The Herb Alpert Foundation has announced the winners of its 30th annual Herb Alpert Award in the Arts, which recognizes mid-career artists in the fields of dance, music, film/video, theater and visual arts.

In all, there are 10 winners for 2024, each of whom will receive a $75,000 unrestricted prize as well as a residency at CalArts (which administers the prize on behalf of the Herb Alpert Foundation). The winners are chosen by a group of 15 distinguished panelists and are nominated by another group of respected names in the arts.

According to Irene Borger, the director of the Herb Alpert Awards in the Arts, what stands out among 2024’s cohort is how many winners work across genres and mediums.

“Over the years things have gotten more and more hybrid, so that even though there are these five categories, these five genres, one of the choreographers is coming out with a book, one of the filmmakers makes sculpture, one of the visual artists makes sound spaces,” says Borger. “It’s like they are all multi-hyphenates. The boundaries have melted away. People are working in very different spaces.”

In dance, the winners of the Herb Alpert Award in the Arts are Jonathan González and Mariana Valencia; for film/video, Nuotama Bodomo and Lucy Raven; in music, Huang Ruo and Anna Webber; for theater, Robin Frohardt and Cannupa Hanska Luger; and in visual arts, Marina Rosenfeld and Marie Watt. Eligible artists must be living and working in the United States.

Legendary musician, philanthropist and artist Herb Alpert and singer Lani Hall, his wife, created the Herb Alpert Foundation in 1985. Over the course of nearly four decades, the foundation has awarded more than $200 million in grants and donations and presented the Herb Alpert Award in the Arts (HAAIA) to 174 artists. Past HAAIA winners include visual artists Carrie Mae Weems, Kerry James Marshall, Cai Guo-Qiang and Sharon Lockhart, theater artist Taylor Mac and playwright and showrunner Suzan-Lori Parks.

Clockwise from left: Lani Hall Alpert, Herb Alpert, CalArts president Ravi Rajan, Herb Alpert Foundation president Rona Sebastian and Herb Alpert Award in the Arts founding director Irene Borger.

Shawn Connell Studio

Last year, Alpert told The Hollywood Reporter that what motivates his giving is that, “I believe in the arts. I think the arts are the heart and soul of our country. Not just music. We’re talking about actors and poets and painters and sculptors — the whole gamut. We need the artists, especially in these times.”

The panelists for the 2024 awards include: Bill T. Jones director and curator of performing arts at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, Stanford Makishi, vice president and artistic director, dance, New York City Center, and Charmaine Warren, founder/artistic director, Black Dance Stories and producer of DanceAfrica@BAM (dance); Pablo de Ocampo, director and curator of moving image, Walker Art Center, artist and filmmaker Arthur Jafa and artist Leslie Thornton (film/video); musician and composer Steve Coleman, composer Adam Fong and composer Julia Wolfe (music); Natalie Garrett, co-artistic director One Nation/One Project, Maria Goyanes, artistic director, Woolly Mammoth Theater, Meiyin Wang, director of producing and programming, Perelman Performing Arts Center (theater); and curator and writer Ruth Estévez, artist Emily Jacir, artist Tanya Lukin Linklater (visual arts).

“The panels change every year,” notes Borger, “so you never get the same panel, though sometimes we invite people back or invite people who previously won the award, such as Arthur Jafa who sat on the panel this year as did Leslie Thornton, who won the very first award in film/video. She has a show right now at the Museum of Modern Art. One of the things about the Alpert Awrd is that you can see it over time — it has its finger on the pulse of culture. At least 20 winners have gone on to get MacArthurs or they go on to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. But they got the Alpert Award first.”

While the Herb Alpert Award in the Arts publicly releases the names of the panelists who choose the winners, the separate group of nominators remain anonymous and artists who are nominated are then invited to apply for the honors.

“Every year, there are 50 nominators, ten in each of these five fields,” explains Borger, “and each nominator nominates two people. They will give us the names and contact information of two people they think are really superb and then we invite them to apply and then they submit work samples and it’s then that the three-person panels choose the recipients.”

This year’s winners of the 30th Annual Herb Alpert Award in the Arts honors will be recognized and honored during a virtual event on Thursday, May 2, at 2 p.m. PT. Read on for more about the winners below, based on their artist bios:

The 10 Herb Alpert Award in the Arts Winners for 2023

Dance

Choreographer Jonathan González, who trained as a musician in opera, French horn and piano, creates works that sit at the intersection of performance and theater and both gallery and site-specific settings. He also creates video art and dance for film and writes poetry, prose and criticism. A member of the faculty of the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation González, who lives in Philadelphia, is currently working on a project at the American Academy of Arts and Letters in Harlem as well as on his first book Ways to Move: Black Insurgent Grammars, due in 2025. “We let ourselves arrive somewhere unknown and listen to how it meets a public. In the act of making and sharing performance, there is the opportunity for casts and audiences alike to experience moments of the sublime, of beauty, of ideological instability, within the precious container of gathering to experience. That is undeniable,” he says in a statement.

