FANBOYS, REDDIT TROLLS, Greta Gerwig—they all seem to have an opinion of Zack Snyder and his work, which most people have decided are the same thing. “Love him or hate him,” Snyder says of his outsized reputation. “A lot of intellectuals— I don’t know what you would call it, the cinephile-elite-genre-press people—are kind of anti-me for whatever reason.” He proceeds to quote an article that said: “Zack Snyder probably masturbates every time he says cut.”

Here the person responsible for more than $4 billion in box-office receipts screws his face up. “I was just like, Really? You think that’s a cool thing to say? Because you have this perception of me as some sort of supermacho—I don’t think I’m a macho dude. I’m interested in masculine tropes. But as tropes.”

Man, those tropes will trip you up. Perhaps it was the hypermasculine tone of his breakout film, 300, a sword-and-sandal epic from 2007 that introduced audiences to both Snyder’s graphic, slo-mo violence and Gerard Butler’s cobblestone abs. But the worst you can say about that movie (which spawned a popular Spartan workout) is that it was a perfectly mindless thrill—like Gladiator for people who can’t read good. Which is precisely the kind of snarky commentary Snyder would hate.

Nothing crystallized his divisive public image more than the relentless social-Åmedia campaign run by fans demanding: “#ReleaseTheSnyderCut.” For about a decade, Snyder had been the architect of the DC cinematic universe. He directed two stand-alone Superman films, hand-picked Gal Gadot to play Wonder Woman, and was generally charged with maintaining a singular vision for this beloved IP. But his 2017 cut of Justice League left Warner Bros. executives wanting, and after weathering a devastating personal tragedy, Snyder left the project entirely.

Justice League went through extensive reshoots by another filmmaker. And when that Frankensteined film disappointed critics and accountants, Snyder’s Justice League took on mythic proportions. Fanboys rented a billboard in Times Square at an estimated cost of $50,000 a day that said #ReleaseTheSnyderCut. More troubling were the tweets; as the Snyder Cut became the white whale for an army of trolls, the worst among them started threatening the lives of studio executives at Warner Bros. The security division had to get involved.

The conversation around Snyder hit a fever pitch this past summer with a punchline in (of all places) Barbie. The moment arrives relatively late in the story, though it hits precisely at the film’s emotional climax. Ryan Gosling’s Ken has brought the patriarchy to Barbieland, brainwashing women into submission. But as the Barbies wake up—thanks to a powerful feminist battle cry delivered by America Ferrera—one of the dolls mutters: “It’s like I’ve been in a dream where I was really invested in the Zack Snyder Cut of Justice League.”

Say what you will about the joke (and people have said a lot), but can you imagine making billions of dollars in profit for a studio only to have it turn around and make you the butt of a joke in its biggest summer blockbuster of all time?

Holy whiplash, Batman!

“THEY GAVE US a heads-up,” Snyder reveals here for the first time. Warner Bros.’ new CEO, Michael DeLuca, was talking to Snyder’s wife and producing partner, Deborah Snyder, earlier this year. “And he said, ‘Hey, there’s a reference to Justice League in the movie. It’s cool and whatever, I hope you guys understand, we think it’s awesome.’ ”

This was hardly the first joke at Snyder’s expense. (He’d already been pilloried on The Simpsons—“Un-release the Snyder Cut”—and on Amazon’s The Boys.) But it was certainly the most visible. The Barbie movie has already made more than $1 billion in global box office. To his credit, Snyder didn’t run from the moment. He had a barbecue, inviting a bunch of friends over to watch Barbie in his private screening room, where plush alpaca blankets from Restoration Hardware warm every one of the 16 recliners, and they all shared a good laugh at their host’s expense.

“I thought [Barbie] was great,” Snyder says with boyish enthusiasm, “and I think the joke is pretty good,” saying it’s more a crack about the fandom than it is about him. “A hundred percent,” he says. But on the eve of arguably his most ambitious project yet, a two-part space opera for Netflix called Rebel Moon, he admits the joke also left him slack-jawed.

