After the Great Migration saw African Americans relocate in high numbers to northern cities to escape racist oppression, 1920s Harlem, New York became a mecca for Black creativity in visual, literary and performing arts. The Harlem Renaissance was rooted in countering racial stereotypes and prejudices through Black self-representation and the movement left a significant and lasting impact on the arts.

The visual artists of the Harlem Renaissance were a dynamic collective, drawing upon African aesthetic legacies to portray Black subjects in a sensitive and modern manner. Below are five artists whose works played a role in reclaiming Black identity during the Harlem Renaissance.

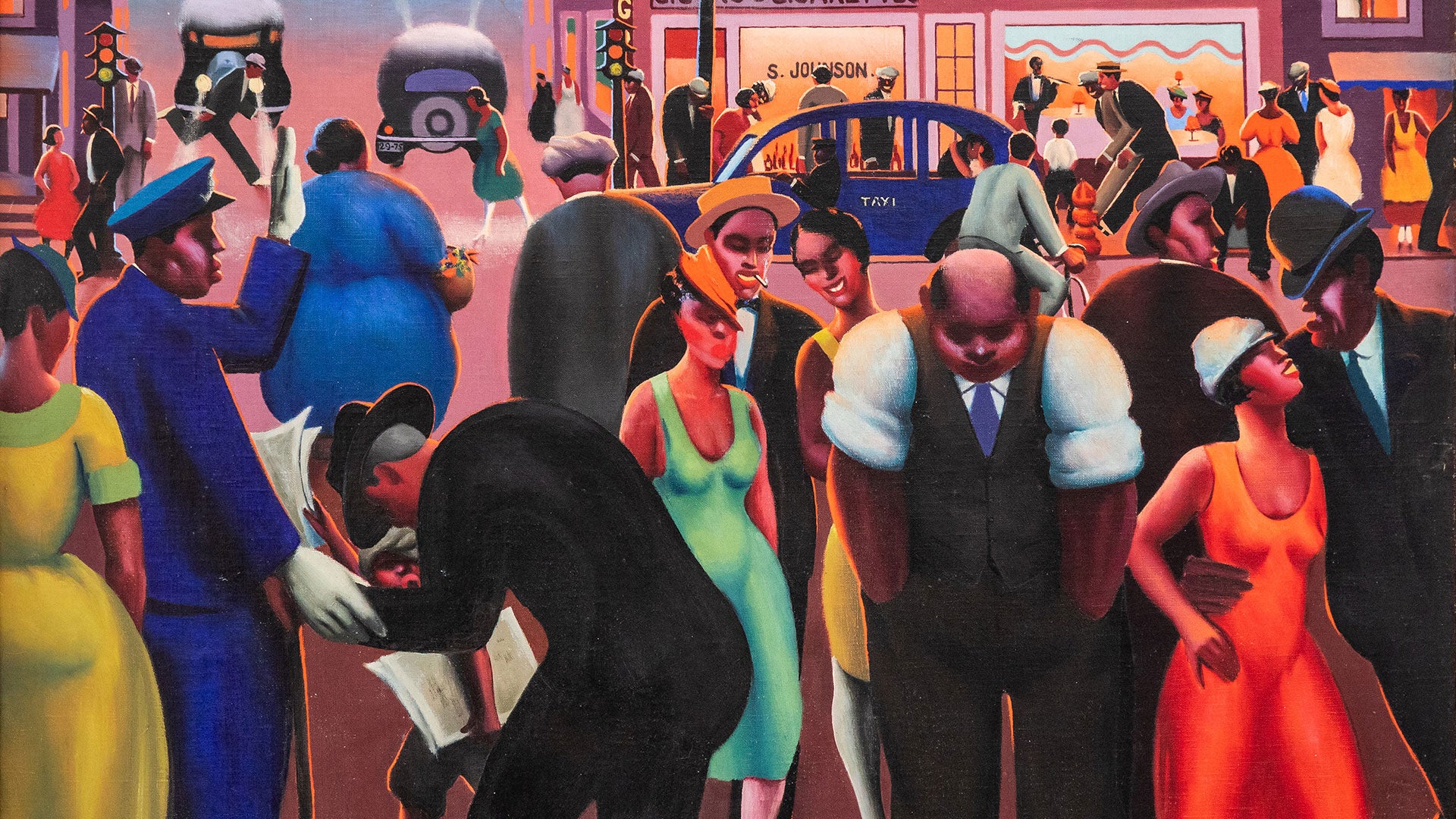

1. Aaron Douglas

A segment from a 1934 mural by Aaron Douglas titled, ‘Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery to Reconstruction.’

