LEXINGTON, Ky.— Currently at the University of Kentucky Art Museum, Disguise the Limit: John Yau’s Collaborations offers a survey of the poet’s collaborations with more than 40 artists over the last three decades. The exhibition highlights the many different ways Yau has worked with a wide range of visual artists over the past five decades. “The result of friendships and shared sensibilities,” writes exhibition curator Stuart Horodner, “Yau’s collaborations reveal his embrace of both representation and abstraction as foils for language generation.” Recently, Yau and I spoke about the origins of his collaborations and the show, his approaches to poetry and art, and other topics. Imagine a good deal of laughter enlivening our conversation.

Hyperallergic: How did Disguise the Limit come about?

John Yau: I went to the University of Kentucky [in Lexington] to give a lecture on artist collaborations and I was showing collaborations by Joe Brainard, Norman Bluhm, Robert Creeley, and others. At some point when I was preparing the lecture, I said, “Oh, I should throw in a few of mine.” At the end of the talk, [museum director] Stuart Horodner said, “I didn’t know you collaborated. Have you done a lot of these?” And I said, “Yes, I’ve done many,” and told him some of the other artists that I had worked with. He visited me in New York City, and as he was going through a box of them, he said, “I want to give you a show.”

H: When was that?

JY: About three years ago. And then the idea became bigger as I remembered different artists I worked with. I kept saying, “Oh, I found something else.” Even now, the show’s not complete. I didn’t know I had done so much.

H: I remember you saying that you still had things filed away.

JY: A student of mine at Bard, Julianne Swartz, wrote me recently. She and I collaborated when she was at Bard. I had forgotten about it. I did works with John Lees, a wonderful artist, but I could not find where I put them.

H: Well, that might be in the next iteration.

JY: I would like to think so.

H: There’s a wonderful quote from you in the catalogue, “I’m into every way a poem can be done.” How does that attitude apply to your collaborations?