“The thing that I said to Debbie is—the thing that you need to take a second and think about is that your name is so seamlessly sewed together with a pop-culture phenomenon so big it can exist as a joke in a movie about Barbie. That’s pretty insane. You just need to step back for a second and go like, ‘Whoa, what did we do? What happened? How is that a thing?’ ”

That Snyder would become the town’s poster child for red-pill bros wasn’t his plan. And he’s quick to say he can’t control his fans and wouldn’t dare try. “I don’t feel like I’m the moral police of the Internet. It’s a pretty righteous move to assume that my morality is somehow above the morality of these people that I don’t know.” (His wife argues the toxic fans are a tiny subset of what is an otherwise supportive community.) Does Snyder feel misunderstood? “Sometimes I do,” he says. Or, put another way, he offers: “So you’re like, ‘Oh, Snyder’s a fucking male, toxic masculine fuck.’ I have fucking nail polish on my fucking thumbs, for God’s sake.”

Snyder was born in Wisconsin, and the family later moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts. His father was an academic, but his mother was perhaps the real influence. An eccentric artist, she made ice sculptures on the front lawn and pulled her son out of school to see Star Wars. On New Year’s Eve, she once decided to celebrate by painting a mural on a wall of the family home. “She was always creating,” Debbie says.

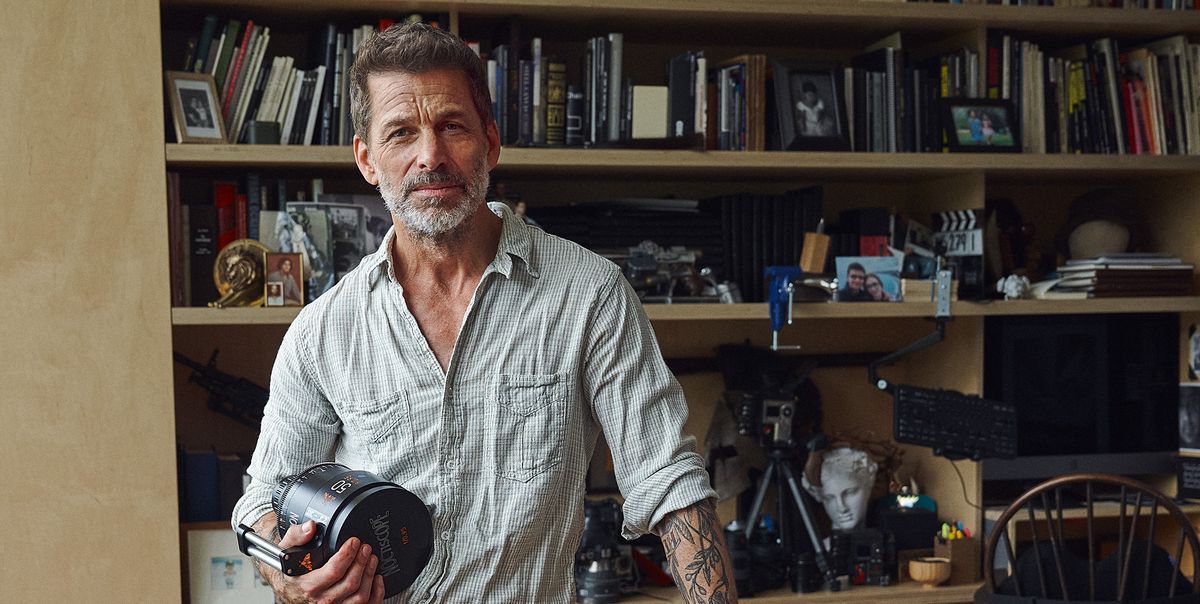

