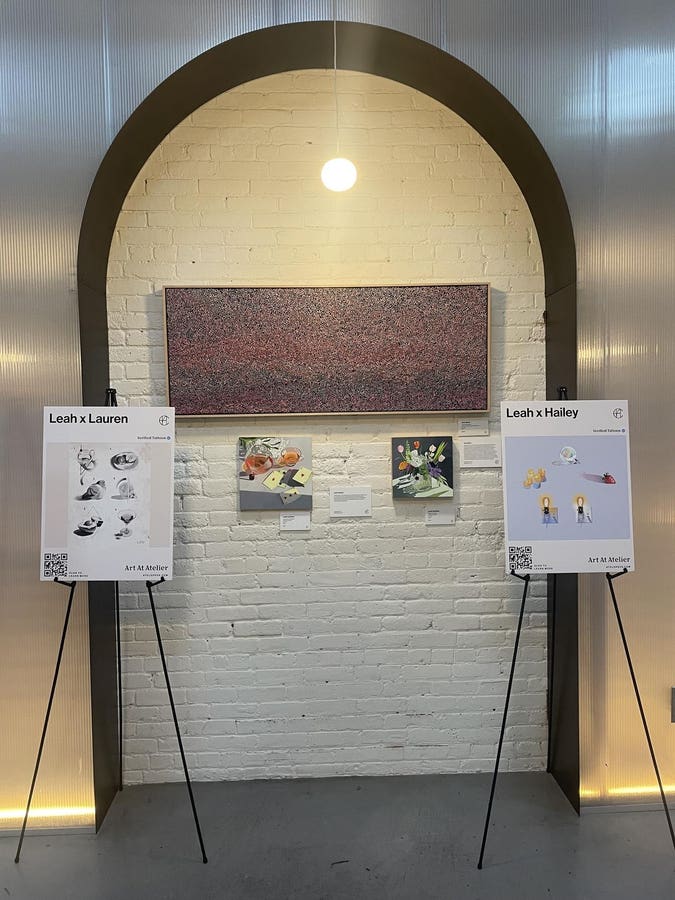

Installation view of Art at Atelier: Wear Your Art on Your Sleeve opening in Williamsburg, Brooklyn

Hailey self-identifies on Instagram as a florist and lepidopterist (a person who studies or collects moths and butterflies, as exemplified by the late Vladimir Nabokov), so it’s unsurprising that her artwork emphasizes floral imagery, fine lines, and ephemeral designs.

Viewing examples of her work for the first time last month, we encountered a ripe, bright red strawberry, with a natural shine, and fresh looking green caps. Its elongated, realistic shadow drew our gaze to the left, evoking centuries of symbolism. Strawberries adorned the marginal illuminations of medieval books of hours. Pointing downward, they represented drops of Christ’s blood, and the five petals of their white flower signified his five wounds. Shakespeare referenced the delicate, heart-shaped fruit embroidered on Desdemonda’s handkerchief in Othello, and again when the Duke of Gloucester beseeches Bishop Ely to “send for some” in Richard III. The Bard clearly borrowed from Raphael Holinshed’s sixteenth-century The Chronicles.

Lofty literary allusions aside, Hailey’s depiction of the widely-grown hybrid species of the genus Fragaria was a welcome personal reference for my husband Mike, son Michael, and me. Ahead of eying it at the Art at Atelier: Wear Your Art on Your Sleeve opening in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, alongside a painting by Chicago-based autodidact visual artist Leah Gardner, Michael and I had suggested that Mike get a strawberry tattoo in honor of our second Rescue dog Fresa (Spanish for strawberry), as he already had our first rescue pug mix Athena’s namesake emblazoned on his arm.

“A work of art which isn’t based on feeling isn’t art at all,” said Paul Cézanne.

Hailey found inspiration from Gardner’s work to break beyond her signature style, a creative collaboration that is celebrated with Atelier Eva’s second annual (and first on public view) Art at Atelier art exhibition. It’s a rare glimpse into how the two art forms inform and influence each other.

“Instead of conforming to a single vision, each tattoo artist is free to explore, express, and create,” according to Atelier Eva’s website. The airy tattoo studios are housed in an industrial-chic North Williamsburg boutique condominium, a stark contrast from neon signs that woo passers-by into cramped spaces where regrets are often made on a drunken whim.

Installation view of Art at Atelier: Wear Your Art on Your Sleeve opening in Williamsburg, Brooklyn

That creative freedom, underscored by the pairing of visual artists and tattoo artists, is essential in elevating the latter to a fine art form. Tattoo art continues to rise in status, building on the fungible space that blurs the boundaries of street art and studio art and gallery art and museum and auction art and fine art.

“With its traditional and potentially spiritual nature, tattooing easily qualifies as a folk art. However, given the skill and artistry of certain tattooists …, tattooing also is among the fine arts,” according to the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. “Whereas tattooing was once a hobby associated primarily with sailors, carnival workers, and prison inmates, tattooing today is featured in major museum exhibitions.”

Installation view of Art at Atelier: Wear Your Art on Your Sleeve opening in Williamsburg, Brooklyn

Atelier Eva is part of a burgeoning global trend.

Last year, the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam hosted a pop-up tattoo parlor, with tattoo artists replicating the Dutch master’s work on the flesh canvas of paying visitors. A year earlier, the New Museum partnered with Ace Hotel New York and Ace Hotel Brooklyn for an eight-part series that included tattoo sessions featuring special flash artworks. Auction houses such as Guernsey’s and Bray & Co. have broadened the collector market for tattoo art.

At least one artist has taken a less subtle approach. In February, a Swiss collector bought 12 pieces of tattooed skin of Austrian performance artist Wolfgang Flatz, including the artist’s name written in Cyrillic and a quote by the Roman philosopher Cicero: “Dum spiro spero” (while I breathe I hope). The controversial first-known sale of human tissue as art was originally planned as a charity auction led by Christie’s.

Installation view of Art at Atelier: Wear Your Art on Your Sleeve opening in Williamsburg, Brooklyn