If you purchase an independently reviewed product or service through a link on our website, we may receive an affiliate commission.

Compared with cops and superheroes, artists don’t appear on the big screen very frequently, but when they do, the results are often memorable. Dramas about art or artists can range from artist biopics to art-world satires, and as with just about any sort of story that gets the Hollywood treatment, accuracy takes a backseat to entertainment.

Still, if you’re a lover of art, there’s a lot to enjoy from this film genre, the best examples of which we’ve listed below.

-

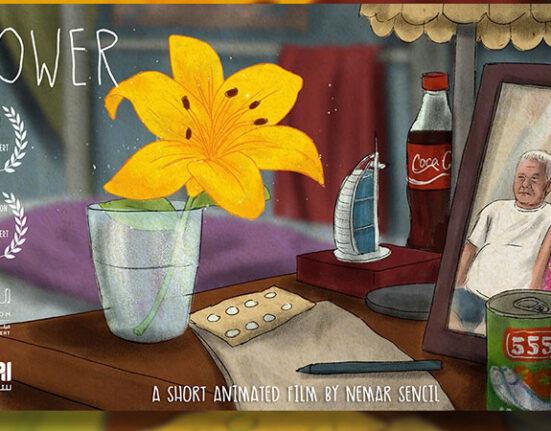

Artists and Models (1955)

Image Credit: Paramount/Getty Images. Among the directors from Old Hollywood’s studio system, Frank Tashlin is notable for being a pop-cultural deconstructionist avant la lettre. During the 1950s, he jumped from making Looney Tunes for Warner Bros. to helming live action send-ups of Tinseltown, Madison Avenue, and rock and roll. For the musical comedy Artists and Models, Tashlin teamed up with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, then working together as one of America’s most successful acts. Despite the title, Artists and Models is less about art than it is about the period’s moral panic over comic books. Martin is a struggling artist Rick who rooms with Eugene (Lewis), a comic-book nerd (likely the first appearance of the type in media history) who dreams in pulp-fiction narratives and talks about them in his sleep—allowing Rick to steal plots for his own comic book. Both the artist and the model for Eugene’s favorite comic, Bat Lady, live in the same building, and as played respectively by Dorothy Malone and Shirley MacLaine, they become love interests for the boys, with hilarity ensuing as a riot of sight gags in full Technicolor.

-

Lust for Life (1956)

Image Credit: MGM Studios/Getty Images. Several actors, including Tim Roth and Willem Dafoe, have taken on the role of the Dutch Post-Impressionist who mutilated his ear and wound up dying of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. But no one has portrayed Vincent Van Gogh with quite the same scenery-chewing panache as Kirk Douglas, who interprets him as a combustible outsider undone by his own genius. Douglas cranks his performance up to 11 in scenes such as one in which Van Gogh holds his hand above a burning candle in front of his brother Theo to demonstrate his artistic resolve. Just as volatile are the exchanges between Van Gogh and his Arles roomie, Paul Gauguin (played by the formidable Anthony Quinn). For the pivotal moment of Van Gogh’s self-disfigurement, Douglas pounds his head against a mirror while gnashing his teeth at his own reflection as the camera discretely pans away to the sound of howling. A classic of the genre, Lust for Life arguably established Van Gogh as the pop-cultural phenomenon he is today.

-

The Horse’s Mouth (1958)

Image Credit: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images. In this postwar British comedy, Sir Alec Guinness plays painter Gulley Jimson, a seedy reprobate with a lunatic commitment to his process. In the film’s central story line, he commandeers the posh London flat of the Beeders, an upper-crusty collector couple on extended holiday outside the country. Setting about to paint a large living-room mural that they never asked for, Jimson enlists a motley crew that takes up residence at the house alongside him. Meanwhile, hearing of the opportunity, Jimson’s artistic rival Abel barges in to demand a space where he can work on a sculptural commission for British Rail. Jimson refuses, but when he steps out, Abel moves in a huge marble block that crashes into the apartment below (whose occupant is also conveniently out of town), leaving a huge hole in the floor that the Beeders eventually fall through when they return home. Savagely drawn as only the Brits can, The Horse’s Mouth is satirical take on class that pits the tidiness of entitlement against the anarchy of artistic license.