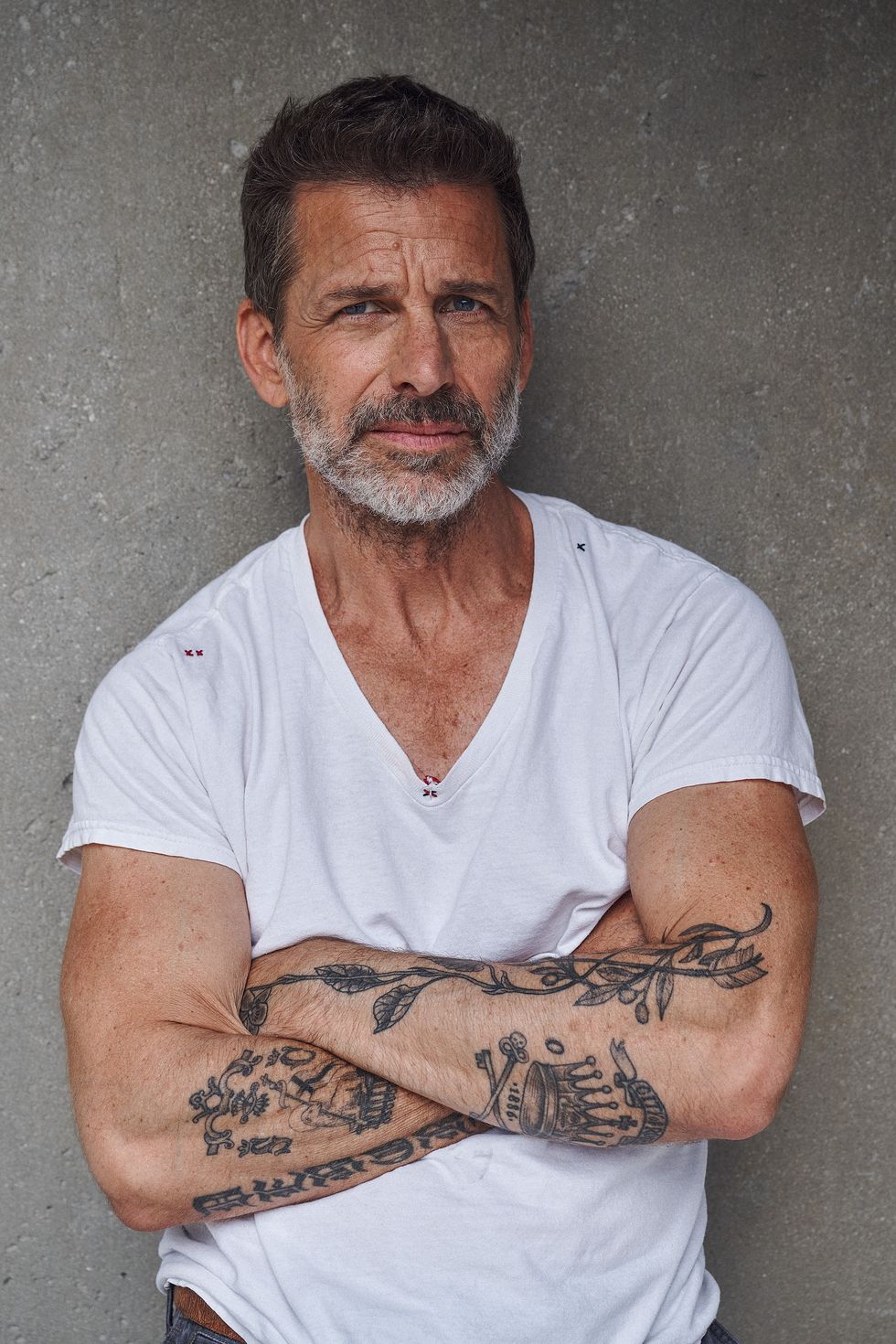

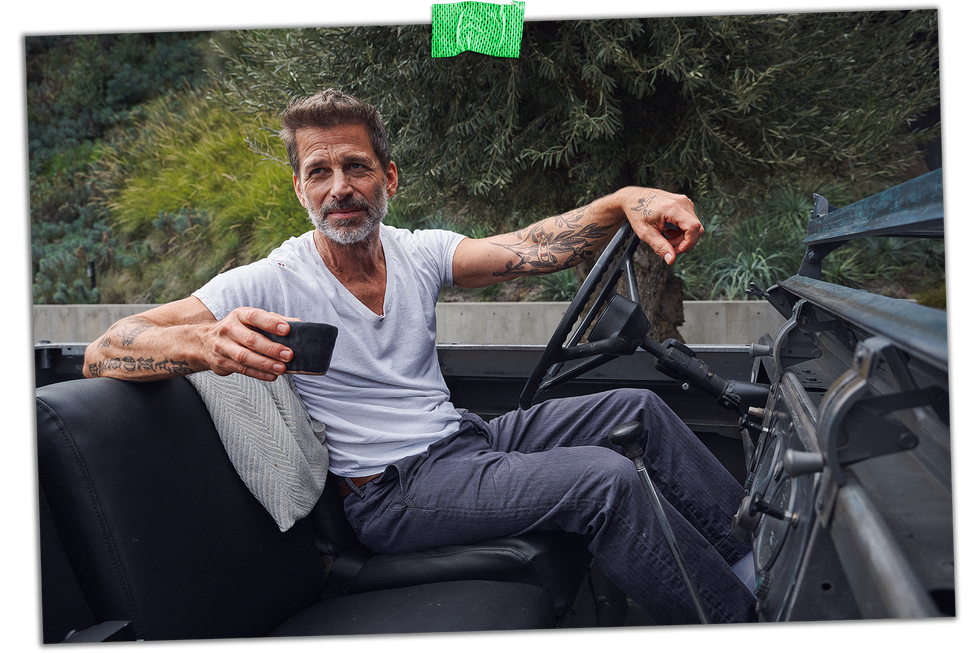

He studied fine-art painting in London before enrolling at Pasadena’s ArtCenter College of Design. He has an artist’s eye for detail—an aesthetic-takes-all philosophy of design down to his own body. (The 57-year-old’s perfectly worn-in T-shirt betrays a ripped, sinewy physique.) We’re seated in his office—a glass box jutting out from a Pasadena hillside, which he knowingly likens to the “lair of a supervillain.” But the joint is warmer than that—lived-in, filled with mementos and inspiration from his formative years. First-edition comic books (including Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles) line the bookshelves; a Helmut Newton print hangs on the wall.