Aaron Douglas witnessed Harlem’s outpouring of artistic and literary activity while stopping in New York in 1925 on his way to Paris. Drawn by he vibrancy of Harlem’s art scene, he decided to stay awhile. Curator and art historian Caroline Goeser writes that, while in Harlem, Douglas studied with German expatriate artist Winold Reiss “who urged him to emulate African art in his work.” With his encouragement, Douglas drew upon African and American aesthetics to develop his unique visual language, creating illustrations for publications as well as large-scale multi-paneled murals.

“Douglas often made reference to ancient Egypt in his illustrations, in the form of pyramids but also stylistically, imbuing his figures with composite forms (bodies seen frontally and heads in profile), as in ancient Egyptian wall paintings,” Goeser notes. “These were visual strategies that connected contemporary Black figures with the Ancient civilization of Egypt, a powerful act of reclamation that flew in the face of demeaning 1920s stereotypes in white publications that characterized Black identity as ‘primitive.’”

Considered among the signature artists of the Harlem Renaissance, Douglas referenced the past and embodied the future. He drew upon tenets of African art as much as he did Cubism and Art Deco, using geometric and layered forms to render stylized scenes.

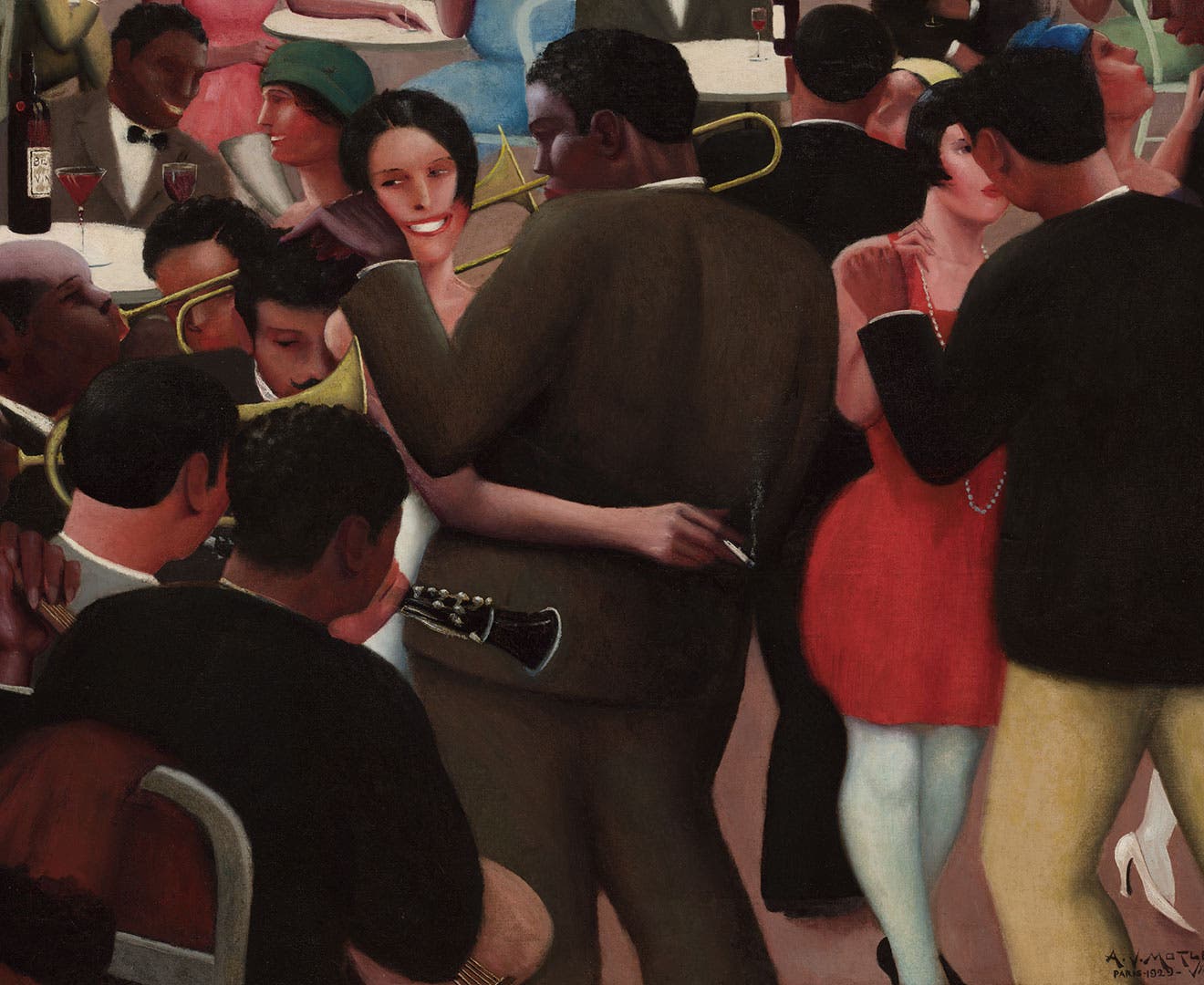

2. Archibald Motley

The 1929 painting, ‘blues,’ by Archibald J. Motley, Jr.

Archibald Motley, known as a Jazz Age Modernist, captured the dynamism of the Roaring Twenties through vibrant nightlife scenes and the portraits.

Although Motley was based in Chicago, he was deeply in dialogue with the artistic, literary and cultural scene in Harlem. He read W.E.B. DuBois and Alain Locke, both significant Harlem Renaissance thinkers and writers, and participated in exhibitions in New York.

In 1918, the same year he graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Motley published “The Negro in Art,” an essay on the difficulties Black artists faced in The Chicago Defender. His artistic output was grounded in the idea that art could act as a force to help end racial prejudice. Motley, who had multiracial heritage, painted figures with a variety of skin tones, revealing his personal interest in portraying the multiplicity of Blackness.

Motley mainly painted portraits throughout the 1920s, participating in exhibitions in Chicago and New York and winning a Guggenheim fellowship which enabled his yearlong independent study in Paris in 1929. Motley’s Paris paintings saw a shift from portraiture as he composed vibrant group scenes of dance and music in the environment of the modern city.

His Jazz Age scenes depicted the African American, West Indian and African expatriate frequenters of Parisian clubs. He animated his paintings with a sense of movement and infused his works with warm variations in skin tone, lamp light and the dark, deep hues of blue and black to paint the night.