Choreographer and dancer Mariana Valencia describes her performances as autobiographical and lyrical, made from rigorously ordered sequences where movement, song and spoken text are often improvised in front of audiences. She works mostly in solos and duets, and in collaboration with musician Jazzy Romero. Her pieces foreground personal experiences against broader cultural contexts, for example, “conjuring a childhood memory of doing domestic work with my grandmother,” she shares, “or referencing Barack Obama’s singing of ‘Amazing Grace’ after the 2015 mass shooting in Charleston.” Her movement vocabulary draws between vernacular (for example, cumbia and pedestrian) and modern dance forms (Martha Graham, Lester Horton). Valencia, who lives in Brooklyn, is currently beginning to look back at her archive of older work, setting it on the bodies of younger dancers. “My performances are set as if we’re feasting together,” she says. “I place the food on the table, we eat with our hands, perhaps we taste something new. We feed ourselves and each other from the bounty, we make eye contact, and we pass along the flavors of the fare that lies within our reach.”

Film/Video

Filmmaker Nuotama Bodomo says she became a filmmaker because of her migrant childhood; she grew up in Ghana, Norway, Hong Kong and the United States. After early successes in cinema production, she started to explore film from a perspective of Afro-indigenous visuality and relishing moving images as a “mother tongue” that is silent and/or unspoken. Bodomo, who lives in Queens, New York, is currently in post-production on a docu-hybrid, Afrofuturist contemporary retelling of the legend of Yennenga. a forgotten warrior princess from 12th century Ghana. “I came to film because I needed to express from an authentic, untranslated place,” she says. “I intend to use that jumping off point to make radical changes to this medium so that it can become accessible in ways that will truly speak to its potency and its power.”

Filmmaker and artist Lucy Raven’s multidisciplinary practice includes still photography, installation, sound, and performative lecture — all in the service of investigating the hidden ideologies, histories, and labor forces behind global image-making industries as she describes it. For the last six years, Raven, who lives in New York, has been working on a film trilogy on the American West. She is presently at work on the third installment in the trilogy, which centers around the removal of four large dams on the Klamath River in Northern California. The removal follows 20-plus years of grassroots activism by five tribes along the Klamath, who protested the dams for cutting off 400 miles of cold-water habitat for the spring season Chinook, one of the largest Chinook runs in the country while generating a tiny amount of power relative to its grid. “I trained as a sculptor, and while I focus primarily on making moving image works and installations, I think of how images are connected through time, and presented in space, as a fundamentally sculptural concern,” she says.

Music

A composer of symphonic and chamber music and opera, Huang Ruo is a first-generation immigrant who sees himself “pursuing the American dream.” As part of a project to create work inspired by Asian culture and Asian American stories to be programmed and performed in the classical music world, he has composed nine operas in the last 10 years. Some of his recent works include an operatic version of the Tony Award-winning play M. Butterfly; The Book of Mountains and Seas, drawn from a classic compilation of Chinese mythology first transcribed in 4th century B.C.; and Angel Island, inspired by Chinese poems carved on the walls of the Angel Island immigration station in the San Francisco Bay, where immigrants were sometimes held for years in brutal conditions. His next opera, An American Soldier — based on the true story of Chinese-American army private Danny Chen who was found dead in a guard tower at his base in Afghanistan and on the ensuing court-martials of Chen’s fellow soldiers — is having its New York Premiere at Perelman Performing Arts Center (PAC NYC) in May. The libretto is by well-known author David Henry Hwang. A composition professor at the Mannes School of Music, Huang Ruo lives in the Bronx. “I have written nine operas; each one of them with Asian subjects, or Asian-American subjects,” he says. “There are so much timely and important Asian and Asian-American stories to be written and told; who tells them is important.”

Composer/performer, Anna Webber, a saxophonist and flutist, situates herself in the jazz world. In a primarily band-based practice, Weber, who lives in Greenfield, Massachusetts, has cultivated long term musical relationships with groups of musicians and written music specifically for their instrumental voices and personalities. Her goal, she says, is to create frameworks in which the performers are free to be themselves within a multitude of situations, and while she doesn’t think of her music as inherently political, she enjoys subverting the myth of the solitary “genius” composer. A recent focus is translating her improvisational vocabulary into a codified, notated language, resulting in using timbre and sound as organizing forces that are as important to her as harmony. Her interests in timbre and sound have led her to research acoustics and psychoacoustics and how they intersect with human perception. “I believe that there should be a continuum between my compositional and improvisational vocabulary, so I set out to bring those languages closer together,” she says.