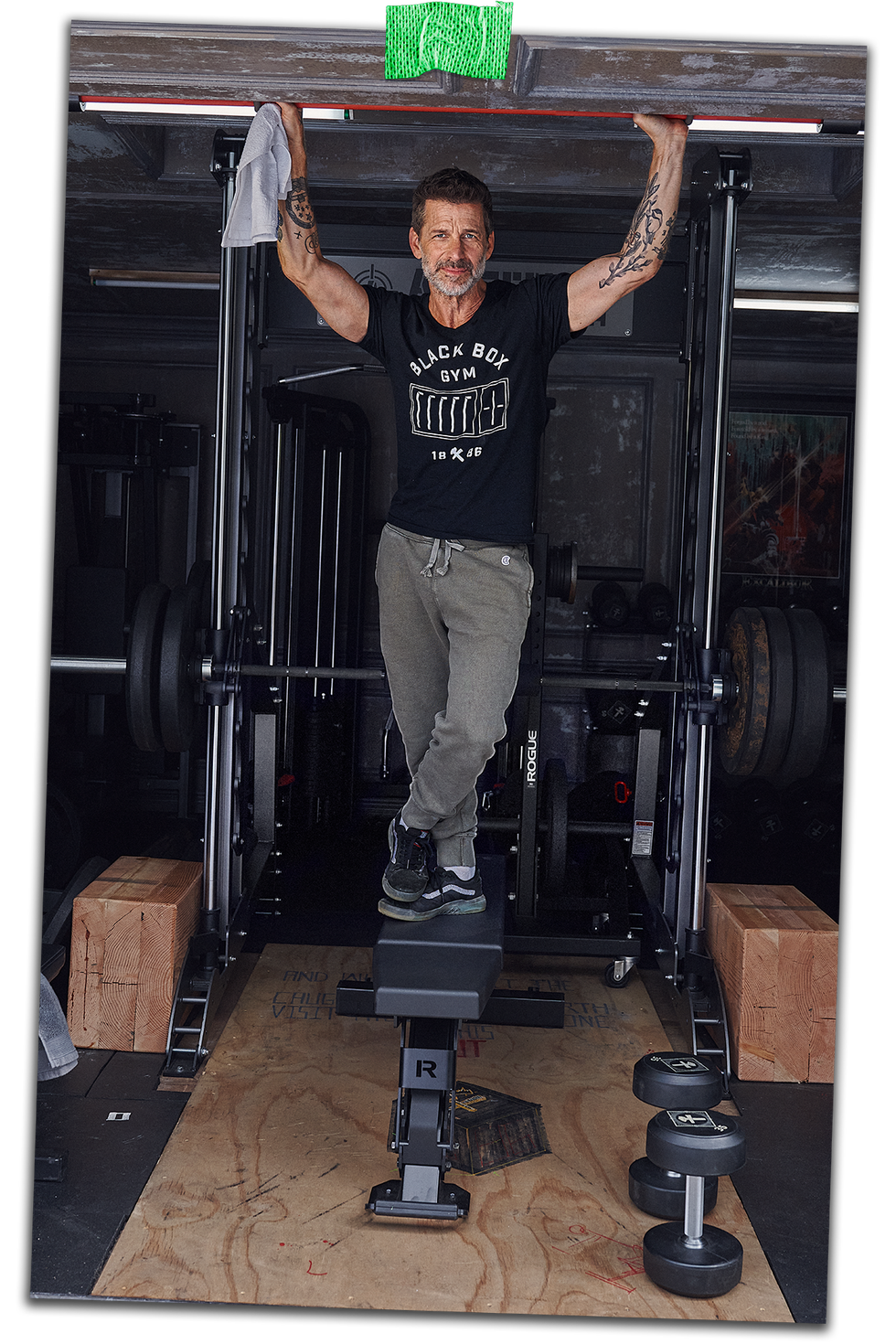

Snyder has seven kids (from different marriages and relationships), and his family lives just up the street from the office. His personal gym, mostly outfitted by Arsenal Strength, is on the property. (“I just always find the gym is a great place to kind of let everything go,” he says.) He’s also installed a pottery studio here inside a shipping container, where he’s been working on crafting the perfect coffee mug. Elsewhere, a 1966 Land Rover is parked in the driveway—minus the hard-shell top he recently had torn off. Of the truck, he says, “It’s like everything. It’s just a project. I like projects, obviously.”

Nothing in Snyder’s life is ever really finished, least of all his films. “My editor, she always says the movie’s never finished. They just end. Because they have to be released.” He’s not exaggerating. Snyder’s done extended versions—the mythic director’s cuts—of nearly every one of his films, dating back to the first, 2004’s Dawn of the Dead. His latest, Rebel Moon—Part One: A Child of Fire, a Kurosawa-meets-Jedi PG-13 flick on Netflix in December, is the rare unreleased film that will be followed with an alternate R-rated director’s cut.

Rebel Moon concerns Kora (Sofia Bou-tella), a former member of the dark Imperium who seeks redemption by recruiting a ragtag group of warriors to take on the fascist regime. If it sounds like the setup to a Star Wars movie, well, the project began as a Lucasfilm pitch. The Jedi overlords passed on it, which didn’t shock Snyder: “They had their own ideas about what they wanted their Star Wars universe to be. That’s fair.” He later took Rebel Moon out as a potential TV series (“I’ve had bad luck in pitching TV shows for whatever reason”) and then a video game before Netflix bit.

Snyder calls the idea “relentless,” likening moviemaking to excavating a mineshaft. “You crack open the earth and you start digging,” he says. “And I think that this movie, I was mining the stuff that I really love. It’s a love letter to the movies that made me love movies.” Star Wars, Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (whose sweeping Texas landscapes are reimagined here), Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai—it’s all on display, along with a healthy dose of fantasy courtesy of Heavy Metal, a vintage magazine his mother mistakenly gifted to him when he was 12, not realizing “it was very European—it’s like sex and violence.”

