The past decade has seen a rise in hysteria regarding digital art. As the scope of what constitutes new media creation continues to widen, it is tempting to be swept into the anxiety around world domination by advancing technologies such as AI – yet the future of this art genre remains inextricable from streams of fashion, technology and, most cloyingly, its saturation of Sino-Oriental aesthetics.

The cross-sections of technology, futurism and fashion recall many entities. Such include Donna Haraway’s cyborg bodies, projections of Hajime Sorayama in avant garde couture, the full spectrum of neo-noir grading in movie stills from Lost in Translation, amid other ephemera that loosely assign themselves – at least according to the Western imagination – under the East Asian wing of digital art.

Adjunct to this, we can consider US essayist Martin Heidegger’s claim in The Age of the World Picture: ‘The relationship between subject and the world is symbiotic in the sense that he has access over and over to the picture – yet it also is an extension of him.’ Here, Heidegger’s Age of refers to the modern or contemporary lens of understanding upon which this perspective can be accessible to the human subject, while still framing an inconclusive picture of the world. With this in mind, to demystify digital art would need to raise the questions that meet our own prejudice and complacency. How can we vault towards a future of digital art without the detritus of cliché? What can be introduced to pre-existing modes of techno-orientalism in digital art and how do we foster this introduction with requisite understanding of how to approach modes of East Asian art, by and for the community?

The visual economy of digital art has become a form of currency in itself. ArtsHub speaks to the curatorial board and digital artists of colour at Sugar Glider Digital (SGD) to gain an understanding of digital art and its overlaps with East Asian motifs and technology.

The contingency of self

As far as the eye can see, digital art suspends ideas of presentation and representation. Sugar Glider Digital’s Strategist and Curator, Michelle Wang, is certain this collision can foster a personal lens of viewing. ‘New media art is all about conversations between artistic forms, which results in unexpected and compelling artworks and often a unique lens on personal and political cultural experiences… I love how digital art breaks down the silos of creative practice to birth rich knowledge-sharing and opportunities for experimentation.’

If art is to hold any resonance online, it must reflect inwards on plurality. Graphic designer and 3D visual artist Sammy Yee’s chimeric expressions meld colour and petal-soft visuals in a gentle array. She is motivated by factors of the intangible – human psychology, interconnectedness, perceptions of energy and mass. Her work is a reflexive study, embracing the hybridity of her upbringing – one doctored by the presence of beauty and, simultaneously, violence.

‘Growing up with an Asian heritage in a Western upbringing has inevitably shaped the way I am and live in this world and this has trickled down to my creative process,’ says Yee. ‘It has taught me to question everything, to go back to understanding history, migration, cultures, acceptance and get to know where we are today.’

Yee’s landscapes present muted pastels and holo-chromatics, an artistic signature that may tell us about the protraction of her own learnings. Her artwork engages viewers through a slow, diffusive, yet distinctly light-handed lens. Chrome – long a relegated signifier in digital art – is moistened by the addition of nature in bloom, writhing and warping into frame. In animation, the fibres of emotion peek through her work.

If upbringing is indeed a pre-eminent through line for digital artists, Timothy Lee approaches this with caution. The artist and designer says, ‘I am still very conscious of anything I create that refers to an “Asian” experience. This can easily become a new authority that is then used to group us in the West.’ Under the moniker of Juune, he has produced a significant number of artworks for the Asian Australian umbrella of creatives. In his oeuvre, Lee’s projects engage with the idea of the past fomenting into the present.

Following a mixed reception to one of his pieces first exhibited in Sydney, Lee says, ‘The work I created recontextualised knock-offs in the way I appreciated them as a kid, and later, as an adult, it decentralises and redistributes the money that companies make from these billion-dollar IPs (Intellectual Property). I originally made the work because I thought it would be funny for that kind of artwork to be in corporate foyers in Australia, but it wasn’t received well because of the exact reasons I thought it was funny.’

The piece, titled Goofi (2023), reflects Lee’s artistic licence – largely collagist in method and intentional in piecing together the asymmetries of storied experience. Lee’s artwork cradles humour with contradictions and draws from the well of his own life. Moving to East Asia has freed him of any inhibitions to create art for a Western audience – imagined or reactive. It is no coincidence that Goofi has elicited a contrary response at West Bund Art and Design Fair in Shanghai, China with Sugar Glider Digital’s presentation, as compared to Sydney. Speaking on the exhibition of works – including by Lee and artists Si Yi Shen, Jonathan Puc, Craig SR and Nancy Liang – Wang says, ‘There’s a desire from the public to connect with Australian Chinese culture from new, decolonised perspectives, devoid of any objectifying gaze.’

In music, Lee cites Howie Lee, Gabber Modus Operandi and Jpegmafia as current streams of inspiration. His attitude is one that playfully deflects the need to be assertive – rerouting viewers to do the thinking. In this way, Lee is free to explore the overlap of his culture without limitation, tracing and retracing over what is thought to be known.

