Artist Chloê Langford discusses turning video games into performances, letting multiple contradictions exist, and exploring what’s desirable about our culture of overstimulation.

What is your creative practice?

I make performances and video games, and sometimes websites. I’m in a collective called Fantasia Malware. There’s three of us, and we create games and performances.

When I saw Fantasia Malware perform it was the first time I’d ever seen a video game be combined with a performance, which was a really unique experience for me. Can you tell me more about the collective?

The three of us used to be in a bigger collective made up of 10 people, but the collective ended because of some disagreements. Jira, Gabriel, and I wanted to keep co-creating so Fantasia Malware took off very quickly. As a smaller collective we felt more focused and our goals more aligned.

What made you combine game making with performing?

We started doing performances for several reasons: we formed around the time of the pandemic so it was this moment in time where suddenly everyone was making digital art, and digital art was much more in focus than it was before…but for people like us who’d already been doing that for a while it was kind of weird and frustrating. We realized we actually wanted to do things in real spaces with real people. Releasing things online can be a little bit like shouting into the void. We did a few online performances during the pandemic, and then we were like, “Actually, we want to do this in person.”

While we were still in the bigger collective we released a game and had a launch party for the game and did a live play through. We didn’t intend for people to sit and watch the whole thing, but people were surprisingly into it, and actually sat and watched for several hours. We were like, “Oh, people are interested in this thing that we have made.” It’s nice to act it out live, to play the video game in front of other people and feel that something is happening together in the room. Kind of like performing a song live instead of only releasing it online. And so we wanted to do more with that.

Can you tell me about a recent performance you guys put on?

Our most recent one is called Sex! At Alexanderplatz. The game is actually designed to be a performance, but you can also download it and play it alone. Normally you design video games to be played by someone else. But since we wanted to do performances we are designing games to be played by us on stage in front of a live audience. We sort of become tools inside of the game, or non-player characters who are being controlled by the game in some sense—I don’t mean that super literally. It’s not like every single thing we do is controlled by the game, but what we say or how we act is sort of built into the story of the game.

For me, because I’m also not in this video game world at all, watching your performance was super unique. You guys are wearing costumes, are surrounded by props, the audience can watch the video game being played by the person on stage and also watch the person playing who is a character in the video game come to life. I know there’s a huge online scene of people watching other people play games but it’s just that…watching someone play a game and not be part of the game.

Exactly, though our idea was a bit related to this. The first performance we ever did was on Twitch during the pandemic. I guess seeing people play other people’s games made us think, “What if we made games where we’re kind of seeing streaming as the outcome rather than someone else playing the game?” So we’re kind of building a system for us to interact with, for other people to watch us interact, and other people watch us interact with this system.

It doesn’t necessarily take away the interactivity of a game, but it puts it in a different place. Usually the player would interact with the game, and in this case, we are interacting with a system we are building.

When you’re designing the game, you’re already planning in the character that’s going to be on stage playing the game?

Yes, so in the performance/game Sex! At Alexanderplatz there’s a lever the size of a person topped with a giant butt plug on stage. It’s a dating game and each character, played by the three of us, takes turns trying to find the love of their life. They find dates using an app that functions like a slot machine. One of us will pull this giant butt plug lever on stage and it’ll make this crazy slot machine behind us on the screen spin, we press a button to stop it and dating profiles will appear. There’s this idea that we’re these miniature people in this big system that we’ve created to drive our actions on stage.

Are there topics your collective explores again and again?

We don’t necessarily deliberately always focus on one theme. I think things come up again because they are our common interests, our common concerns, but it’s important for us to stay open and to make work about what feels right to us in the moment.

There are multiple contradictory voices coexisting, and that’s part of collaborating and working collectively. We try to accommodate our different voices as individual artists, but in way that doesn’t need us all to agree with one another. We don’t try to make it as though there’s one singular voice in the work, we want our different personalities to shine through. I do think overstimulation, intensity and chaos are topics that come up often.

What is it about overstimulation that interests you?

