Faith Ringgold, a larger-than-life visual artist, quilter, storyteller, and activist, has passed away at age 93. Her death was confirmed by her family and ACA Galleries, which has represented her since 1995. She died in her home in Englewood, New Jersey, on Saturday, April 13.

Ringgold was a beloved Black American artist, most famous for visually stunning “story quilts” tackling race, gender, and social justice struggles in the United States. With a career spanning seven decades, over 80 awards and honors, 20 children’s books, and major museum shows worldwide, she left a massive imprint on American art.

Born Faith Willi Jones in October 1930 in Harlem, New York, she grew up around Harlem Renaissance artists, musicians, and intellectuals, among them W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, Amiri Baraka, and Sonny Rollins. In 1959, she completed her Master’s degree in art from the City College of New York, and embarked on a cross-Europe trip with her mother and two daughters, visiting Paris, Florence, and Rome. In 1967, she made one of her major early works, “American People Series #20: Die,” now on view at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Channeling Pablo Picasso’s 1937 “Guernica,” the 12-foot mural addresses America’s race relations in the 1960s: a chaotic scene of warring Black and White Americans, bleeding from knife and gun wounds.

“I couldn’t paint landscapes in the 1960s — there was too much going on,” she explained in a 2018 interview with Hyperallergic. “This is what inspired the American People Series. For me it is important to make work about peril if it’s your story. One can find beauty in horror that you can share through your art and ideally effect change.”

She continued: “It’s important to me to express the ills of society that are widely accepted while also delivering the message without only seeing the ill. I try to show both the good and the ill. For example, Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ — all the bad and evil was depicted in such a way that you can deal with it. For me that is key.”

Another influential work was “Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima?” (1983), her first story quilt. Made of 56 square panels combining paintings and text, the quilt tells the fictional tale of Jemima Blakey, an independent Black woman from New Orleans embodying a total contrast to the artwork’s eponymous racially stereotyped figure. Jemima’s character and others in the story are based on women in Ringgold’s family. The quilt was first displayed at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1984.

“I paint from my experience. This is what I know,” Ringgold told Hyperallergic in the aforementioned interview. “I am not a man or European and wanted to learn and express the lives of my sex and people — not others. So it is important to me to include my people in the conversation. These political and feminist works are more relevant today than ever — it’s important to keep the women’s movement and the social justice issues alive — keep it going.”

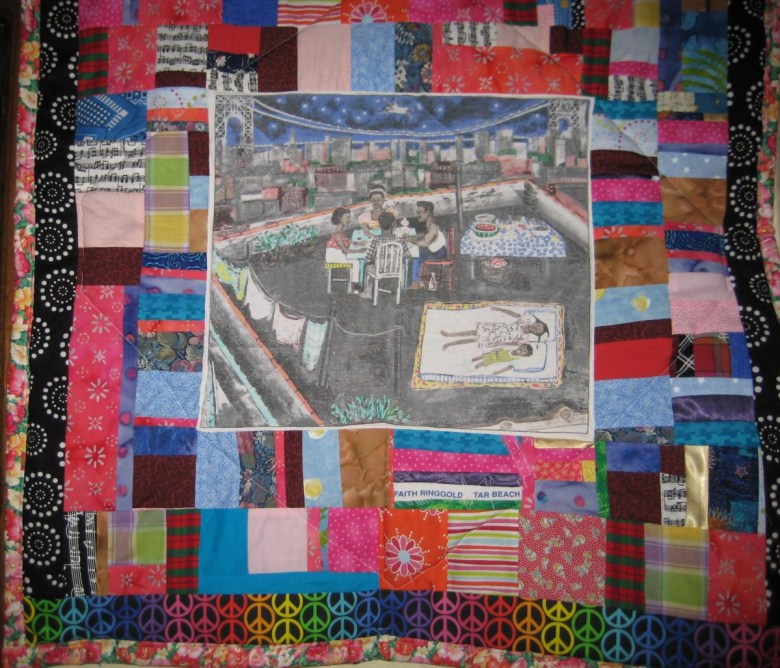

In 1988, she made “Tar Beach,” the first of five quilts in her popular Women on a Bridge series. The story’s child protagonist and narrator Cassie Louise Lightfoot flies over the George Washington Bridge on a Harlem summer night. “Only eight years old and in the third grade and I can fly. That means I am free to go wherever I want to for the rest of my life,” Cassie says in the work, which Ringgold adapted into a namesake children’s book published in 1991.

Throughout the decades, Ringgold continued experimenting with painting, fabric, sculpture, mask- and doll-making, and performance art. Her work was exhibited everywhere from the White House to Rikers Island prison. As an organizer, she co-led a group of Black members within the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC). The group pushed New York’s museums, among them MoMA, the Guggenheim, and the Whitney, to lower admission costs and increase representation of artists of color. The group is credited with persuading MoMA and several other museums in the city to institute a free-admission day.

“No other creative field is as closed to those who are not white and male as is the visual arts,” she once said. “After I decided to be an artist, the first thing that I had to believe was that I, a Black woman, could penetrate the art scene, and that, further, I could do so without sacrificing one iota of my Blackness or my femaleness or my humanity.” She achieved that and much more.