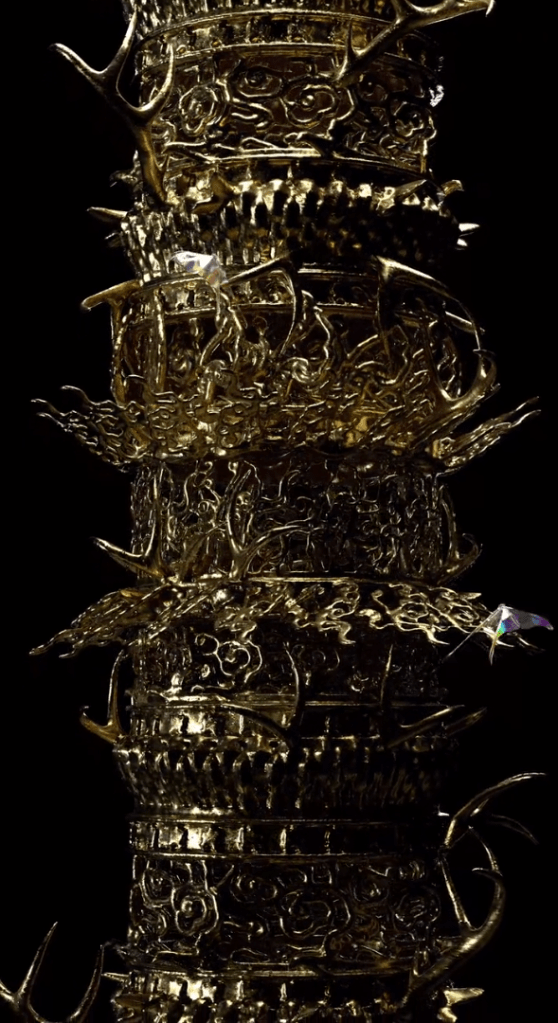

As its name suggests, Qilin Vessel, created by Craig SR, summons the iconography of ancient Chinese artworks through points of collision in the artist’s own identity and mythical gesturality. The artwork crosses thresholds of culture, world-building and othered consciousness, with an inspired locality, which viewers learn is honed over time. The artist says: ‘I really try to drill down my interest to something specific, or tie it to my interest in fictional worlds.’

The artefact, rendered in the same scaly detail of the mystical beast, Qilin, speaks to the creator’s own recalcitrance against the current atmosphere of digital art. ‘I think that’s what a lot of digital art lacks now – humanity. Technical 3D artists like myself probably get too excited by their craft and forget that generally people connect better to seeing human figures and semblances of people rather than abstract geometry.’

SR’s work is trans-historical, submerged in lore and the endless appeal of a non-exhaustive creative process. Inspiration hails from any corner of art, from US artist and film director Andrew Thomas Huang’s body of work to the auto-fiction genre. ‘It’s all just storytelling anyway,’ adds SR.

Notably, too, this rings true of the artist’s attention to the minutiae. Touch points in previous artworks have come from what he can find online or in real life, such as the patterns of a tiger’s pelt or the outline of lifestyle objects, candles and homeware. The hybridisation of old and new blends digital with reality; it imbues the vessel with the artist’s distinctive treatment of the hyper-surreal.

Wang tells ArtsHub: ‘The cross-pollination, in particular, of Asian and Anglo-Australian culture and artistic forms in digital art, not only enriches its aesthetic appeal, but reflects an incredibly vibrant and distinctive Australian artistic landscape made up of diaspora stories.’ More than a perfunctory token, Qilin Vessel enmeshes not only the past with present, but speaks to the artist’s ability to work at an opportune moment, drawing mythic from the mundane.

A future-facing apparatus

So, how do we move forward as digital art and technology continue to interweave? SGD’s proposition is to operate with a metric understanding of the phenomenon – actively navigating the nuances of subject and culture while upholding SGD’s core principles. Founding Director Emilya Colliver says, ‘While we think it’s essential to embrace the flexibility and accessibility of digital art, this is anchored by principles of art curation and placemaking. This means supporting emerging digital arts practitioners with paid opportunities and bringing their work to life in public spaces, where it can be engaged with by new audiences.’

Digital art reflects an ever-fluctuant taxonomy. A stance of radical receptiveness in allowing East Asian digital creatives to author their own stories is only the first step. There remains much to harvest in the sprawl.

Read: Live Futures: an inquiry of queer sex and play

We can only learn from the ongoing dissemination of digital art and its development if we can bind digital creation with profundity and personhood. Yee’s practice can be read as a testimony to this future, which in her words is characterised by ‘transitory energy, undulating fluidity – soft and bold’.

Repairing the division between object/subject and technology, digital art contributed by the Asian Australian diaspora embodies a reconciliation of opposites. For these artists, the future seems to be coming into focus.

This article is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.