That’s certainly enough to launch a space epic. (A sequel, Rebel Moon—Part Two: The Scargiver, is due out next year.) But these are more than childhood obsessions. In a way, they’re breadcrumbs to Snyder’s psyche. Or perhaps they’re scars. When Snyder was 13, he tells me, his older brother Sam was killed in a car accident. Here he stands up and moves to the bookcase to retrieve a small framed photograph of his brother, like a school portrait in a series cut impossibly short. His brother is 19 and he has long hair. He looks like Jesus.

Sam’s death, he says, “sent me deeper into my love for movies—as an escape, as a way to deal with it. I needed some metaphors to help me. In the mythology of our family, he was the spiritual leader. When you’re 19 and you pass from the world, you leave a mark on it. You are immortal in that state—that youthful, magical person is locked in.” A picture comes into focus of a kid whose hero was taken away from him. Around that time, Zack read Arnold Schwarzenegger’s first book on bodybuilding and started to work out himself—maybe as a way to exert some control on an out-of-control world. His lionizing of the male physique—on display in all of his films, including Rebel Moon—comes into focus. His Superman was never going to be a slight Christopher Reeve. It had to be a yoked He-Man.

SNYDER HAS EXPERIENCED more than his fair share of loss, as if loss is ever fair. I’d argue Barbie’s Snyder Cut joke works better if you’re not familiar with what was happening in Snyder’s personal life around the time the Justice League mess began. While he was deep at work on Justice League, Snyder’s 20-year-old daughter, Autumn, took her own life. Autumn (from his first marriage, to Denise Snyder) was a student at Sarah Lawrence College at the time, and she’d recently written a sci-fi fantasy novel about an outsider struggling to fit in.

Snyder had never intended to make her death public. He and Debbie tried to power through the production, but he quickly realized the thing to do was to go home. “I was at a place after Autumn and after Justice League where I just kind of felt like there needed to be a reassessment of the why of everything,” he tells me. Justice League would be reshot by The Avengers’ Joss Whedon, who amped up the comedy and cut back on Ray Fisher’s turn as Cyborg—a move Fisher alleged was racially motivated.

The dark tone on display in Snyder’s DC films was MIA. And the fans went full tilt demanding the studio “#ReleaseTheSnyderCut.” Snyder declined to intervene, insisting today that it wasn’t his place to ask his fans to stand down. “I felt like my relationship with the fans is really one-way,” he says. “I give, I deliver, and I share with them ideas that I have. I am 100 percent against anyone threatening and doing anything to bully. That’s not cool, but that’s also obvious.”

Again, what else could he say? It’s hard to kneecap your fans when they’re responsible for giving you maybe the most unlikely second chance in Hollywood history. They’re responsible for the world seeing the film that Snyder always wanted to make. In the run-up to the launch of HBO Max, the studio finally engaged with the fans, imagining the Snyder Cut as the kind of must-subscribe event that would get people to pay ten dollars a month (or whatever) for yet another streaming service. The studio eventually gave Snyder about $70 million to finish the movie his way, which required shooting additional scenes during a pandemic lockdown, reportedly violating safety protocols (which Snyder denied).

When the long-awaited Snyder Cut came to HBO Max in 2021, it was more than four hours long. Among the scenes the director added was an epilogue between Ben Affleck’s Batman and Jared Leto’s Joker in which Batman threatens to kill his archnemesis, prompting the Joker to crack: “Who’s gonna give you a reach-around?” It was an ad-lib on Leto’s part (and true to that actor’s camp take on the role). But Snyder went with it: If this was his last chance to direct a DC film, as a fan he needed Batman and the Joker to meet. The Snyder Cut also restored Cyborg’s journey (reminding audiences how good Ray Fisher could be). And perhaps most important, a billboard for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention was inserted into the film with the message “You are not alone.”

Says Snyder: “Regardless of how you feel about the movie, whether it’s good or bad or whatever, just existing as it does at that level—at that price point with those characters—it literally should not exist. And I am incredibly grateful for the fans and for the circumstances that led to it, because it really is a personal, cathartic piece, working out a lot of demons in a giant 1.43:1,” referring to the IMAX-friendly proportions.