-

What a Way to Go (1964)

Image Credit: Mark Kauffman/Getty Images. This mid-century romp stars Shirley MacLaine as Louisa, a four-time widow whose husbands die after becoming rich and famous with her inadvertent help. One of them, Larry (Paul Newman), is an American artist in Paris who prefers starving to selling out. He’s developed a robotic arm that paints in response to various sounds—which for Larry means banging pots, running a hammer drill, or playing bongos—to produce unmarketable results. One day, Louisa puts on a classical record to see what transpires—et voilà, the contraption produces lyrical color fields that propel Larry to art stardom. Predictably, success goes to his head: Ensconced in a chateau outside Paris, he spends his days “conducting” a small “orchestra” of machines to crank out work—that is, until they turn on him and beat him to death. The movie is surprisingly accurate in capturing the period’s nouveau réalisme milieu, with one scene featuring a woman artist shooting at a canvas strung with paint-filled balloons, an obvious nod to Niki de Saint Phalle.

-

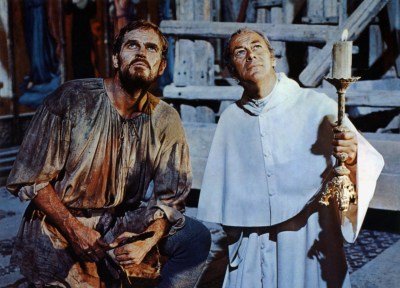

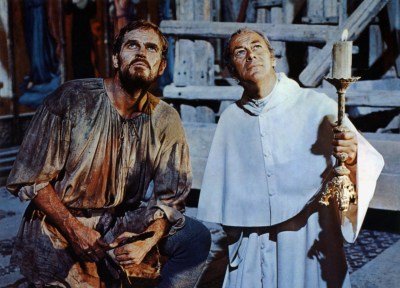

The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965)

Image Credit: FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images Chisel-jawed Hollywood legend and overly enthusiastic Second Amendment supporter Charlton Heston is probably better known for his line readings than for the movies he delivers them in. (How can one forget “You maniacs! You blew it up! Damn you! Damn you all to hell!” from Planet of The Apes?) The Agony and the Ecstasy, which portrays Michelangelo’s painting of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, is chock-full of such meaty dialog given full-throated life by Heston playing the artist opposite Rex Harrison as Sistine patron Pope Julian II. “Why do you bring fools to judge my work!” Michelangelo shouts when Julian ushers in a group of cardinals who complain that his painting contains too much nudity. Such is the agony Heston/Michelangelo endures as he labors high up on a scaffold on his back with brushes clenched between his teeth. Pure Hollywood cheese, The Agony and the Ecstasy serves up heaping helpings of costume pageantry and platitudes about art in what remains a guilty pleasure nearly six decades on.

-

Andrei Rublev (1966)

Image Credit: Everett Collection. Known for haunting narratives and surreal visuals, Andrei Tarkovsky is considered one of the greatest directors of all time. His unique approach to filmmaking colors this movie on the life of Andrei Rublev, a 15th-century Russian icon painter and revered figure in his country. Loosely based on fact, the movie transforms Rublev into an avatar of the Russian soul whose spiritual devotion marks the central role that Orthodox Church plays in shaping the national identity. Naturally this emphasis on religion got the film banned in the Soviet Union, where the promotion of atheism was state policy. Set amidst a turbulent period of internecine warfare and Tatar invasion, Rublev is sweeping in scale, with epic battles serving as background to Tarkovsky’s tale of a wandering monk seeking artistic freedom. The story is divided into eight episodes bookended with a prologue and an epilogue that includes a fanciful, anachronistic scene of a hot-air balloon ride 300 years before they were invented.

-

Camille Claudel (1988)

Image Credit: Copyright © Orion. Courtesy of Everett Collection. Until recently, women in art history were underrepresented—if not invisible—compared with men, and many of those who were recognized stood in the shadows of husbands or lovers who happened to be famous artists. Such was the case with Camille Claudel, a 19th-century sculptor who was the mistress, model, and occasional collaborator of Auguste Rodin. Born into a devout Catholic family, Claudel (Isabelle Adjani) struggled with her strict upbringing as well as with the expectations of what a women’s role was supposed to be. She insisted on having the same freedom as men in pursuing her ambitions and conducting her personal affairs. Claudel’s involvement with the married Rodin (Gérard Depardieu) did afford her some success; however, his wandering eye ended their relationship, and over time she became paranoid and unsure of her talent—even to the point of destroying her work. Eventually she was confined to a mental asylum despite her protestations that she was sane. The film garnered two Oscar nominations, including one for Adjani.

