Women artists continue to be significantly under-represented in taxpayer-funded galleries in Australia, a new national report has found.

The data, published today in the 2022 Countess Report, shows the proportion of women artists exhibiting across seven of nine gallery types declined between 2019 and 2022.

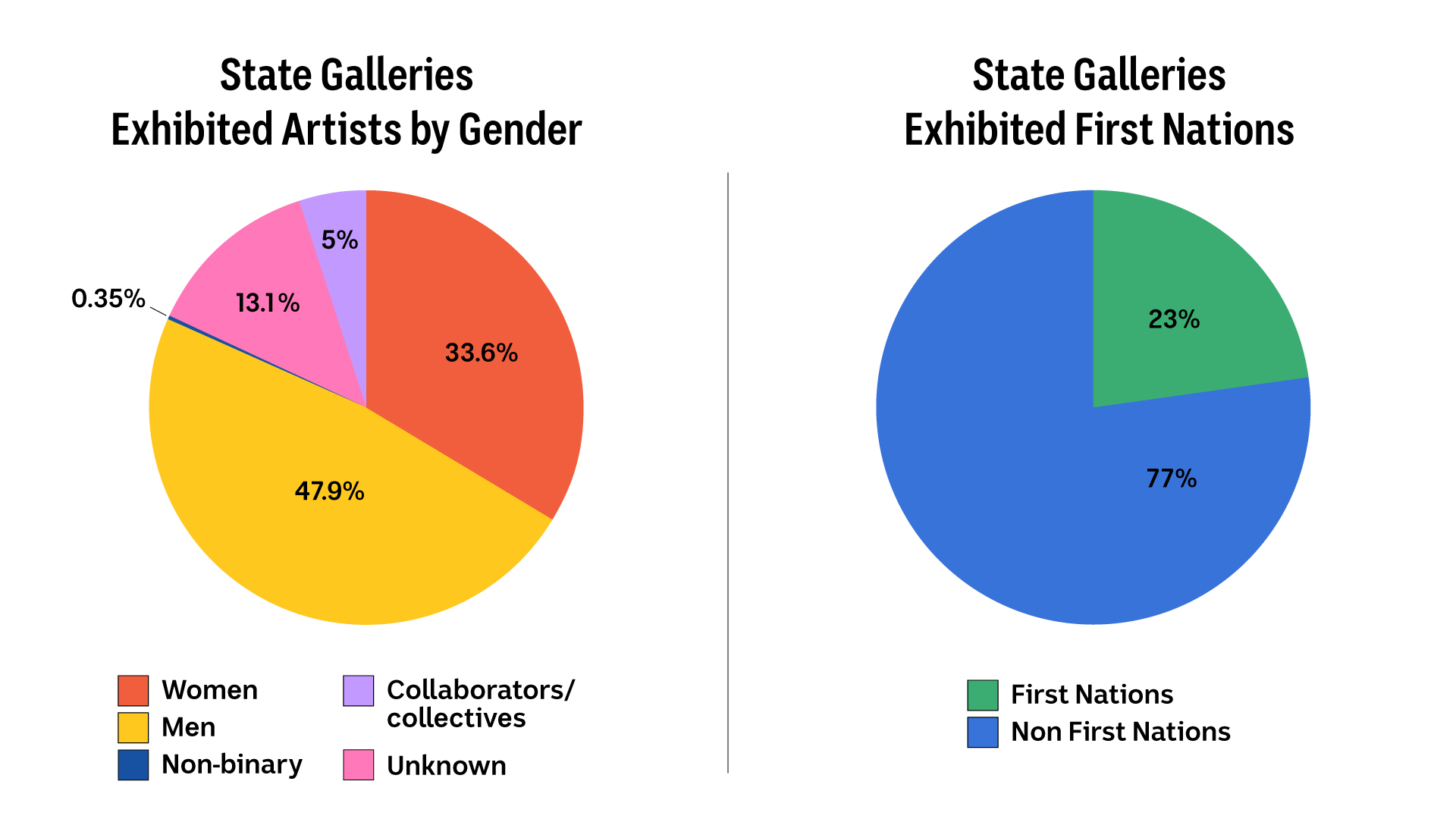

Among public-funded state galleries, women accounted for 33.6 per cent of exhibiting artists, while in major museums, they made up just 30.5 per cent.

