the skinny-silk-suit-wearing, delicate cologne-scented collectors, the serious kind who neither want their names nor faces known by anyone other than the gallery founders who have previously sold them that Pieta or this Brueghel with no public fanfare, no auction and stashed away records that remain anonymous where provenance is concerned. As one Modern dealer quipped, “it’s really like a bank vault in here.” And not simply for the gatekeeping, there’s a sober tone. While of course there is no shortage of gilt—even the oyster shells are slathered in gold—in short supply are sidepieces and slick charades that have become synonymous with the art fair parade.

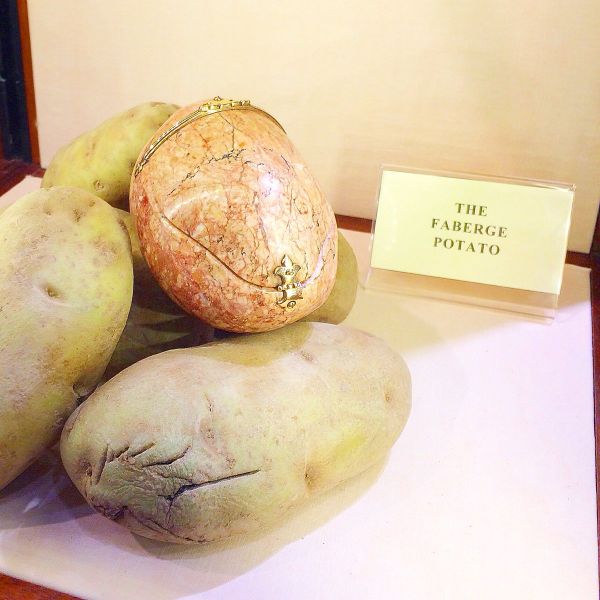

Inside this storied lair where thousands upon thousands years of history are for sale. The Faberge Potato (from a La Vieille Russie). Those weird ass “Moss” children by Finnish sculptor Kim Simonsson from Jason Jacques, the world’s fanciest pot dealer—no, really, he’s the man for contemporary ceramics. Six painted panels by Martin Battersby made for the drawing room of Chateau St-Firmin, whimsically installed in-situ at Lowell Libson. A smattering of original Gerrit Rietveld furniture, including a 1927 Beugel chairs and a Z chair from 1932, in celebration of De Stijl’s 100 anniversary at galerie Ulrich Fiedler; and no surprise here, an utterly zen booth from Axel Vervoordt showing that mixed his signature Roman bust collection alongside Kazuo Shiraga and Hyong Keun Yun.

TEFAF also always been a barometer of the art market, not simply because some uncountable number of objects spanning the centuries are on offer. But rather, it publishes its famed Art Market Report, which until this past summer was directed by Claire McAndrews, who poached by Art Basel released her first report for the Contemporary Fair behemoth just last week at Art Basel Hong Kong. This year, according to TEFAF, the overall market grew 1.2 percent to a $45 billion global industry. Paintings are still the art market’s bulwark currency, though being exchanged through dealer’s hands and not so much at the auction houses. In 2016, there was a 20 to 25 percent increase in dealer sales through privately brokered means; though there was about a 19 percent dip in dollar value of art, across the categorical board.

Amid the aisles of Wunderkammers, both in concept and quite literally—Burzio, an Italian antiques and fine arts specialist, filled its booth with Memento Mori and mechanical models that embody a cabinet of curiosities—it’s near impossible to shake the feeling that one is inside a market machine. That’s not a bad thing, of course. In fact, the endless rows are packed with the wonders beckoning to enter both the market, and perhaps more interestingly for culture vultures, the cultural production narrative. Here are sorts of things that should be catalogued and organized into the history of humanity, especially those that haven’t had the chance yet to for the many reasons that the cultural conversation is reassessing the perimeters and representations these days.

Strolling past a very clean, well-lit and somewhat staid booth, A Young Man Smoking a Pipe caught my eye. Any fan of Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi would notice the transcendent face, the tactile fur of his hat and compositional chiaroscuro. The boy’s stare is one of concern, either on behalf of the viewer or whatever has affixed his gaze. It’s a great painting, regardless if you know just who’s behind it. Turns out: Michaelina Wautier. Who? Exactly. A lady painter. She lived almost the entire course of the 17th century, but naturally for centuries her work was either misattributed as her brother, Charles, or even more famously to Artemisia (even though they never quite crossed paths). She isn’t exactly a household name—or really one of the handful of female artists who made it out of the Baroque with a reputation and an intact oeuvre. If you’re scratching your head, think Judith Leyster, Josefa de Obidos and Elisabetta Sirani (who back in 1665 joined that mysterious 27 club, hrmm). But she’s a powerhouse with a paint brush, but as we know, she had to be.