-

My Left Foot (1989)

Image Credit: Copyright © Miramax. Courtesy Everett Collection. Daniel Day-Lewis won the first of his best actor Oscars for his portrayal of Irish artist Christy Brown, who, as a child, developed cerebral palsy. As the title suggests, he painted with his left foot because it was the only appendage he could control. It was a demanding role, one to which Day-Lewis applied the uncompromising approach of method acting. He insisted on staying in character during the production of the film to the point of having the crew move him around in a wheelchair, lifting him over obstacles when needed, and feeding him his meals. One thing Lewis couldn’t do was paint with his left foot; he had to use his right one, necessitating the use of a mirror to shoot certain scenes. Though the movie provided its share of lighter moments, Lewis’s verisimilitude heightened the inherently dramatic nature of Brown’s personal triumph over impossible odds.

-

Surviving Picasso (1996)

Image Credit: Getty Images. These days Picasso’s toxic masculinity often supersedes his work in public discourse, and deservedly so. He divided women into two categories: doormats to be used and discarded, and goddesses to be elevated on pedestals—until, that is, they too become doormats to be used and discarded. Among the emotional roadkill Picasso left behind, only one person, according to this Merchant-Ivory production, stood up to his abuse: Françoise Gilot. Based on the book by Arianna Huffington, Surviving Picasso is told from the perspective of Gilot (Natascha McElhone, playing opposite Anthony Hopkins as Picasso), and while we see her refusing to completely give into Picasso’s manipulative charms, the film would be nothing without his charismatic, preternatural self-absorption and careless disregard for everyone else. Interestingly, the film starts with Picasso riding out World War II in Nazi-occupied Paris, the only place and time, perhaps, in which he was genuinely obliged to worry about what other people—i.e., the Gestapo—thought. Still, the film portrays him cavalierly dismissing their presence. The estates of both Gilot and Picasso refused to help in the making of the film, limiting its ability to portray Picasso’s work in full.

-

Artemisia (1997)

Image Credit: Copyright © Miramax. Courtesy Everett Collection. This biopic of painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1656), treats its subject as a proto-feminist. The daughter of the Italian Mannerist Orazio Gentileschi, Artemisia, played by Italian actress Valentina Cervi, was born in Rome, and though she wasn’t allowed a formal art education due to her gender, she was given the run of Orazio’s studio, where she learned how to draw, mix color, and paint. She was tutored in perspective by an older artist, Agostino Tassi, who sexually assaulted her at age 17, after which they continued their relationship. The film centers on Orazio’s discovery of their liaison and his suit against Tassi for rape. Unfortunately, the subsequent proceedings put Artemisia’s own reputation on trial: To determine whether she was telling the truth or not, Gentileschi was forcibly given a pelvic exam before the court and was tortured by having her fingers painfully yanked apart with cords tied around them. Nevertheless, the artist insisted that her affair with Tassi was consensual, a point that Artemisia focuses on as evidence of a modern woman asserting her agency in the face of male privilege.

-

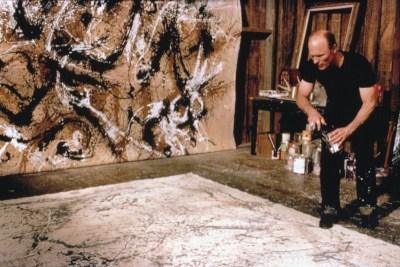

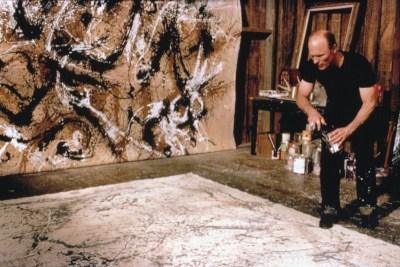

Pollock (2000)

Image Credit: Copyright © Sony Pictures Classics. Courtesy Everett Collection. Ed Harris’s portrayal of Abstract Expressionism’s most famous figure nabbed him an Oscar nomination for best actor. Pollock is faithful to the artist’s life—which, given his troubles with alcohol and inner demons (which may have included having one foot in the closet), was eminently suitable for dramatization. In his directorial debut, Harris accurately evokes the New York art world of the 1940s and ’50s and players such as art talent scout Howard Putzel (Bud Cort) and critic Clement Greenberg (Jeffery Tambor), who first championed Pollock before dismissing him as yesterday’s news. Just as important are the women in his life: his wife, the painter Lee Krasner (Marcia Gay Harden, an Oscar winner for the role); and his patron Peggy Guggenheim (Amy Madigan, Harris’s wife offscreen), who elevated Pollock from an indigent paying for his groceries with paintings to art star appearing in the pages of Life magazine. Also notable is the remarkable physical resemblance between Pollock and Harris, who enlivened his performance by learning to paint like his subject.