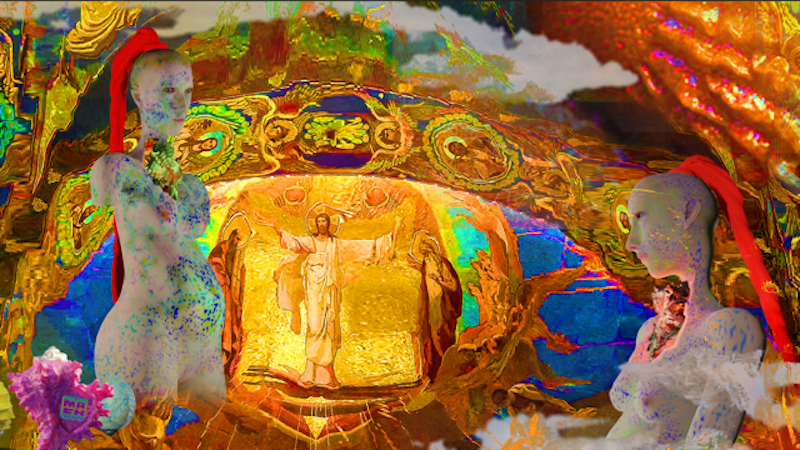

Digital culture often deliberately tries to manipulate people’s attention. We are instinctively drawn to a sense of relentless overstimulation. It’s interesting to me to explore this tendency in our culture right now, and our tendency to be exploited for our desire for stimulation.

It’s interesting to explore the desire itself and the thing that can be manipulated, the thing that makes us vulnerable to manipulation. It’s interesting to explore what’s pleasurable about those things, and also to kind of warp it or play with it in a way that makes it more visible to yourself—almost overexposing or dramatizing it even.

I also wouldn’t say that we have a clear stance on this topic, but it’s rather a genuine exploration of our feelings about these things and our desire to work with these aesthetics, or these interaction tactics. I think it’s maybe a more honest way to explore this part of culture right now rather than only coming from a quite critical, potentially a little bit dogmatic or didactic point of view.

Ultimately I think this hyper stimulated culture exists because we’ve created it.

{And there’s obviously a huge difference to you as an art collective playing with this attention economy or a multi-billion social media platform doing it. Do you also make games on your own?

So, actually as a collective, we do two things. One is that we make work together, and this is often the work that gets the most publicity but we also publish our solo work under the Fantasia Malware name as a game label.

So, it’s both a collective and a label, kind of like a music label where people publish their own releases, but all under a collective label name. We do this because we are stronger together than separately, we have more resources, we have more [of a] reputation. I mean, we’re not massively famous or anything, but whatever small reputation we have built, we can also use to push forward our own individual work.

And so it’s a way of making the collective work for us, what we are doing together should also support our individual work.

What’s the process behind the three of you creating a game together?

It depends a bit on the project, of course, but with SEX! At Alexanderplatz, we had wanted to make a dating game for a long time. We wanted a game where people simulate going on dates. We shared all our ideas and came up with some really ridiculous stuff. And then over the process of several months kind of built a world or a game around that. We share ideas but then each of us interprets the idea in different ways and sometimes we will realize that we’ve misunderstood each other. And then we have to recrystallize the idea over and over again through conversations about how we imagine the game’s world to function. We have a process of rewriting and rewriting to build relationships between what we’re doing, so that our ideas exist in the same universe, but still have their own identities.

You also make games on your own. Are you ever worried that your individual style as a game designer has become super intermeshed with the collective’s style?

I don’t think so. The thing I’m worried about more is I need to put more energy and intention into the things that I make on my own. But it’s not so much that I worry about the ownership or individual fingerprint of a certain aesthetic. I think it’s okay if there’s overlaps between our individual practices and what we do together. I don’t feel that I need to have a sense of ownership over things that have come from me, that have come into the collective and been shared amongst us.

How do you feel about your work being shown in gallery or art spaces?

Although we are kind of moving in art world spaces or circles we are mostly not working in museums. I guess we’ve worked a lot in this kind of crossover space between art and gaming. I think the reason that we’ve gravitated towards performance as well is, we are interested in the space between the art world and the video game world. Neither world is very satisfying on its own for us so we take the bits that are interesting to us and throw away the rest.

But the reason that we’ve gravitated more towards performance is we think that video games are inherently more suited to performance than to being exhibited in gallery spaces. That doesn’t mean they can’t be exhibited in gallery spaces in ways that are successful, but I do think it’s quite difficult, and there’re a lot of issues with doing so. For example, a lot of people are not super video game literate, like using controls and things are sometimes intimidating for people. And then to do that in a gallery space can feel a bit exposing, and people feel uncomfortable.

And so for us, performance is a way that we can skip a lot of these issues and kind of create a new medium or a new format, rather than trying to shove one format inside another.