Fans, gowns, beaded dress pumps, even a French hat ornament constructed from the stuffed body of a bird-of-paradise, complement the 50 paintings assembled for “Fashioned by Sargent” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, currently on view through January 15, 2024. The exhibition focuses on American expatriate artist John Singer Sargent’s relationship to fashion, demonstrating how he used costumes and textiles to frame his subjects and show off his artistic virtuosity.

The costumes are splendid; some of them, such as the black taffeta and pink-silk-lined opera cloak that belonged to Aline Caroline de Rothschild, Lady Sassoon, are restored heirlooms kept in the families of the sitters for generations. Others are approximations of the clothes Sargent’s subjects wore, such as the piece of antique lace and swatch of tapestry that nearly match the Velázquez-like costume that Jewish British collector Mathilde Hirsch posed in.

As you go through the galleries, you can see how the artist draped shawls, pinned back silks, and carefully arranged bulky hoop skirts to create windows for light and color or opportunities to exercise the wild joy of his rapid brushstrokes. But what actually stands out is the extraordinary lucidity of Sargent’s characters. You can’t help feeling you’ve seen the faces before.

Even though it might be the figure of a countess who lived well over a hundred years ago, there is a resemblance, you think, to someone you know. Many of these are Jewish faces, and this isn’t surprising, since Sargent had a number of Jewish friends and Jews stood out among his most important supporters.

Sargent, who was born in Florence in 1856 and died in London in 1925, didn’t leave behind a diary or journal. Most of what we know about his personal life, or his relationship to his upper-class Jewish patrons living in late-Victorian or Edwardian England, comes from people who knew him or from his own slapdash correspondence, scribbled in an eccentric handwriting. At the turn of the century, he was the most sought-after portraitist in Europe and America, charging 1,000 guineas for a painting, equivalent to about $161,000 today.

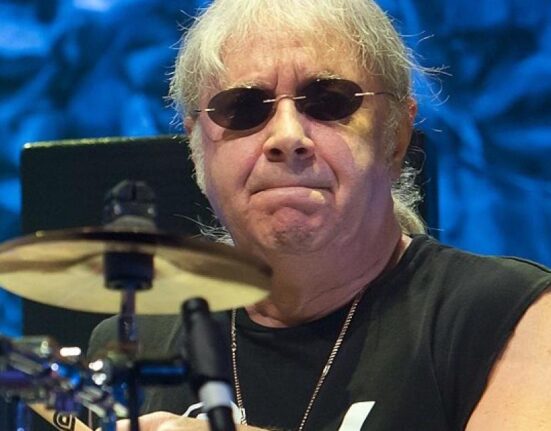

Portrait of Ena Wertheimer: A Vele Gonfie, 1904. Sargent outfitted Ena with a man’s ceremonial court coat and a cavalier’s plumed hat to show off her vitality. Photo credit: Tate: Bequeathed by Robert Mathias 1996)

Biographers who knew him charac- terized Sargent as an autodidact who was meticulously orderly with his work schedule but otherwise otherworldly, disengaged from current events and uncomfortably shy in the highest society, where he was known to “splutter” and grasp for words. He had grown up in an eccentric family that left Philadelphia for Europe when they were in mourning after the death of their first-born child. While his father was trained as a surgeon and his mother had a small amount of inherited wealth, they were not rich and lived an itinerant life in rented rooms, moving from city to city.

Sybil Sassoon (The Countess of Rocksavage), 1913. For his wedding portrait of Lady Sassoon’s daughter, Sybil, Sargent had her wear one of his favorite props, a Kashmiri shawl. (Photo credit: Private Collection)

Sargent was not formally schooled until his talent as an artist was recognized. The roots of his education were in museum galleries, where his mother taught him to copy what he saw onto a drawing pad. When he was 18, he enrolled in the Paris atelier of the portrait artist Carolus-Duran, who revered the work of Frans Hals and Diego Velázquez. In the studio, Sargent was a star. Among friends—those who shared his love of literature, theater, art and music (he was a gifted amateur

pianist)—he was genial and warm. His circle included members of several distinguished Jewish families who are represented in the show: the Sassoons, the Meyers, Mathilde and Leopold Hirsch, and Asher and Flora Wertheimer.