-

Girl With a Pearl Earring (2003)

Image Credit: Copyright © Pathé International. This movie, starring Scarlett Johansson and Colin Firth, attempts to address one of art history’s most enduring mysteries: Just who was the model for Johannes Vermeer’s 1665 masterpiece, Girl with a Pearl Earring? The film, based on the best seller by Tracy Chevalier, proposes that she was a household maid named Griet (Johansson) working for Vermeer (Firth). Moreover, the story is charged not only by the ambiguous sexual tension between Griet and her employer, but also by the growing attraction between her and Pieter, the local butcher’s son (Cillian Murphy). In the meantime, Vermeer’s most important patron, Van Ruijven (Tom Wilkinson), has designs on her and attempts to rape her after Vermeer refuses to sign Griet over to the service of Van Ruijven, who has a reputation for humping the help. Beautifully shot to echo Vermeer’s aesthetic, Girl is a sort of deeply repressed bodice ripper offering answers to questions (such as the origin of the eponymous earring) that never needed to be asked in the first place.

-

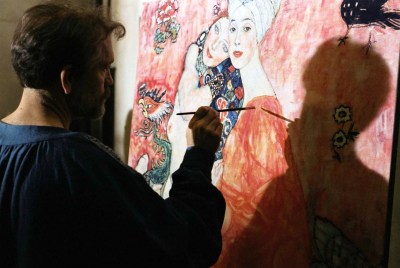

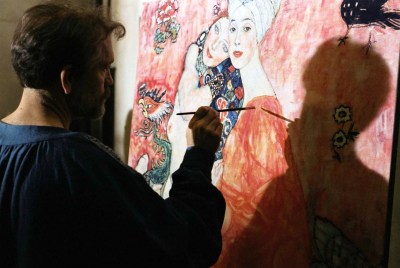

Klimt (2006)

Image Credit: Copyright © Outsider Pictures. Courtesy Everett Collection. It’s hard to say why fin de siècle Vienna was a hotbed of psychosexual currents, except, perhaps, that it was the seat of a decrepit empire sitting atop a volcano of clashing ethnicities haphazardly lumped under its banner. Vienna was where Sigmund Freud formulated his theories on the subconscious, Gustave Mahler composed emotionally dissonant symphonic mashups, and Egon Schiele created overtly erotic images bordering on the obscene. Then there was Gustav Klimt, played here by John Malkovich in fine, being-John-Malkovich form. Historically, Klimt was cofounder of the Viennese Secession, but Klimt is primarily interested in its subject’s sex life, told here in randomly ordered flashbacks as an older Klimt lies in a hospital undergoing mercury treatment for advanced syphilis. We learn of his many mistresses and illegitimate children, known and unknown, including one daughter working in a brothel he frequented. Klimt is a mix of period costume and scenery mastication in which the art is less important than the over-the-top drama.

-

Seraphine (2008)

Image Credit: Courtesy of TS Productions. This French production relates the true-life tale of Séraphine Louis (Yolande Moreau), a middle-aged housekeeper turned self-taught artist. Inspired by her faith and the stained-glass windows of her local cathedral, she begins to produce primitivistic floral studies and still lifes bordering on the hallucinogenic. They attract the attention of a noted German art critic and collector named Wilhelm Uhde (Ulrich Tukur), who encourages Séraphine despite her protestations that she’s only a humble domestic. Forced to leave France at the onset of the World War I, Uhde returns in 1927 and starts to buy and sell Séraphine’s work, providing her a stipend with the proceeds. Her newfound renown, however, upends Séraphine’s emotional equilibrium: She buys herself a bridal gown, despite having no prospects for marriage, and begins wearing it around town, arousing suspicions about her mental state. The Depression ends her career, and Séraphine finds herself institutionalized for her erratic behavior. The film offers lush scenes of Séraphine communing with nature while pondering the difficulties of an outsider becoming an insider, however briefly.