“I hate the circumstances,” Snyder adds. “But this is true of all things in your life. A lot of times you find a turning point that is not the way you’d want it.” He goes on to tell me about a book he read called The Dancing Wu Li Masters, about quantum physics and a “dramatic turn you didn’t expect helps you see past the physical to something more.” He adds: “Hopefully from the pain generates some kind of growth. It’s like a forest fire that hatches seedlings.”

THERE IS A lot at stake for Snyder these days. He is extremely famous—the kind of Hollywood personality who is suddenly recognized on a family trip to a theme park. But he’s also in some ways starting fresh. After a decade trying to please fanboys (and the multinational conglomerates that own their favorite iconic characters), Snyder is finally playing in his own sandbox—creating characters and worlds out of whole cloth (or greenscreen, at least). Was that part of Rebel Moon’s appeal? “One hundred percent,” he says. “That’s the why of everything. Canon is cool but it’s also very limiting. I’m a fan of deconstruction. Sometimes it can be difficult to participate in deconstruction as far as beloved characters are concerned. People feel an affront.”

It’s worth noting that Snyder recently renamed his company Stone Quarry, a reference to another of his favorite books, Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. When no one will pay that book’s hero, the architect Howard Roark, to design and build to his exacting standards, he ends up working at a granite quarry.

The screen may be smaller. And Snyder acknowledges fans might watch Rebel Moon on a cell phone. But his approach to making art hasn’t changed. Snyder, a camera nerd, designed his own custom lenses to better mimic the magic of shooting on film. “Because the digital cameras are pretty cold in the way they record,” Snyder explains. “Where when you use a film camera, there is a chemical process that imbues the photography with some other alchemy that you can’t plan for. And that alchemy is that intangible thing that makes the movie have a soul. That’s what this lens’s job is. Between you and the chip, I put God.”

Says Debbie of Rebel Moon: “At his core, Zack is most fascinated with a hero’s journey and a redemptive story. What makes people do what they do? I think for him the most fascinating heroes are the ones that aren’t necessarily just good—that they might live in a gray area. That you can still be a hero without being perfect.”

I wonder if Snyder is at all relieved that DC’s beleaguered Aquaman sequel (beset by “3 reshoots, two Batmans and nonstop test screenings,” says The Hollywood Reporter) is someone else’s midnight phone call now. “Am I relieved?” he says. “Well, I get anxiety just because I know what it feels like. It’s too personal for me to feel anything like that,” adding: “The movie’s probably fine. I mean, I don’t know. Who knows?”

On the way out, Snyder takes me to his pottery studio, the one in the handsome shipping container. In a way, it’s a return to his fine-art roots—and a Zen place to put the energy that wakes him up every morning at 4:30 a.m. He shows me a shelf lined with his yet-to-be-fired coffee mugs, each stamped on the underside with the letter Z (in a font not dissimilar to the S that adorns Superman’s chest). Imperfections in pottery are part of the medium’s charm, but he’s still tinkering with the shape and size of his mugs, wanting to get the proportions and coloring just right.

Getting into ceramics was his wife’s idea. “I was playing a lot of Fortnite,” Snyder says. “I was really deep in Fortnite. Debbie was like, ‘This is no bueno.’ ” That he feels the need to add he was “winning a lot” makes me laugh, but one does not succeed in Hollywood without a competitive spirit. He concedes he was basically “addicted.” When Debbie got him some clay for his birthday, he says, “I quit cold turkey.”

Snyder fires his work here in the kiln, but he makes most of the pieces up in the house—at the dining-room table, surrounded by his family. “That way I’m not a recluse potter,” he says.

Here, he unwraps some of his latest work for me. “I made my daughter this rabbit,” he says, smiling. “I made her this hedgehog. And this bear. She was like, Can you make something for me?” As he says this, a few broken pieces tumble out of a napkin—a bespoke animal lost in transit.

“That’s liable to happen,” Snyder says. “The dangers of this work is that it falls apart. It’s fragile.”

This story originally appears in the December 2023 issue of Men’s Health.

Mickey Rapkin is a journalist and screenwriter whose first book, Pitch Perfect, inspired the film series. Previously a senior editor at GQ, he has written for The New York Times, WSJ, and National Geographic. He lives in Los Angeles.