Theater

Theater maker Robin Frohardt creates intricate puppetry-based performances, through sculpting, painting, writing and performing. Attracted to puppetry’s traditional exemption from seriousness and the humbleness of its materials, her narratives consider capitalism, consumerism, and the resulting environmental catastrophe through a darkly humorous lens. Her work integrates shadow puppets, animation, bunraku and music. Frohardt, who lives in Saugerties, New York, is presently at MassMOCA working on installing the latest iteration of The Plastic Bag Store, an immersive puppet theater work with a transforming set that the audience travels through; it includes a mock grocery store filled with products crafted entirely from discarded plastic. She is also developing Home Depot Parking Lot, combining cinematic and theatrical elements as a meditation on the relation between built and natural worlds. She says her dream is to present this work in shopping center parking lots around the country. “Rather than creating straightforward plays, I spend years meticulously hand-making fully realized worlds and characters into intricate puppetry-based performances,” she says.

Raised on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota, interdisciplinary artist Cannupa Hanska Luger works in sculpture and installation and indigenous futurism. His practice is rooted in the traditions of generations before him, learning clay work from Indigenous elders, welding from his parents, and sewing from his aunts. Hanska Luger interweaves performance and political action, provoking diverse audiences to engage with Indigenous peoples and values apart from mainstream America. As he describes it, “at times the work presents a call to action to protect land from capitalist exploits; at other times it brings people together for a shared experience of future-dreaming.” When working on sacred sites without viewers, he video-documents his performance which he views as both protecting the ceremony and the land while broadly transmitting his ideas to widening circles of audience. Hanska Luger, who lives in Glorieta, New Mexico, is currently creating performative work for Pacific Standard Time at the Hammer Museum, and for the Indigenous Futures exhibition at the Autry Museum of the American West. “I aim to create beautiful art but moreover, I want to lay groundwork, establish connections, mobilize action. I want to make real impact and this motivation increasingly pulls me out of the studio and into the world,” he says.

Visual Arts

Sound artist Marina Rosenfeld’s work is interdisciplinary. She creates performances and improvisations, installations, electronic media, experimental forms of musical notation as well as prints, sculpture, and photographs. In her lengthy history as a performer of improvised music, especially using turntables and dub plates, she has collaborated with choreographers and other musicians in a wide variety of contexts, from club to stage. Last fall she mounted a 48-hour performance in Sion, Switzerland, with an audience that slept, woke, ate, and listened together over a long cold night. Living in Brooklyn, New York and teaching at Brooklyn College, in addition to re-mounting some of her classic pieces, she is presently continuing to explore making works on paper. In September, inviting local performers to take part for the first time, she will direct a new staging of her work Teenage Lontano in Luxembourg. “My main interest is the invention and testing of new forms: I am only satisfied with an idea if it pushes at the limits of known forms, engenders a new strategy for posing a question, and engages with the tangled histories of its own making,” she says.

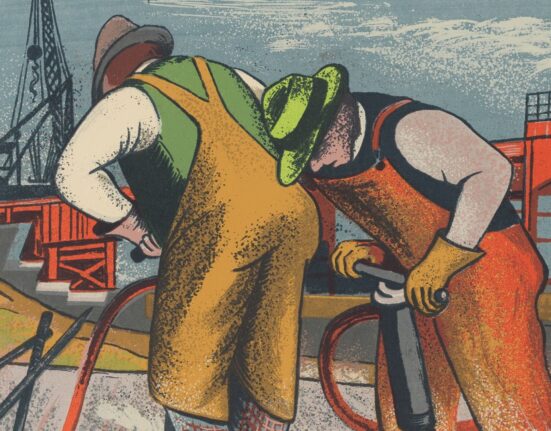

A member of the Seneca Nation, artist Marie Watt’s work draws on images and ideas from Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) proto-feminism and Indigenous teachings. Her interdisciplinary practice incorporates printmaking, painting, textiles, and sculpture. Some of her projects are solo in nature, while others are collaborative. In all of them, Watt, who lives in Portland, Oregon, explores how history, community, and storytelling intersect. A significant part of her practice involves setting a table for people from different backgrounds to come together and connect. This can take the form of sewing circles, community-built sculptures, or crowd-sourced participation in a project via social media. Throughout all her work, she says that the question she returns to is: “What would the world look like if we thought of ourselves as companion species?” Her most recent work is Skywalkers, a “steel quilt” installation at the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, which opened in April. “I am an artist, but I also consider myself a custodian of stories. I believe I have the responsibility to amplify the stories of others, set right historical blind spots, and speak up for those who can’t speak up for themselves: humans, animals, the natural world,” she says.