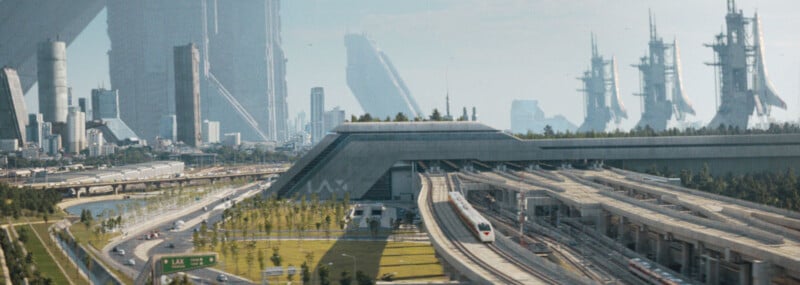

The Creator is a new science fiction film from Gareth Edwards (Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, Godzilla) that focuses on a future war where humanity is fighting against artificial intelligence.

Artificial Intelligence Is Everywhere

As burgeoning AI-powered technologies find their way into nearly every facet of modern life, AI is on everyone’s mind. While AI is generally useful, people are concerned about how AI technology reduces the human touch in art. More pressing are the concerns that AI may ultimately displace people across nearly every industry.

The Creator plays on this fear with its story, set in 2055, where an AI created by the U.S. government detonates a nuclear warhead over California. In the nuclear fallout, the U.S. and its allies pledge to remove AI from the Earth to save what remains of humanity. However, the AI fights back.

While there is no need to spoil much of the story, the basic idea is that a military agent, Joshua Taylor, played by John David Washington, is tasked with hunting down and killing the Creator, the mysterious figure behind the advanced AI that is rumored to have created a weapon that will destroy what remains of humanity.

The “weapon,” shown in the trailer above, is actually a young robotic AI child named “Alphie” whom Taylor elects not to assassinate despite his orders. What is spectacular about Alphie is that she demonstrates spectacular stellar — and challenging — visual effects, blending a human child, actor Madeleine Yuna Voyles, with robotic parts, including a cut-out that sees entirely through Voyles’ skull. The Creator is a tour de force in photorealistic special effects.

‘The Creator’s’ Visual Effects Supervisor, Jay Cooper, Talks Shop

Due to the prevalence of AI in the photography and video industry and the fascinating nature of how artists create photorealistic special effects, PetaPixel spoke with The Creator’s visual effects supervisor, Jay Cooper, who has worked at the famous VFX company, Industrial Light and Magic, since 1998.

Cooper worked on a considerable number of major films, including Babylon, Avengers: Endgame, Star Wars: Episode VIII — The Last Jedi, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, and so many more His list of credits is extensive, including work on nearly 60 projects.

Like Photography, Great VFX Starts with a Strong Understanding of Light

Photography plays a vital role in successful digital art and special effects work. While it may be easy to imagine that the powerful technology and bombastic film projects mean that visual effects artists are untethered by reality, the truth is that their work is grounded, no matter where a movie’s story takes them, by realism and how light interacts with the world. Few people understand light better than photographers.

AI in VFX Workflow is Still Budding

There is something interesting about using AI to help make a movie that shows some of the potential dangers of AI, but that is precisely what Cooper and his team have done. Some machine learning tools in Cooper’s workflow include upscaling tools that are not so different from what photographers use in software like Topaz Gigapixel AI.

Cooper and other visual effects artists use a version of AI upscaling that was developed in-house. They also have tools that help with understanding poses.

Not Moving Toward Generative AI

“But there’s nothing in our pipeline that we’re doing yet — or probably anticipate doing — that’s image creation. We feel like that’s best left to the place of our artists, who are able to understand what the client is looking for and make changes appropriately. That’s something that AI tools aren’t really great at, even as they are amazing at doing other interesting stuff. In terms of serving a client and going after a particular aesthetic, it’s sort of a wild west,” Cooper tells PetaPixel.

Cooper also hit on general advancements in software. Even as applications get exponentially more powerful, and the things that visual artists (or digital photographers) can do drastically change, the fundamentals stay the same.