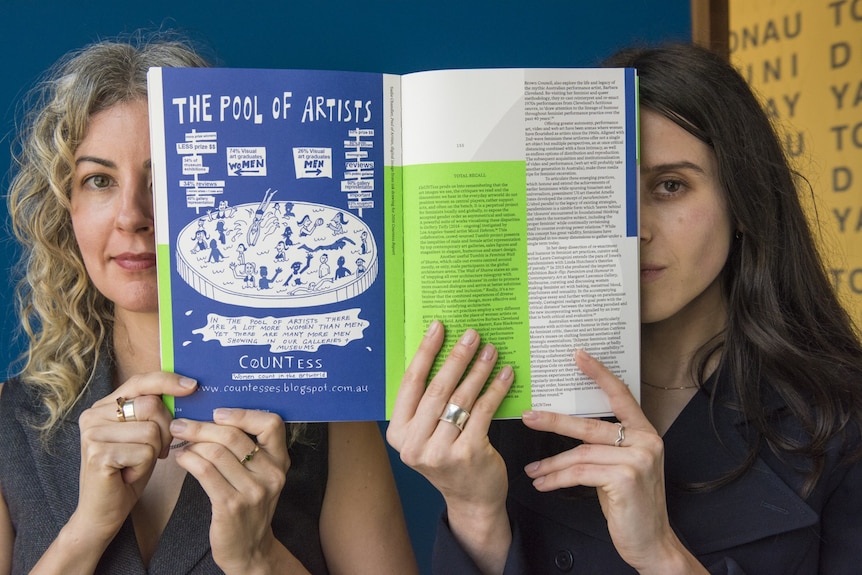

The Countess Report, published every four years, is an independent and artist-run data collection initiative that tracks gender representation in Australia’s visual arts sector.

The project was first set up by Melbourne-based artist Elvis Richardson in 2008, via her blog Countess, to redress the lack of publicly available data on gender representation in major galleries.

It has since grown to a team of four researchers, with backing from the National Association of Visual Artists (NAVA), Creative Australia and the Sheila Foundation.

The report released today is the third major sector-wide survey and includes data on more than 21,000 artists and arts workers from more than 450 galleries.

Co-editors of the report Miranda Samuels and Shevaun Wright found that gender representation across the gallery sector had stagnated or declined since the previous Countess Report was published based on data from 2018, which showed representation of women artists in state galleries at 34 per cent.

That figure has dropped from 37 per cent in 2014.

Wright, who is a First Nations artist and lawyer, says the findings represent a “business-as-usual” attitude from the sector.

“Unfortunately, it’s reflecting a ‘going back to what you know’ [attitude], rather than really taking the risks of shifting culture,” she says.

“But I think it’s an opportune time to really reflect on why we continue returning to these traditional strongholds of the male artist.”

The latest findings come despite pledges made by major galleries to address gender inequity in the wake of the 2018 report.

“I was surprised that there had been a slide backwards [in representation] given the attention and conversations that were started around the importance of gender representation [after the last report] and the fact that women still continue to outnumber men as art school graduates,” says Samuels.

Gender equity stagnates

The report shows men also outnumbered women in acquisitions by state galleries in 2022 and earned a greater share of prize money.

Although women artists accounted for more than half of the winners of major art prizes (53 per cent) and, in 2022, won four out of the six richest prizes, men received a higher average amount as their winnings. (Women prize winners earned an average of $44,947 while men earned $51,818.)

Samuels says it’s important to consider broader structural inequities faced by women when interpreting the findings.

“We live in a society that’s ruled by ideas of value that are informed by capitalist structures, and under that, women’s work generally is less valued or undervalued compared with men’s work,” she says.