This was the time when the wealth of England’s aristocracy was diminishing, and America’s robber barons and Jewish financiers were perceived as a threat to the old social order. Art historians have suggested that as an American living in England and, most probably, as a closeted gay man, Sargent felt an affinity with London’s assimilated and cosmopolitan Jews, who were insiders and outsiders just as he was. Together they navigated racism and bigotry, since they were living in the era when Oscar Wilde was sentenced to prison for indecency and Parliament passed the Aliens Act, designed to restrict immigration of the “wretched” Jews fleeing Russia and Eastern Europe.

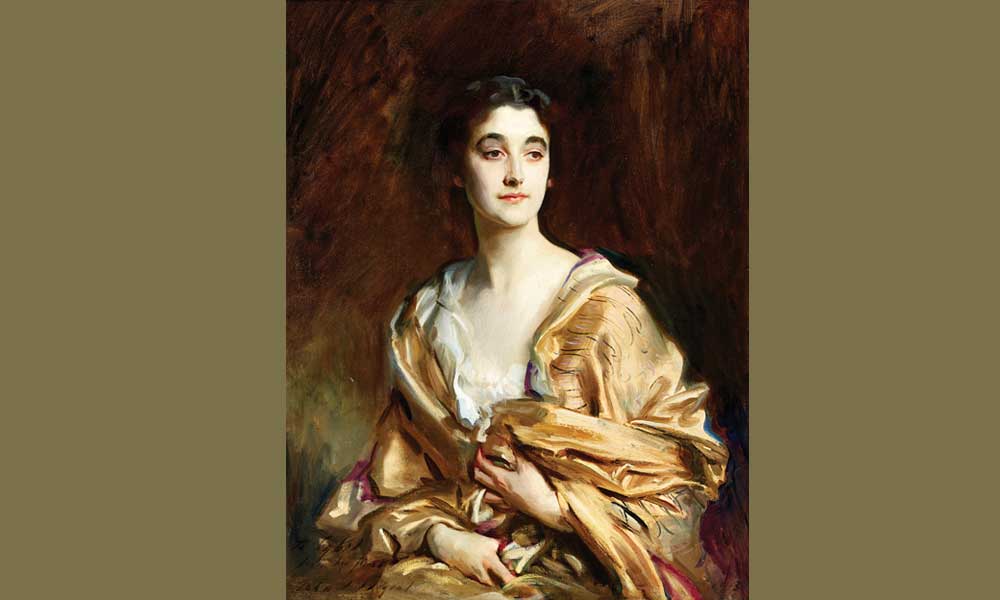

Mrs. Carl Meyer and her Children, 1896. Mrs. Meyer’s billowing gown, an artistic invention that blended the sitter’s real gown with a mix of dresses drawn from Sargent’s memory and imagination, takes up almost half the picture space of this arresting family portrait. (Photo credit: Tate: Bequeathed by Adele, Lady Meyer)

One of the tour-de-force paintings in the exhibition, Mrs. Carl Meyer and her Children, from 1896, gives viewers a lot to think about, both in terms of Sargent’s gift of imagination and the complexity of his relationship to his Jewish patrons. At the time of the painting, Adèle Meyer was known as a gracious hostess and philanthropist. Her father had made a fortune as a rubber manufacturer, but she augmented her social status when she married Carl Ferdinand Meyer, who was the foreign emissary for the British Rothschild bank before becoming London’s chairman of De Beers. Although the Meyers had been raised as Jews and were married in a Jewish ceremony, they chose to have their three children baptized and were themselves buried in a Christian cemetery. The rococo extravagance of Sargent’s composition, with its textures, colors and richness of materials, acknowledges the family’s immense wealth as well as Adèle’s abundant energy as a suffragette and benefactor of many charities helping children and women.

The choreography of gestures at the crux of the painting is as complex as any scene from a Henry James novel: A beautiful, self-assured woman holds an open fan in one hand while her other hand reaches up to her children. Her beribboned arm connects her world to theirs as she lightly touches her son’s fingers, and her daughter protectively wraps an arm around the boy’s shoulder. Sargent has caught the familial attachment with dexterity, all distilled in a single narrative moment. The immense, peach-colored gown was apparently an artistic invention, pieced together from the real gown Mrs. Meyer wore and a concoction of dresses Sargent drew from his memory and imagination. It was daring for Sargent to allow the billowing skirt to take up almost half the picture space, while his unusual foreshortened perspective creates a sense of stable instability. Art historians have wondered whether that was intended as a reference to the precariousness of the nouveau riche Jewish family’s social position. Though most critics acknowledged the achievement of Sargent’s painting, that didn’t stop truculent remarks such as the one from The Spectator that read: [Sargent had] “not succeeded in making attractive these over-civilised European Orientals.”

