When Abbot Kobori Geppo of Daitokuji Ryokoin Zen Temple in Kyoto, Japan visited the Asian Art Museum in 2017, he spontaneously offered to lend two of the most famous Chinese ink paintings in the world for the very first time in their 800-year history — with the hope that they might cultivate empathy.

“We were obviously quite surprised,” curator Yuki Morishima told the Chronicle. “We were simply just chatting in the lobby and he suggested to share the paintings with the people of San Francisco.”

Those two paintings, “Persimmons” (widely known as “Six Persimmons”) and “Chestnuts,” comprise the Asian Art Museum’s “The Heart of Zen” exhibition, on view through Dec. 31. They are being displayed one at a time for a three-week period each to protect the Song dynasty artworks from excess light exposure. The two hanging scroll paintings can be seen together for just one weekend, Dec. 8-10, when Abbot Geppo is scheduled to lead meditation sessions and serve tea.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Museum officials are calling the chance to see these paintings a “once-in-a-lifetime” opportunity, but that’s likely an understatement.

The Ryokoin Temple, which is closed to the public, has held the paintings since they were donated by the family of Tsuda Sogyu shortly after the merchant’s death in 1591. Sogyu, a famous tea practitioner, had imported the paintings from China. Since then, neither painting has ever left Japan.

Originally painted by the 13th-century Buddhist monk Muqi (also known as Muxi, Fachang and Mokkei Hojo) as handscrolls meant to be viewed by one or two people at a time, “Persimmons” and “Chestnuts” were remounted as hanging scrolls in Japan. At the Ryokoin Temple, they were hung in the tearoom’s alcoves on special occasions.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

“Chestnuts” by Muqi. Part of “The Heart of Zen” exhibition at the Asian Art Museum.

Both scrolls present their titular subjects isolated on a paper ground, as if nothing more might be needed or wanted than the contemplation of a small grouping of fruits or nuts. Though recent scholarship has complicated this interpretation, it’s little wonder 20th-century U.S. and European scholars identified the two artworks as unparalleled exemplars of Zen painting, an idea that exponentially increased the fame the paintings had garnered over the centuries in Japan.

It’s clear the paintings warrant their reputation.

Six persimmons sit in undefined space. Each globular blob differs in its exact presence. In the center, the darkest one anchors the group, but the visual weight of its dark ink livens in its variation, as complex as a Rothko color field painting. Some fruits seem to sit behind others, but without any indication of a shelf, ground or branch, the setting is entirely in the mind of the viewer. The body of the leftmost fruit exists only in the faintest of washes, a line nearly interrupted by the dryness of the brush as it completed the circle, seemingly as exhausted as a marathon runner at the finish line.

“Persimmons” (“Six Persimmons”) by Muqi. Part of “The Heart of Zen” exhibition at the Asian Art Museum.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

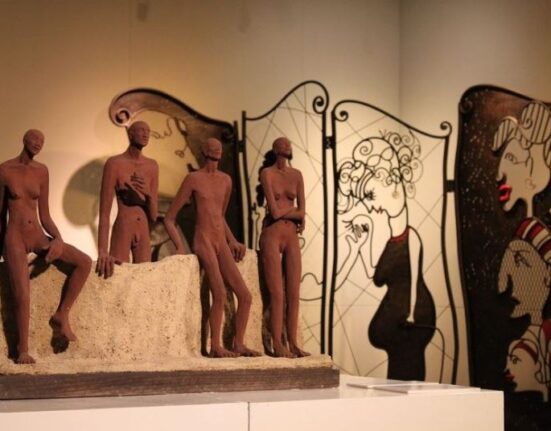

The spare design of the exhibition uses screens evoking Japanese temple architecture to divide the space. After several turns past a meditation area and a slide show of the Ryokoin Temple, the viewer is left directly in front of the artwork with no other distractions.

The ink’s fluidity registers the artist’s every pause and gesture. Alert stems and leaves topping each plump fruit can be read in sequential order like calligraphy strokes, placed just so by a steady hand. Viewing the residue of the painter’s movements, one may feel like they’re standing next to Muqi across the Pacific Ocean, across the centuries.

“The Heart of Zen,” exhibition installation 2023

Asian Art Museum“You have to look at it,” curator Laura Allen said, explaining that viewing the scrolls is much like Zen tea practice, which emphasizes mindful awareness of the moment.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Indeed, “Persimmons” and “Chestnuts” will demand your attention, unmediated by a commemorative selfie that would attest to your once-in-a-lifetime experience but distract you from being present.

In turn, Allen said, the paintings reward each viewer a lifetime of material for thought.

“It’s really enigmatic,” she said. “I first studied them in college, and I definitely spent time trying to figure out why they linger in your mind.”

The medieval paintings are now more famous than ever thanks to this show. First Lady Jill Biden and Second Gentleman of the United States Douglas Emhoff visited the exhibition the day before the exhibition opened for the public on Nov. 17, during the Asian-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

But can their contemplation — our ours — inside an orderly museum gallery or monastery elicit compassion for the kind of human suffering that exists outside those quiet spaces, as Abbot Kobori Geppo hoped in loaning the paintings?

Located between the Tenderloin and Civic Center BART station, the Asian Art Museum’s stately Beaux-Arts building makes for a stark juxtaposition with what Abbot Geppo must have seen on San Francisco streets in 2017. Sharing the paintings’ serenity for even a brief time felt like a privilege that ought to be shared with others, especially those whose lives grant little rest. Perhaps that is what the abbot envisioned.

Letha Chi’en is a freelance writer.

More Information

“The Heart of Zen”: Paintings. 1-8 p.m. Thursday; 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Friday-Monday. “Persimmons” will be on view through Dec. 10. “Chestnuts” will be on view Dec. 8-31. $14-$20. Asian Art Museum, 200 Larkin St.. 415-581-3500. asianart.org