-

Mr. Turner (2014)

Image Credit: Simon Mein. Copyright © Sony Pictures Classics. Courtesy Everett Collection. While his art-historical reputation is hardly unknown outside the United Kingdom, J. M. W. Turner is considered a national hero in Britain. This biopic stars Harry Potter actor Timothy Spall playing with gruff gusto the role of the boundary-pushing painter during the final 25 years of his life (a star turn that won Spall best actor laurels at Cannes). We see him grapple with the death of the father he adored, as well as his (sometimes sexual) relationship with his housekeeper, Hannah Danby, and his furtive romance with the landlady of his seaside cottage, Mrs. Booth. The film depicts his competitiveness in a pivotal scene set during the British Royal Academy salon of 1832: Turner, noticing how much more muted a seascape of his seems compared with a landscape next to it by John Constable, decides on the spot to one-up his rival by adding a splotch of bright red paint to his work, masterfully transforming into a buoy bobbing in the foreground waves.

-

Big Eyes (2014)

Image Credit: Leah Gallo. Copyright © Weinstein Company. Courtesy Everett Collection. Tim Burton specializes in outsider-y characters, whether imagined (Edward Scissorhands) or real (Plan 9 From Outer Space auteur Ed Wood), so Big Eyes, the strange, true-life tale behind those ubiquitous kitsch portraits of children with the eponymous features, seems made to order. The plot revolves around Margaret Keane (Amy Adams), the originator of the paintings, and her husband, Walter (Christoph Waltz), who took credit for them. Walter is peddling cheesy Parisian streets scenes by another artist as his own work when he meets Margaret. Pulling the same stunt with her, he puts her images on posters, plates, cups, and other tchotchkes, which sell like hotcakes. Margaret goes along with the scheme initially until she discovers Walter’s original ruse and tells him she wants out; he threatens to kill her, almost setting their house on fire. Margaret flees for Hawaii, exposes Walter, then sues him for defamation when he tells a newspaper that she’s delusional. In one of the film’s funniest scenes, Walter, acting as his own attorney, cross-examines himself during the trial. The story of Big Eyes is so absurd that only someone like Burton could do it justice.

-

The Monuments Men (2014)

Image Credit: Claudette Barius. Copyright © Sony Pictures. Courtesy Everett Collection. While Woman in Gold deals with a specific example of Nazi-looted art, this film involves the Third Reich’s wholesale theft of art-historical treasures. George Clooney leads an all-star cast in this true-life account of a U.S. Army unit of art specialists set up the during the closing months of World War II to track down and recover artworks stolen by the Germans. The scale of the larceny was breathtaking, with iconic paintings, sculptures, and altarpieces pilfered to stock the collections of senior Nazis like Hermann Goering, as well as a Führermuseum planned for Hitler’s hometown of Linz, Austria. With the noose tightening around the Reich, most of these works were spirited underground in various tunnels and abandoned mines. Because American officers on the front didn’t want to risk their G.I.s going after art, the Monuments Men had to work without backup. Featuring breezy repartee between Clooney and costars such as Matt Damon, Bill Murray, and John Goodman, the film concludes with a dramatic race against time as our boys pack up a cache of works while a unit of the Russian Army out for spoils bears down on them.

-

Woman in Gold (2015)

Image Credit: Robert Viglasky. Copyright ©Weinstein Company. Courtesy Everett Collection. A more sober consideration of Klimt’s legacy, Woman in Gold dramatizes the recovery of the artist’s masterpiece, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), 60 years after it was looted by the Nazis. The plot follows the subject’s niece, Maria Altmann (Helen Mirren), during her seven-year legal battle against the Austrian government, which had dubiously gained possession of the painting following the Nazi Anschluss. Commissioned in 1903 by Adele’s husband, Ferdinand, a wealthy Viennese-Jewish businessman, the portrait earned the sobriquet “the Mona Lisa of Austria.” In 1941, Nazi confiscated the picture along with Bloch-Bauer’s other assets under bogus tax evasion charges (though by then he’d already fled Austria). Before that, however, Adele, who died in 1925, had willed the painting to Vienna’s Belvedere Museum, which cited her bequest in its claim to ownership. Altmann’s suit, which she filed in U.S Federal Court, contended that the painting was never Adele’s to give, since it belonged to her husband, and that in any case the Belvedere acquired Portrait of Adele by purchasing it from the Nazis. Eventually the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Altmann’s favor. In 2006, Austria finally returned the painting, which Altmann sold to Ronald Lauder’s Neue Galerie in New York for a then-record $135 million.