“In the art world, you can see it in terms of artwork pricing and values; you see it in the secondary market, where women’s work sells in significantly lower numbers; and you also see that there is a significant wage gap that exists between women and men artists.”

Of the 1,963 acquisitions made by state galleries, works by women made up just 32 per cent. Men accounted for 53 per cent, while artists who identified as non-binary or “other” accounted for 15 per cent.

The economic disparities outlined in the report echo the findings of the most recent national artist income survey, showing that total income for women artists is 25 per cent less on average than men — greater than the national gender pay gap.

While state galleries and major museums continue to lag on gender representation, other parts of the visual arts sector fared better in the report. Commercial galleries, university art museums, contemporary art organisations, public galleries and Aboriginal-owned arts centres outperformed state galleries and major museums, reaching or surpassing gender parity.

First Nations-owned arts centres had the highest representation of women artists, at 75.9 per cent.

Major museums ranked lowest for representation, at 30.5 per cent.

Except for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, none of the major museums reached gender parity. The lowest figures came from the privately owned Museum of Old and New Art, Hobart (17 per cent women artists), and White Rabbit Gallery, Sydney (15 per cent).

First Nations artists counted

The latest Countess Report also includes data on First Nations representation in the Australian art sector for the first time.

“[First Nations art] holds a great cultural importance to us, but in terms of looking at how it actually operates on the ground and the respect that is shown to First Nations artists as cultural producers, I think [the findings] are eye-opening and really the beginning of a conversation,” says Wright.

The researchers found that First Nations artists account for fewer solo shows and acquisitions by state galleries and have lower levels of commercial gallery representation compared with non-First Nations artists.

The report notes that First Nations artists are more often included in group exhibitions rather than solo shows.

“With First Nations artists in particular, [there] is a tendency towards sequestering [their work] and separating it out thematically in exhibitions,” says Wright.

“So I would like to see more thinking about it [First Nations art] being embedded in the whole of art programming … not thinking of them as an add-on, but as something that is foundational to our national culture.”

The data shows that among First Nations artists, gender inequity prevails with men outnumbering women artists in state gallery exhibitions and acquisitions.

The researchers also analysed organisational structures in the gallery sector and found First Nations artists to be poorly represented in governance roles and on gallery boards.

The executive director of NAVA, Penelope Benton, has described the findings as “sobering” and called for “immediate action from both the galleries and governments”.

“These findings demonstrate the urgent need for targeted interventions to address the intersectional challenges faced by First Nations women artists, exacerbated by the absence of First Nations representation among boards and staff across the sector,” says Benton.

“Policy change and investment is urgently needed to address the glaring gap in career pathways for First Nations arts workers and leadership roles within the visual arts.”

Policy intervention needed

The report includes a breakdown of gender representation by gallery — more than 450 in total.

Individual galleries performed better than others, with Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA) and the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) all boasting a higher proportion of acquisitions for women artists.

The NGA was the top-performing major gallery with the highest proportion (84.4 per cent) of women artists represented in exhibitions. That figure has ballooned from 25 per cent in 2018.

Both the NGA and AGNSW introduced gender equity programs after the release of the 2018 Countess Report.

“From the reporting that we’ve done over the past four years, it would seem like those initiatives have been contributing factors to their numbers,” says Samuels.

The NGA’s five-year gender equity action plan and associated Know My Name initiative marked the first time a major publicly funded gallery had committed to a 50-50 gender representation target.

Benton agrees the approach has merit but says sector-wide reform is needed.

“The latest Countess Report highlights the urgency of implementing long-overdue reforms. The slow progress in addressing gender equity in the visual arts emphasises the need for proactive measures to dismantle systemic barriers and promote diversity and inclusivity,” says Benton.

“NAVA asserts the critical importance of governmental and institutional policy change to effectively address these disparities. Without meaningful reforms at all levels, progress towards gender equity in the visual arts will continue to lag.”

Posted , updated