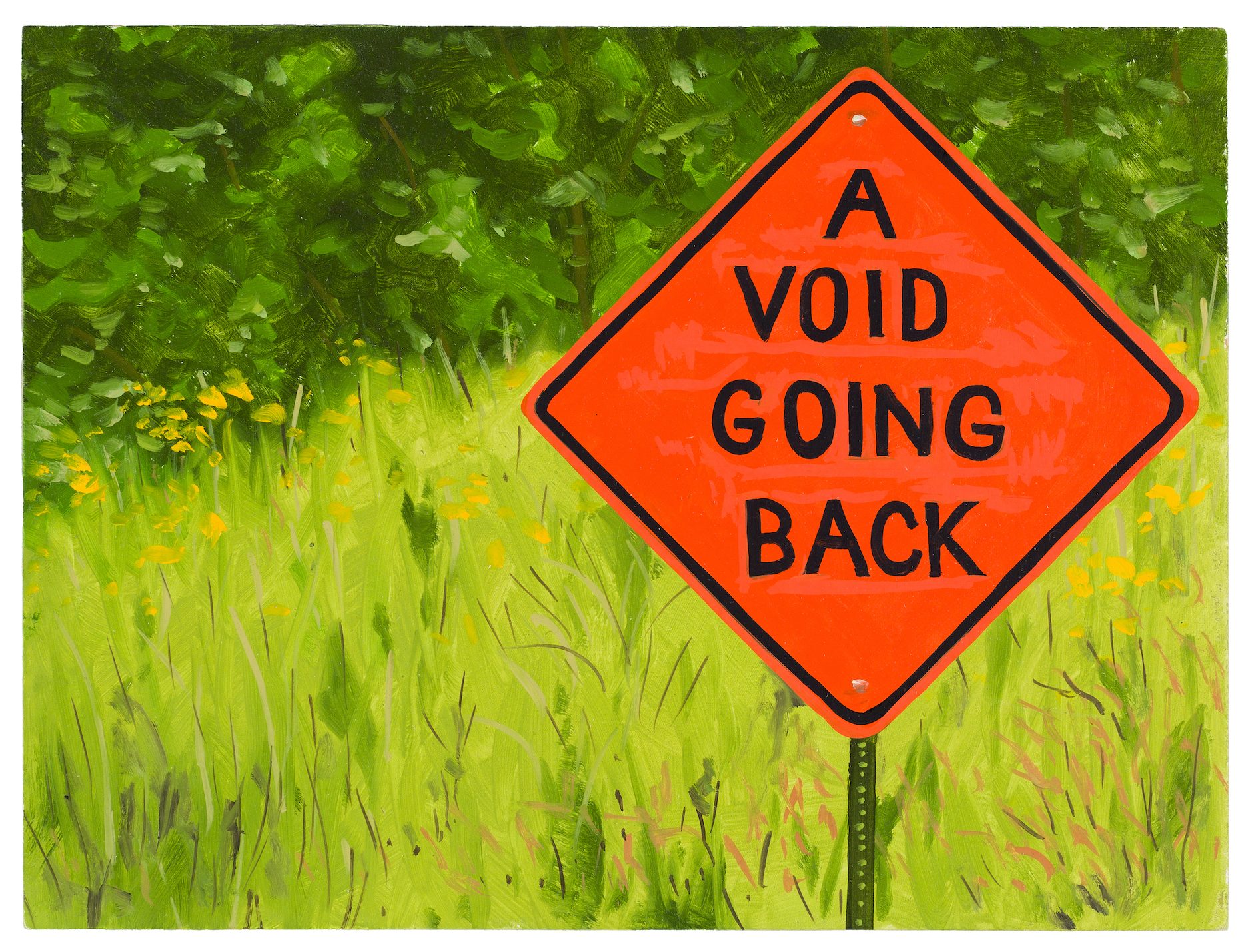

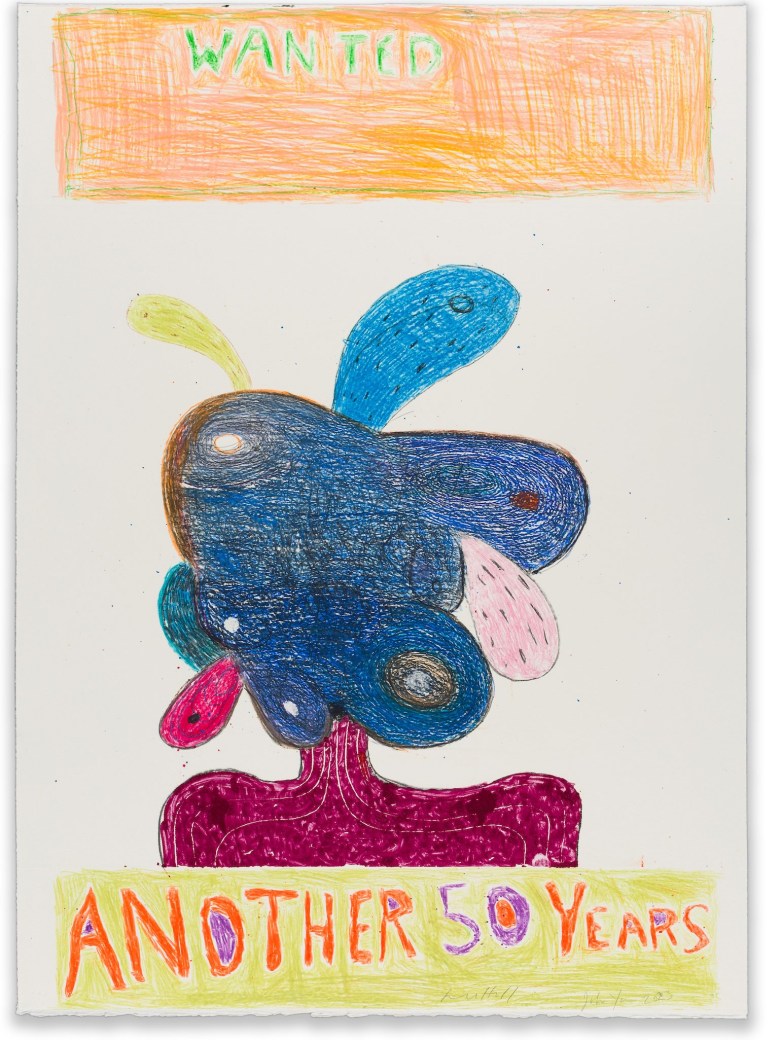

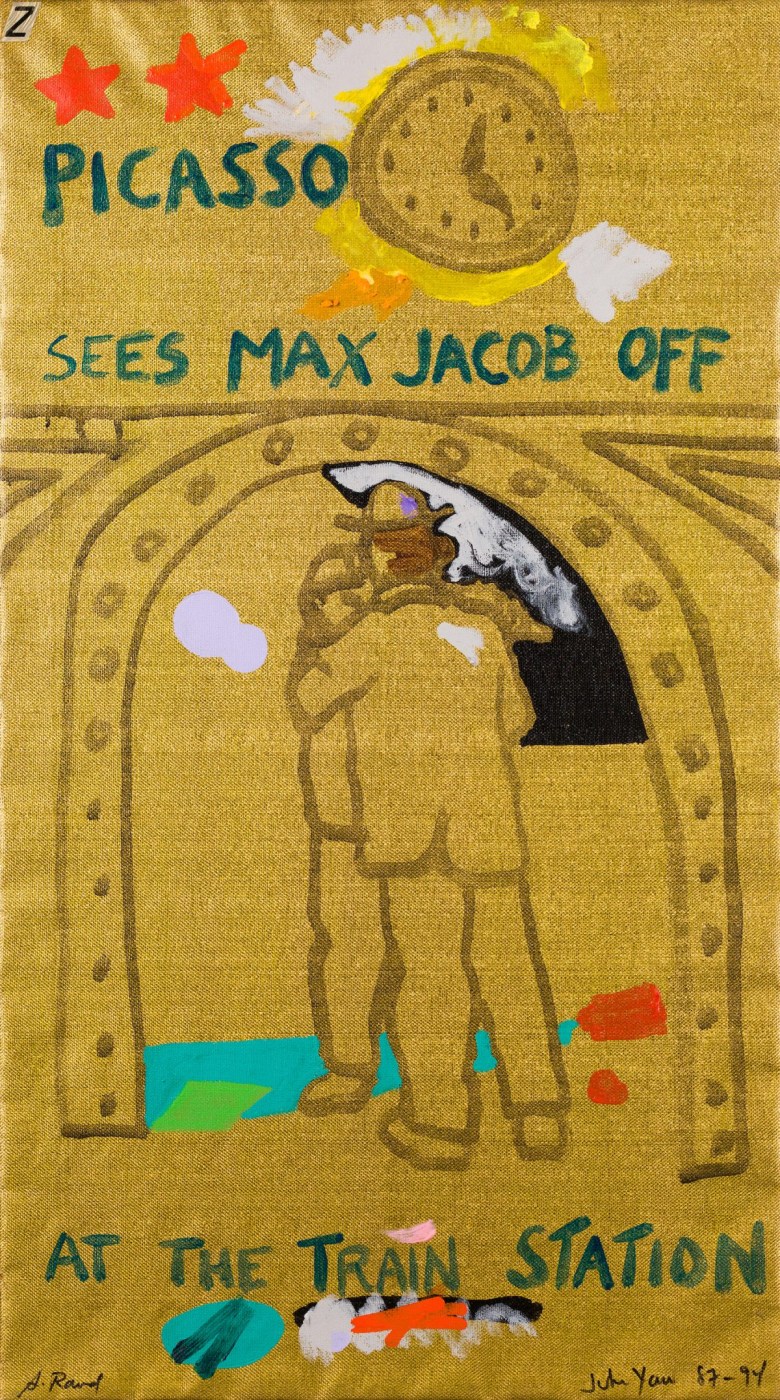

JY: I’ve done road signs, ransom notes, and imaginary bars with Tom Burckhardt. I did a set of alphabet poems on gold fabric [with Archie Rand] that were based partly on imaginary movie posters from the ’30sand ’40s. I did “Wanted” posters with Richard Hull. The prompt can come from either the artist or me. I am usually thinking of the different ways language is framed in society, and how a poem could be slipped into that format. When I first collaborated with Archie Rand, I thought of ABC children’s books — “A is for” — but of course I decided to muck ’em up. I also thought of bad book title jokes I’d heard when I was a child, like Yellow River by I. P. Daily. I am interested in the way language circulates in our society, from high to low.

H: In his foreword to the catalogue, Stuart Horodner states that collaboration is a boundary-pushing activity built on trust and curiosity. How does that fit your experience?

JY: I think you have to trust whatever’s going to happen with the other person. I’m not writing poems in a conventional sense. I’m playing around with language and seeing what it can do. Words are made of sounds. What is the relationship between reading, hearing, and seeing? It’s trust, yes.