-

Egon Schiele: Death and the Maiden (2016)

Image Credit: Copyright © Novotny & Novotny Film Production, Amour Fou Luxembourg. Like Klimt himself, his contemporary Egon Schiele has gained legendary status in the public mind, so it stands to reason that he, too, would become the subject of a biopic—one in which Klimt plays a vital role as Schiele’s supporter and defender. An Austrian/Luxembourger coproduction, this German-language film revolves around Schiele’s two muses and models: his sister Gerti (who poses for her brother in the nude), and Wally, a woman who had modeled for Klimt and was eventually immortalized by Schiele in the eponymous painting from 1915. A torrid romance develops between artist and model (though Schiele was involved with other women at the time, including his fiancée). Schiele also uses other underage models, something his nosy neighbors notice and report to the police. He’s put on trial for lewd behavior with minors, but a shrewd lawyer, retained by Klimt, gets the case dismissed by proving that the girls’ maidenly virtues are intact. Like the Klimt movie, Death and the Maiden sensationalizes its story, but considering its subject, how could it not?

-

Final Portrait (2017)

Image Credit: Parisa Taghizadeh. Copyright © Sony Pictures Classics. Courtesy Everett Collection. Australian actor Geoffrey Rush plays the Swiss-Italian modernist Alberto Giacometti in this film written and directed by actor Stanley Tucci. The story revolves around Giacometti’s interaction with James Lord (Armie Hammer), an American critic whose memoir served as the basis for this adaptation. Visiting Paris, Lord drops in on Giacometti’s ramshackle studio, where the artist asks him to sit for a portrait. Flattered, Lord agrees, and while the talkative and disheveled Giacometti assures him the sitting will take two days at most, it goes on for three weeks—plenty of time to examine various relationship conflicts, including Giacometti’s strained marriage and his imprudent relationship with a prostitute. Lord grows increasingly restless and inconvenienced as Giacometti keeps painting out the previous day’s work and starts over again. Rush plays Giacometti as a genius crippled by self-doubts despite his success; he also bears a surprising resemblance to the artist, much as Harris does in Pollock.

-

The Square (2017)

Image Credit: Copyright © Magnolia Pictures. Courtesy Everett Collection. This European black comedy takes a gimlet-eyed look at several hot-button cultural issues, including social media, immigration, and the corporatization of art. Christian (Claes Bang), a museum curator in Stockholm, has his hands full: He’s just had casual sex with a journalist (Elisabeth Moss) whose name he can’t remember; his wallet and cell phone are stolen and subsequently recovered (which involves a package drop-off at a 7-Eleven and a later confrontation with an Arab kid whose family accuses him of being a thief); and finally, there’s the opening of an outdoor installation called The Square—an illuminated quadrangle sunk into the museum’s courtyard, which serves as “sanctuary of trust and caring.” This isn’t considered sexy enough for the PR firm hired to promote the show, so they post a clip to YouTube of a fake terrorist attack on the piece to gin up interest. Another sequence involves a dinner gala being terrorized by a muscled, shirtless performance artist running amok while making ape noises. Is making fun of contemporary art a bit like shooting fish in a barrel? Absolutely, but The Square does it with style.

-

The Electrical Life of Louis Wain (2021)

Image Credit: Jaap Buitendijk. Copyright © Amazon Studios. Courtesy Everett Collection. The movie stars Benedict Cumberbatch as the Victorian artist Louis Wain, whose work is better known for being reproduced in texts about psychosis than for being hung in museums. Wain was a successful commercial illustrator and children’s book author who began a descent into mental illness after the death of his wife from breast cancer. Near the end of her life, Wain began drawing his wife’s pet cat, Peter, to comfort her. After she died, Peter became Wain’s principal model, whose depiction through the years changed from naturalistic to almost unrecognizably distorted, marking Wain’s mental decline (hence the psychological field’s interest in his work). Although Wain’s story didn’t end well (he was confined to a series of hospitals as his behavior grew more erratic and violent), the film treats the tale with a certain whimsy, at least during its first part, a tone underscored by Cumberbatch’s portrayal of him as an eccentric outsider, the sort of role for which the actor is known.