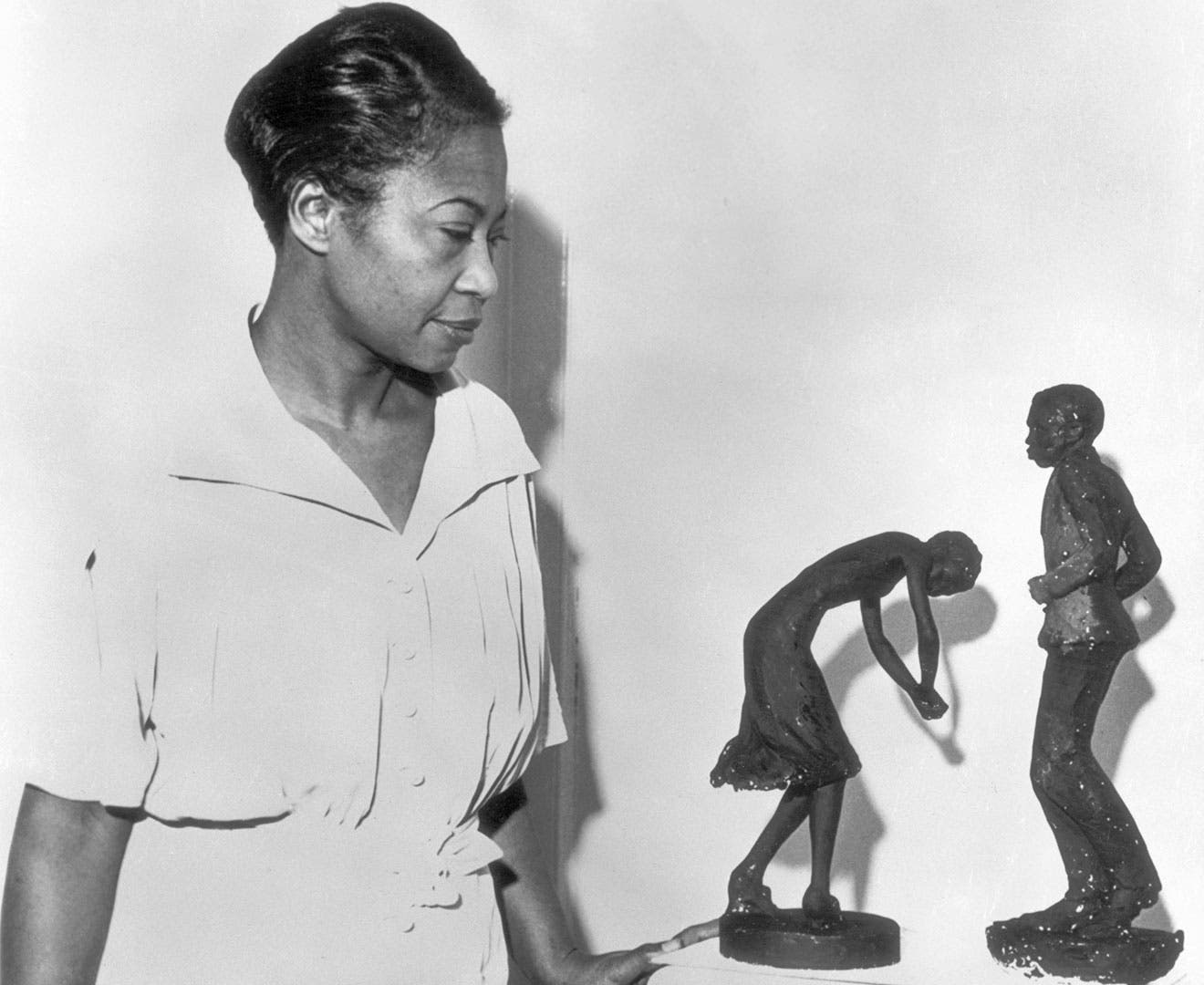

3. Augusta Savage

Augusta Savage with two of her sculptures, 1937.

Augusta Savage overcame a difficult childhood under strict, religious parents who condemned her interest in sculpture, to become a leading artist of the Harlem Renaissance.

Savage made her way north from Florida to New York in 1921 and earned a scholarship to attend art school. During her studies at the Cooper Union, Savage often visited the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library, where she studied African art and culture. The library commissioned her to create a sculpture of W.E.B. DuBois, and she went on to sculpt portraits of other notable community members, becoming increasingly enmeshed in Harlem’s flourishing creative community.

In this environment, Savage created some of her most seminal sculptures. Her work was greeted with acclaim: Head of a Negro won the Otto Kahn Prize at the Harmon Foundation in 1928, and a photograph of Gamin (1929), a sympathetic portrayal of a young working-class Black boy with thoughtful expression, appeared on the cover of Opportunity magazine.

After studying at Paris’ Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Savage returned to Harlem in 1932. She was elected to the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors in 1934, worked as an art teacher at the Harlem library, and opened her own studio. Granted funding by the Works Progress Administration, Savage established the Harlem Artists Guild, the Harlem Art Workshop, and the Harlem Community Artist Center, encouraging her students to create works that reflected their African American identity.

4. James Van Der Zee

A portrait by James Van Der Zee of activist Marcus Garvey in military uniform during a Universal Negro Improvement Association parade in Harlem, New York City, 1924.

James Van Der Zee captured life in Harlem through portraiture for decades at Guarantee Photo Studio, which he opened in 1917. Sought out by residents of the neighborhood as the photographer for special occasions such as weddings and funerals, as well as formal portraiture, Van Der Zee shot hundreds of photographs of Harlem’s growing middle class. His works captured the neighborhood’s celebrities and cultural leaders, such as activist Marcus Garvey, dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and poet Countee Cullen.

Van Der Zee brought an element of artistry to bear on his photography, meticulously staging and reworking his images to create ideal representations of his subjects. He often set his studio portraits against ornate backdrops, incorporated props into the scene, and costumed his sitters to imbue his subjects with glamor. Van Der Zee also manipulated images as they appeared on the photographs’ negatives, adding elements by hand and superimposing other photographs through combination printing to create new images.

“As an artist, Van Der Zee […] actively fashioned his photos to tell the stories he wanted to,” author Lara Antal explains in her book about the photographer. Van Der Zee himself famously said, “I put my heart and soul into them and tried to see that every picture was better-looking than the person.”