Artists Need Good Fundamentals

“I don’t think it’s dissimilar from photography. If you started learning on a Pentax K-1000, which is the camera I learned at, fully manual, and then graduate to maybe a Canon 5D or something, there are all these new bells and whistles,” Cooper explains, “But your talent as a photographer, or an artist, that’s what you take with you. If you can find a composition, and you understand exposure, depth of field, those sorts of things, you’re a stronger photographer. Not because of the equipment you use.”

Some Talented VFX Artists Are Photographers

“That’s the parallel I see in visual effects as well. Our strongest artists are the ones that understand how light works, how composition works,” Cooper says, explaining that a photographic background offers vast benefits for digital artists trying to create photorealistic special effects, such as those seen in The Creator.

“The tools that you bring to bear are really your aesthetic eye more than anything,” Cooper asserts. “And then your ability to sort of manipulate the software to get the desired results.”

Budding visual effects artists often ask Cooper what software they should learn — similar to asking a professional photographer what photo editing software someone should know. However, Cooper says it is not about the specific software but what concepts a person should study.

“There are a lot of different ways to approach this industry. You can be a classically trained artist, you can be an art history major, you can be a photographer, you can be a videographer. All those things are essential. At ILM, we say, ‘Developing your eye,’ and those are essential. Those are essential if you’re doing effects simulation or composition or lighting, those are all really important. Looking at the way that light interacts in the real world…you’re trying to tease out the photorealistic cues that make your shots feel correct. That’s the one thing I’ve hoped to develop over my 25 years,” Cooper says.

Realistic VFX Require a Strong ‘In Camera’ Starting Point

In a similar spirit, Cooper cannot say enough good things about director Gareth Edwards and the directors of photography, Greig Fraser and Oren Soffer. Fraser could not be on set due to work on Dune: Part Two, but worked extensively with Edwards during pre-production. The actual filming process was done alongside up-and-comer Soffer.

While the visual effects work is integral to bringing everything together, especially in a sci-fi film like The Creator, a very strong photographic image is at the core of the final presentation.

Sony FX3 Shines in Major Motion Picture

Edwards and Soffer shot the movie on a Sony FX3 camera, an intriguing choice for a film with an $80 million budget. After all, at $3,900, the FX3 is one of Sony’s most affordable cine cameras.

It is an extremely bold and unusual choice, but given the results, it was clearly a good one. Edwards and Soffer opted for the full-frame SLR-style FX3 because of its compact, lightweight design and relatively strong performance in low-light conditions, where some huge, heavy, and costly cinema cameras can struggle. It shows that, much like with still photography equipment, talent reigns supreme over gear. Not that the FX3 is a bad camera, of course, it is just an atypical choice for a big-budget feature film.

“In terms of our ability to figure out how to make this thing look amazing and real, a lot goes into starting with a fantastic photographic image and sort of leaning into what was shot on set and elevating that world in a way that feels like a photo-real future environment,” Cooper says.

“You can take your images into Photoshop and dodge or burn your way to victory. We don’t really do that in the visual effects world. We don’t do a lot of plate manipulation,” Cooper explains, emphasizing that the work of photorealistic visual effects is to build upon what is there.

The same is true for color grading, which is an artistic choice that anything added or changed in a scene during post-production visual effects work must accurately reflect from start to finish.

In the pursuit of realism, working from a place of mixing real-world shots with digitally created elements can prove much more natural-looking than entire scenes shot against a blue screen.

In a cinematic landscape where it seems like nearly everything is shot in a big studio with fancy effects rather than on location, Edwards’ approach to The Creator, which was filmed in more than 80 locations throughout the world, is a breath of fresh air. And this commitment to achieving as much in-camera as possible pays huge dividends with the final product.

‘The Creator’ Is a Masterclass in Visual Language

As Cooper observes, it is tough to tell what is real and what is fake throughout the movie. Of course, some things are obviously artificial, like the missing parts of Alphie’s skull, but the overall presentation is so immersive that even what the viewer knows is not real can seem perfectly life-like. This is a challenging feat because seeing even a single crack in the façade when watching a film can entirely and irreparably break someone’s immersion.

“There’s such an authenticity to the backbone of this movie,” Cooper says, putting one of the The Creator’s biggest strengths into words.

The Creator is in theaters now and is produced by Regency Enterprises, eOne, New Regency, and Bad Dreams. The film is distributed by 20th Century Studios.

Image credits: All images and captions © 2023 20th Century Studios