Like when I was working with Richard Hull, I would say, “This is what I’m gonna write,” but I didn’t know the image he was gonna come up with. Or with Tom [Burckhardt], I would send him the road sign. I would have it arranged how I wanted it. But once it was sent, it was up to him what he did with it.

In one case, it became really interesting. I worked with Richard Tuttle, and he wanted a poem. The book was being printed at Rutgers [where I teach]. I figured I would go see what he’s up to. So I asked the printmaker, “Can I look at the book that Richard’s working on?” He said, “Richard gave me explicit directions. You’re not allowed to look at it until it’s done.” I go, “Okay,” and that was that. Richard did ask me, “Can I do whatever I want to your poem?” I said, “Yes, as long as you don’t rewrite it, it’ll be fine.” And then I let him have it — and he didn’t rewrite it.

H: Do you remember your first collaboration?

JY: The very first one, I think, is the cover my girlfriend [at the time], Rae Berolzheimer, designed for [my] early book of prose, The Sleepless Night of Eugene Delacroix (1980). But my first deep collaboration was with Archie Rand. We were both at Bard College. We were at this critique with art students and faculty, and we were getting bored. So we started passing notes back and forth about different kinds of dog food — art critic dog food, whatever — kind of making fun of what was going on. At some point I said, “We should do a real collaboration.” Archie said, “Alright, we’ll do a thousand.” I was like, “Oh, geez, why should we do a thousand?” I mean what seemed like something casual and fun was going to become tedious. And then he said something that I thought was pretty important: “We’ll get beyond anything we know how to do.”

That was an interesting measure, going on till you run out of things you know how to say, but you don’t stop. Pretty quickly, you reach: “What am I gonna write?” And you keep going. That was great because it shook me up in terms of my own writing, gave me permission to just keep going.

H: So that’s one of the benefits: a collaboration can push you beyond your normal routine?

JY: Right. And then the arrangement of the words on the page makes you think about how the line functions. You can play with what happens in the arrangement of the words. You can take words apart, like “avoid: a void,” or play with them: “sacrifice: sack of rice.”

H: Poet-critic Bill Berkson described collaborations as hands-on or hands-off. Have you found this to be true in your partnerships?

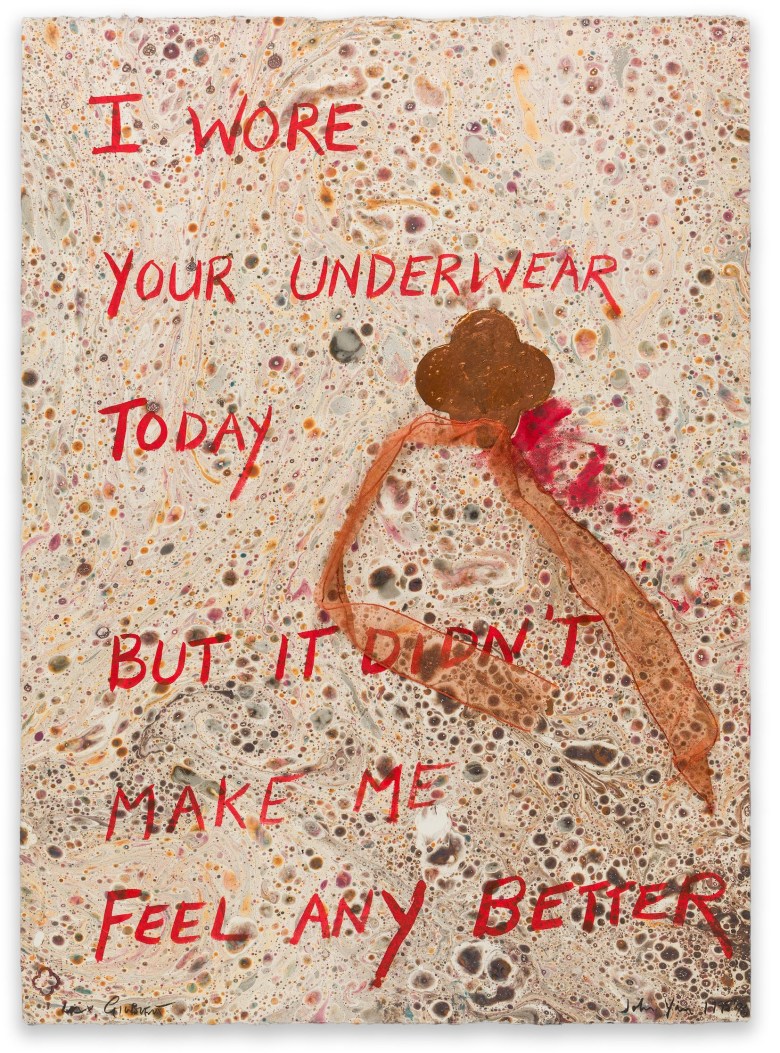

JY: Oh, yes, especially the ones where I’m in the studio or wherever with the artist and we’re working at the same table. In Max Gimblett’s studio, he was handing me sheets of paper.