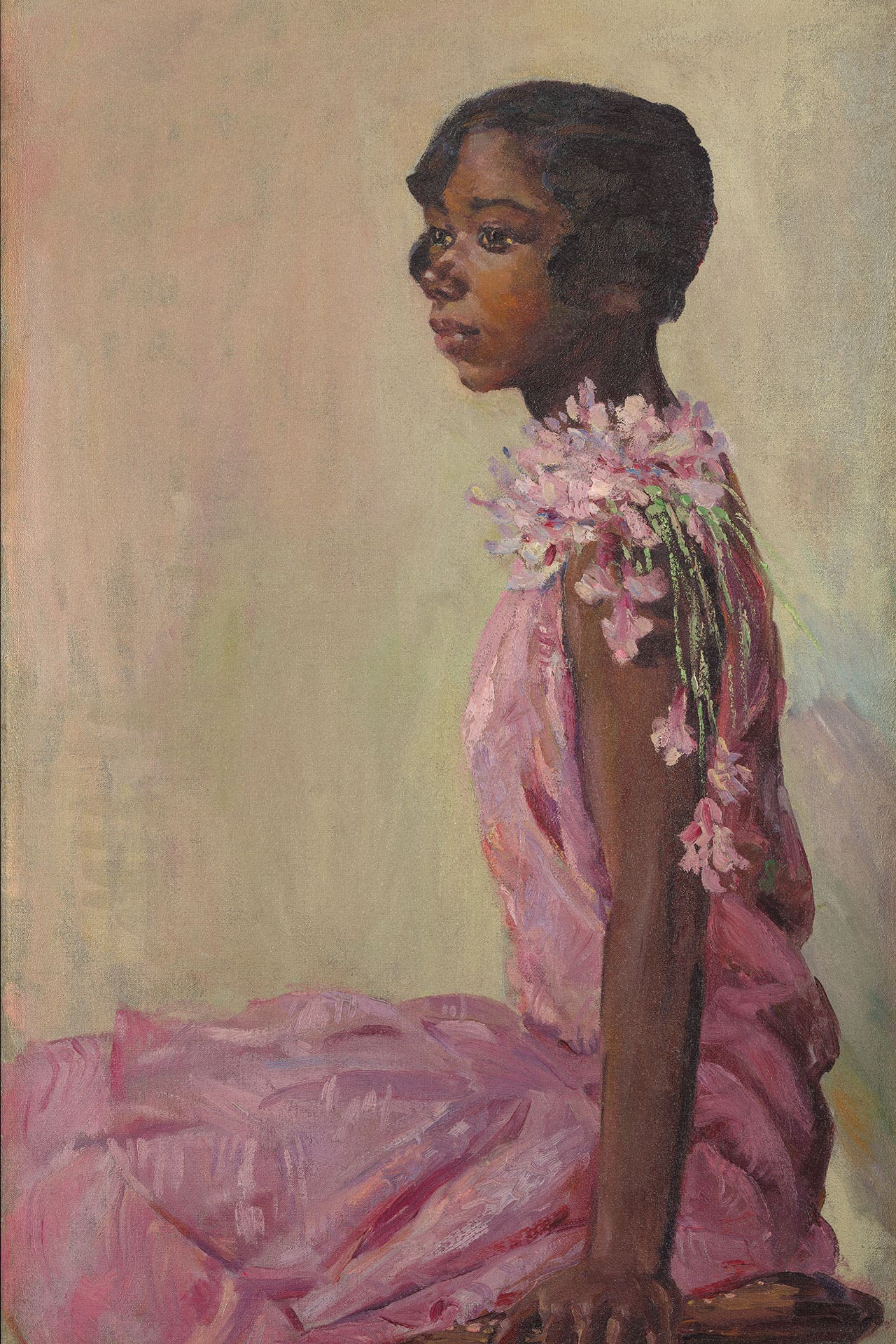

5. Laura Wheeler Waring

‘Girl in Pink Dress,’ by Laura Wheeler Waring.

Laura Wheeler Waring studied drawing, painting and portraiture at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, gaining an affinity for Impressionist art. Upon graduating in 1915, Waring was awarded a scholarship to travel to Europe where she attended the Académie de la Grande Chaumière until World War I interrupted her studies. During her time abroad, she studied the works of modernists Cezanne, Monet and Manet, which would influence her own artistic style.

In her paintings, Waring made use of brilliant color and loose brushwork to render diffuse atmospheres inhabited by stylish subjects. Art historian Lisa E. Farrington describes Waring’s paintings as “paradigmatic of the images of upscale [B]lacks that marked the Harlem Renaissance.”

In this manner, Waring’s portraits offered dignified and elegant portrayals of Black individuals, painting a sensitive picture of society through an elevated visual language. Waring’s approach drew commissions for a series of portraits of notable African Americans, including W.E.B. DuBois, James Weldon Johnson, George Washington Carver and Marian Anderson.

“The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” is on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art from February 25 through July 28, 2024.