There are either 26, 29 or 30 known canvases of Michaelina, which according to Sander Bijl, who is selling (or sold, and quite hush about either way) the “Smoking Youth,” from 1617 to 1618 by the way, only in the last couple of decades did auction specialists start to realize that Michaelina’s hand was quite distinct. I stumbled over when van Bijl Van Urk (Bijl’s gallery) said auction specialists. Market men, always on the hunt for an undiscovered artist…and these days, the art world has some boxes to check. Yet, it was indeed the auction specialists and Katlijne Van der Stighelen, a Van Dyck scholar at the university in Leuven (Belgium) who uncovered the mistake surrounding a self-portrait that for ages was misattributed to Artemisia. In fact, der Stighelen has plans to unveil an exhibition surrounding Michaelina in 2018 at the Rubenshuis (Peter Paul Rubens Museum) in Antwerp. As I talked to Bijl, who said “she paints like a guy,” then corrected himself, “she really is one of the best painters,” he recommended I go see Michael Weiss Gallery, where grumpy portrait of Martino Martini (a name to remember) by Michaelina got the front-n-center treatment in the London dealer’s booth. The same canvas hit the block a year ago at Köller Fine Art and sold CHF400,000 ($395,000) with an estimate of CHF7,000-CHF10,000 ($7-10k).

So, those motivations of bringing Michaelina to light: To be fair, she’s in private collections and national museums in the Flemish region (both in NL and BE) so it’s not like the name Michaelina Wautiers (Wotiers) has never been heard through the course of history. However, the precise details of her life, they remain at large in the lost files of life. That being said, overlooked female painters are a necessary inclusion to the narrative of Western painting, the kind that’s still foundational to arts education and the discipline’s historicization. I, a woman, should be bursting with joy that a bunch of old white men, with the help of a lady academic, are righting the course of history that relegated women “too impressionable to paint the male nude figure,” as my college art history professor put it. But, with some 30 known and attributed canvases, I’m going to need something stronger than Botox to keep these eyebrows from raising. That right there is a dealer’s wet dream. A highly controlled market for an untapped well, called a discovery—a woman artist from the 17th century. Cha-ching-cha-ching.

Writing of the inclusion of women into the art historical narrative, while of course it only checks one box off for demographics—and sure, we are still only talking about European painting in art history which is a European-designed discipline—is an imminent task, one that will be inherently imbued with market forces. Again, that’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it certainly adds to the same-old, same-old rigmarole of who gets written into the history books and who continues to profit financially, thus who controls institutional play (since that direct line is a rather transparent one, these days). Will Michaelina really ever have a market like Vermeer, whose biographical conditions are quite similar to hers? I’m betting not, unless her 2018 Rubenshuis show becomes a blockbuster and tours the world, and the private collectors who hold her works decide to sell or the slew of landlocked European nations’ museums see a deaccession as a strategic move for cash flow.

We are in a crucial moment where inclusion should be the agenda. Erasing the past is a feckless enterprise—look at those who do: they’re philistines who destroy monuments they deem idol-worship. Voices from all aisles, and in this globalized conversation, especially at the artistic and curatorial level, there are beautifully complex perspectives to be listened to and heard, and given authority to write the arcs of history that best suit each narrative and role in the larger organism. This not only apply to minority voices, particularly People of Color, LGBT+, Jews, Muslims, Disabilities, non-binary everything—but a parallel task falls upon white people, in all their diversity (JK) from the basic bitches to the red necks and everyone in between. There needs to be a candid, frank white narrative about the atrocities committed by White peoples, from the Vikings through the US Corporate Overloads and let’s not forget…men…who have inflicted suffering upon so many communities globally, whether on home soil or in unfairly colonized lands. How that affects art: that means what gets shown in institutions, whose catalogue raisonnés are written, who receives artist grants, and who the market is favoring at the moment is the highest caliber of cultural producer from their unique background—and there’s an even spread of these cultural producers. It also means opening up the annals of history.

Is this simplistic? A bit. But is it possible in a contemporary context. History sits before us, and we needn’t fall yet into an Angelus Novus. For long gone history, that of course is a bit trickier—and comes with a price, an easily co-opted one where the potential to capitalize on correcting mistakes making the whole enterprise feels circular. But even if someone like Michaelina is, as Stighelen puts it, “even more astonishing than Artemisia Gentileschi,” and “reminds us of the most outstanding Baroque painters such as Johannes Vermeer and Michaël Sweerts.” Why give primacy to the dudes and pit the women against each other?

So here let’s start. Michaelina and Artemisia were bombass painters who despite European trends in portraiture and subject painting at the time managed to transcend the humanity of subject, and technical properties and formal constraints of Baroque painting by imbuing their canvases with diffuse light and compositional luminosity that even now commands attention in most sensitive ways. Michaelina may have painted the safest subjects available to her, (though maybe not, as there are so many unknowns); however, the best of art, across the board, leaves the suspicion that there’s something more, and artistic intent shouldn’t sway any such subjectivity. So while it’s no doubt exciting that Michaelina is finally getting the attention she deserves, can we begin by not contextualizing her output not in competitive terms? Guarantee, she’ll still sell.