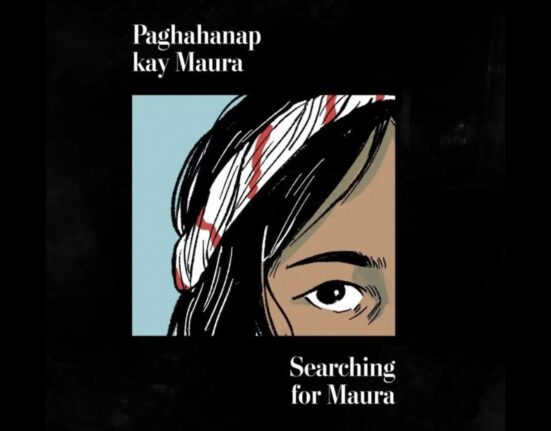

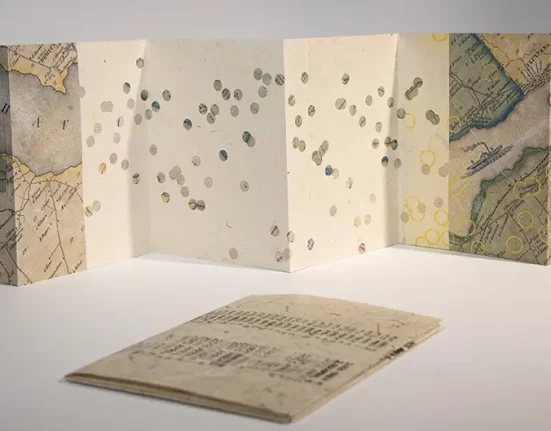

And then there’s the kind where it was done all through the mail. With [Paris-based artist books publisher] Gervais Jassaud, I would send him a poem that he would want to publish as an artist book. He would find the artists, and then they would be given the book, and they had to hand-draw or hand-paint in it. But I didn’t know who the artists were. I didn’t know what was going to happen.

H: You have quoted Robert Creeley saying that collaboration helps you to get out of the habits of your own thinking. Do you have an example of that?

JY: It’s just writing faster and daring to make nonsense, trying to write different ways, being playful with language. All of these things came about in my own work because of something that might have happened during my collaborations.

Sometimes the artist gives me a prompt. For instance, there’s an example in the show. Tom Burckhardt said, “I’m collecting these letters and I want you to write a ransom note.” Suddenly I have to think about how to write an interesting ransom note that is less than 50 words. These prompts got me to think differently.

H: Do you have a Robert Creeley story you could share. I know you visited him in Maine back in the day.

JY: I studied with Creeley. I wasn’t enrolled, but he taught at Harvard in 1972 in a summer program. He came over one day after class. Everybody had left, and he said, “Do you want to go out and have a drink?” I was so nervous. I said, “I don’t drink.” Year later, I was working in Books & Co. [in New York City] and he came in. The man who ran the bookstore said, “This is John Yau. He’s John Ashbery’s favorite student.” He was kind of putting me down. Bob’s instant response was, “Oh, I thought you were my favorite student.”

The guy didn’t know what to say. I thought, wow, Bob has an incredible memory. He remembers me being in this one class for like five weeks and hardly talking to him. Maybe a year later, we were talking about meeting in the bookstore and I said, “Bob, you were so nice to me at that moment. I couldn’t believe you remembered me as your student.” He said, “I didn’t remember you. I just knew that was the right thing to say.”