Two years after Sargent painted the portrait of the Meyer family, he began work on his largest commission, from the Jewish art dealer Asher Wertheimer, who had Sargent paint 12 portraits of his wife, ten children and many dogs. Before the commission, Sargent and Wertheimer had traveled in the same circles because of Wertheimer’s business, which specialized in 18th-century French furniture and Old Master paintings. But the friendship with the family grew over the many years Sargent worked on their portraits; he was quoted at one point as saying, “I’m in a state of chronic Wertheimerism.”

It was said that Sargent especially admired the liveliness of the Wertheimer daughters. The poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt wrote in his diary, “[Sargent] paints nothing but Jews and Jewesses now and says he prefers them, as they have more life and movement than our English women.” This, of course, is not accurate, since Jews made up a small percentage of Sargent’s clients; out of the 1,400 or so portraits he did during his lifetime, perhaps only 40 of them are of Jews. But Sargent did become especially good friends with Ena Wertheimer, Asher’s oldest daughter, and two paintings of her are included in the Boston show. One has come to be known as A Vele Gonfie (Italian for In Full Sail). The painting was a wedding present from her father, celebrating her marriage to the financier Robert Moritz Mathias. Many years later, Ena secretly sold the portrait in order to raise funds for an art gallery that she owned, substituting a copy that had been made by one of Sargent’s assistants. When her husband found out, he was furious; it took him years to track down the American collector who had purchased it and to buy it back.

The exhibition catalog includes a photograph taken at Ena’s wedding. It shows her serenely seated, dressed in a majestic beaded wedding gown with an extravagant train. In contrast, Sargent’s three-quarter figure portrait of Ena, far from bridal, captures her dash and ebullience. Apparently, she had rushed into his studio one day, characteristically late and impatient about the tediousness of posing for her portrait. Sargent noticed that her coat seemed to be billowing with the wind and this gave him the idea to paint her in a way that would show off her animation and vitality. The portrait that transpired grew out of a collaboration, a theatrical play in which Sargent suggested she put on a man’s ceremonial court coat and a cavalier’s plumed hat, transforming her from a young Jewish woman into a dashing aristocratic man with the swagger of one of Sargent’s beloved Frans Hals characters. The masquerade freed Ena from the constraints of traditional portraiture and gave her the ability to move into her own identity. Looking over her shoulder while stretching her gloved hand across her chest, she grasps onto what appears to be a cloak that’s about to blow away; she’s “in full sail.”

While the monumental portrait of Lady Sassoon subsumed in her black taffeta opera coat is hung at the start of the exhibition, the more intimate wedding half-portrait of her daughter Sybil Sassoon, the Countess of Rocksavage, comes at the end. Together, they form bookends to an exhibition that is as much about friendship and patronage as about the expressive power of costume. Part of Sargent’s genius lay in his ability to join forces imaginatively with his subjects. Fashion and props could help him crystallize characters or draw out fantasy. One of his favorite props was a Kashmiri shawl, which he used in Sybil Sasson’s wedding portrait. In England at the turn of the century, such a shawl would have been imbued with an array of ideas about the faraway Orient, a place of imagined beauty, artistry and pleasure. What should we make of this portrait Sargent painted of someone who might accurately be called a Mizrahi princess at a time when the idea of an “Oriental Jew” was an antisemitic trope? Or that Sargent gave Sybil the Kashmiri shawl as a wedding gift?

The painting is a demonstration of some of Sargent’s freest brushwork. The young woman’s face seems almost to be built sculpturally, as if the bone structure were modeled by clay rather than paint. The shawl, with its many draped folds, is a riot of paint strokes. And when you look at Sybil Sassoon’s gaze, you see nothing but trust in her intelligently serious eyes.

Opening picture: Lady Sassoon (Aline de Rothschild), 1907. For her portrait, Lady Sassoon donned a black taffeta and pink-silk-lined opera coat that had been in her family for years. (Photo credit: Private Collection Image © Houghton Hall / all images Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)