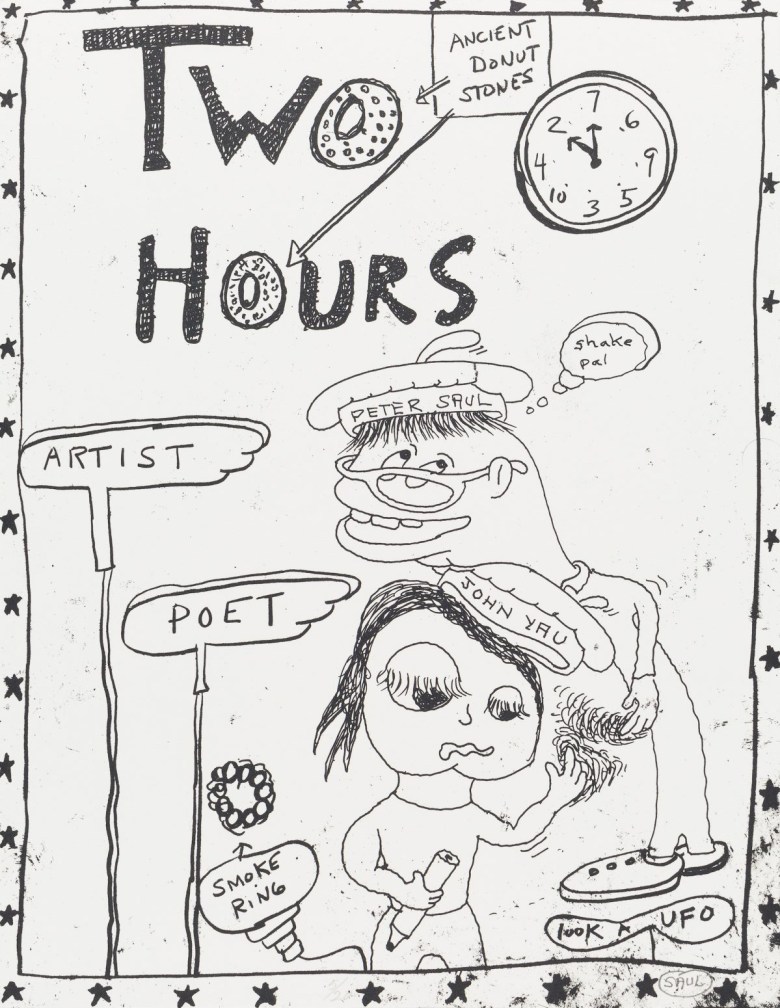

H: Your collaboration with Peter Saul had some interesting twists and turns.

JY: I was invited to be a visiting art critic at the University of Texas in Austin and there were two people there I was dying to meet. One was Peter Saul, whom I had written about, but had never met. The other one was Christopher Middleton, a great poet and translator. I got to meet them both.

I went to one of Peter’s classes where I critiqued his students. We were hanging around afterwards. One of the printmakers, Ken Hale, said, “You guys should do something together.” I think we had two hours before Peter had to teach and I had to be somewhere else, so that’s why the portfolio is called Two Hours.

Peter’s rule was, “You have to draw because I want to write.” I said, “You want me to draw? I can’t draw for beans.” You can see there are two different kinds of handwriting in the work. And there are Peter’s drawings and my clunky things. He let me draw over his drawing; he’d make a figure and I would do something around the figure. He was completely open to this.

H: In a lot of the work in the show, one gets the sense that you’re having a lot of fun.

JY: I am having a lot of fun.

H: Can you share an example of a really fun collaboration?

JY: There were some with Archie [Rand] that were just hilarious. When Archie and I were doing the [alphabet] paintings and I was thinking of movies, I had the idea of having Harry S. Truman and [Chinese-American actress] Anna May Wong star in the same film. I thought that was pretty funny. I think people got the joke, but there’s a point where you’re just trying to entertain yourself with some preposterous proposition, which says something about what it’s like to live in America.

H: Speaking of movies, I was reading in the chronology at the back of the catalogue and it said that you went to a lot of films when you were growing up in Boston.

JY: My mother and father never wanted to hire a babysitter, and they didn’t want me around the house. They would bring me to a movie theater and pay the usher 10 cents to make sure no dirty old man sat next to me. They would come back three or four hours later. They did that many times.

They also, for some reason, didn’t want me to see children’s movies, and brought me to mostly war movies and westerns. I remember seeing weird movies at eight, nine years old. I think I remember seeing Moby Dick by myself because my parents brought me and left me there. Butterfield 8 I saw — of course, I didn’t know what was going on.

I saw a lot of World War II movies. But I think my parents, as I remember it — and I might be wrong, or my psychiatrist might say I’m wrong — they would only bring me to ones in which Americans were fighting the Germans. They never brought me to ones where Americans were fighting the Japanese. I think they were pretty smart about that.

H: I like what Barry Schwabsky wrote in the catalogue. Looking back to Manet and Mallarmé, he calls your collaborations a reflection of your capacity for friendship.

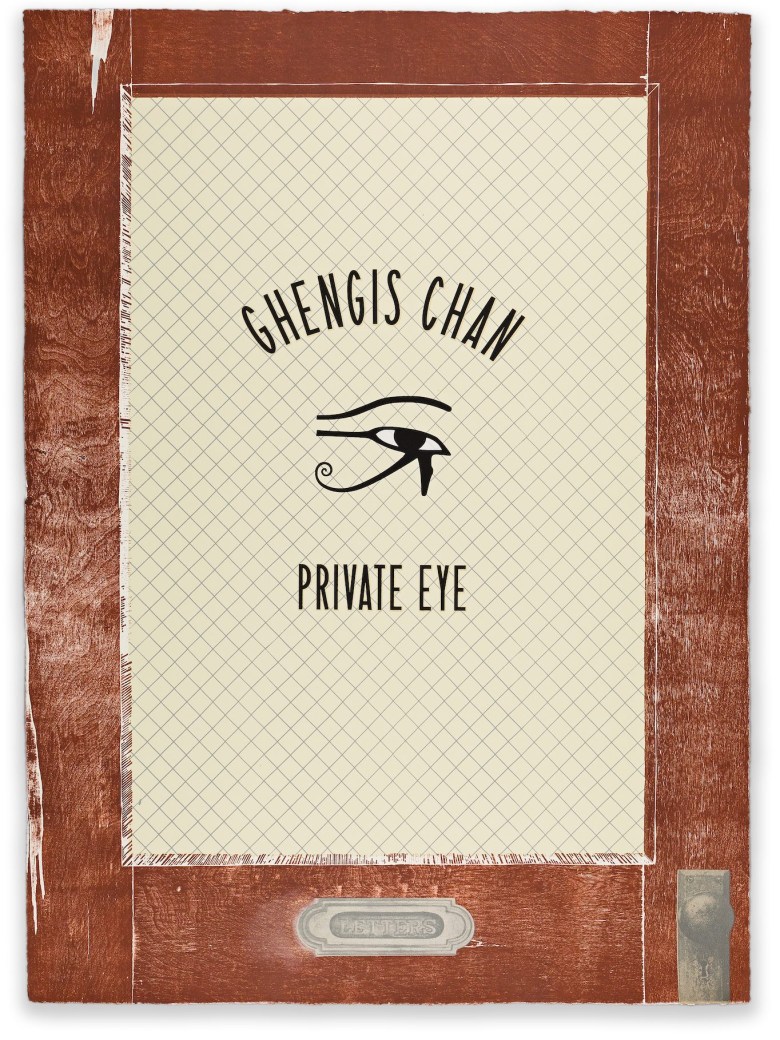

JY: Some of my collaborations were with students where I liked what they were doing. Enrique Figueredo is a wonderful printmaker. I saw his prints at [Rutgers University] where I was teaching. I said, “Oh, this guy’s good,” so one day I told him I really want to have a design for a detective’s door and asked him if he could do it as a silkscreen.

After he agreed, I gave him certain rules. He misspelled Genghis Khan as Genghis Chan. I decided not to correct him because I thought, it’s his collaboration if it’s his spelling. So there are funny things that happen that I just let go.

H: I wanted to ask you about the beekeeper’s uniform in the exhibition. How did that come about?

JY: Barry Schwabsky and his wife, Carol Szymanski, started something called Emergency Eyewash in 2015 and they asked if I could write something to be put on patches. I thought, “Great, I’ll make some money selling patches. I’ve never done that before.” I came up with these funny little patches while they figured out the images to go with them. Then at some point, they asked me to design a piece of clothing. I think other people took it more seriously in the sense that they designed something that could actually be worn on a daily basis. I decided to design a beekeeper’s uniform or I said I want a beekeeper’s uniform. I don’t know why. And that’s what they came up with. It was pretty wild.

H: There’s some fun wordplay in those patches: “Say Crud Groaned,” “Flee Advice.”

JY: Yeah. Thank you.

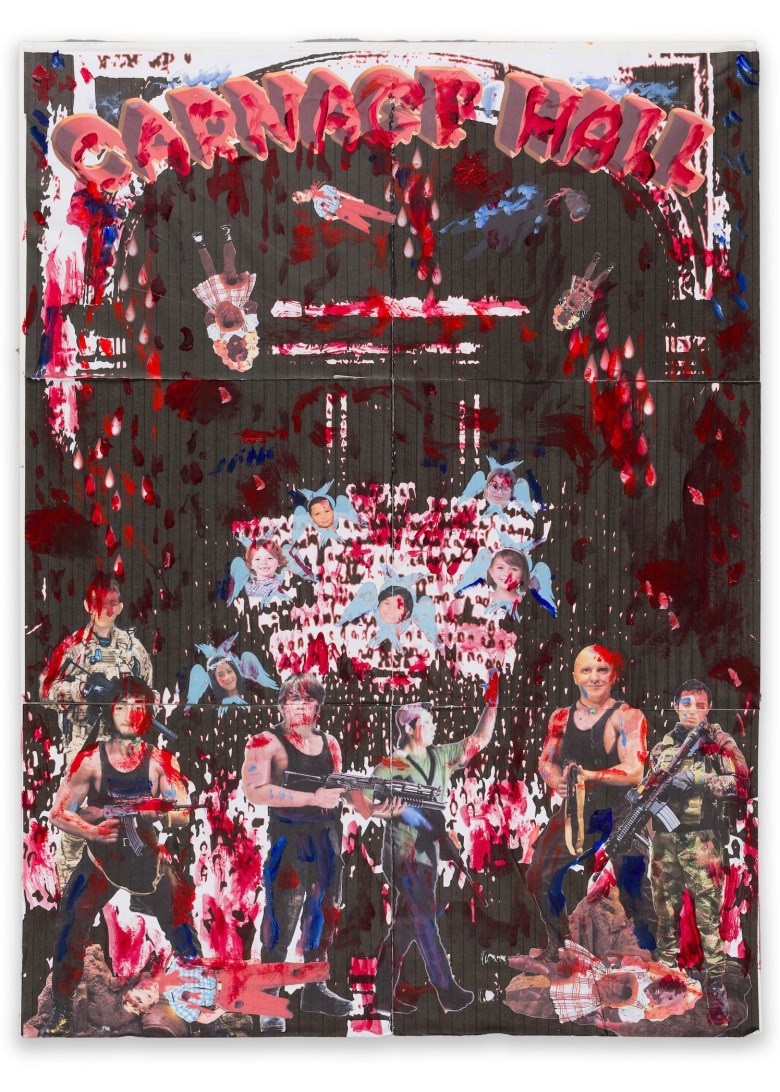

H: The collaboration that you did with Phil Allen struck me because of the serious subject matter, gun violence.

JY: I have written poems about gun violence, usually based on something said by a politician: “We’re with you” or “Our hearts go out to you.” We’ve all heard these clichés and they become meaningless. The gun violence goes on, and the next person is going to say, “Our hearts are with you,” which we know is not true because they don’t have a heart.

Phil and I have known each other for 40 years and we’ve often talked about collaborating. At one point, in the midst of a lot of school shootings, I said, this is what I want to do. I had been thinking about Carnegie Hall, which became Carnage Hall. I sent it to him.

If you’re going to respond to gun violence, you don’t want to exploit it. You don’t want to make it into a cliché. You don’t want to prove how sensitive you are — as if somehow you’re more sensitive to it than anybody else. I sent it to Phil and then he sent me back the collage.

H: Do you have any collaborations in the works?

JY: Yes, with the artist Eric Aho. The Song Cave had come out with a selection of Charles Burchfield’s notebooks, and they’re really beautiful. I said, “Let’s do one.” And then he said, “It has to all be in viridian because that’s the color I want to use” — a weird, interesting green. So we went to his studio the next morning, and I had, the night before, written down a few phrases from looking at the Burchfield journals and kind of played around with them. I wrote eight lines, one on each page, and gave them to Eric. A few months later, he came back with something.

H: Will those be shown?

JY: Yeah. Eric wants to make a little accordion book and show it.

Disguise the Limit: John Yau’s Collaborations continues at the University of Kentucky Art Museum (Singletary Center for the Arts, 405 Rose Street, Lexington, Kentucky) through June 1. The exhibition was curated by Stuart Horodner. It will travel to the Schneider Museum of Art in Ashland, Oregon, from October 17 through December 14.