Women in Nigerian visual arts sector have suffered under-representation. In fact, the ratio of male to female artists in Nigeria is imbalanced in favour of men.

In art schools, men are a majority of faculty members. There is equally imbalance in both enrolment of visual art students at various academic levels and graduate turnouts.

The dearth of female artists who’ve achieved the big time, in sales, reputation, academic attention or general acclaim is also obvious.

The disparity between male and female artists in Nigeria is further emphasised by the low participation rates of female artists relative to male artists in organised professional exhibitions.

At the just concluded Fate VII show, which held in Alexis Galleries, Victoria Island, Lagos, non of the exhibiting artists was a female.

Among art collectors, the inequality is even stronger. In economic terms, it is reasonable to say that art production and consumption are dominated by men. Only one woman, Chief Nike Okundaye, has risen past this threshold.

Colette Omogbai, Afi Ekong and Theresa Luck-Akinwale, who were up at the beginning of their career trajectories, unfortunately, did not have a sustained record of professional practice or a body of work that could define a movement.

Omogbai, as an undergraduate at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science, and Technology (now Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria), organised and carried out her first solo show at the famous Mbari Club in Ibadan.

After obtaining a degree in painting in 1965, she moved to Lagos and organised her second show, which was heavily critiqued and tagged ‘unfeminine’.

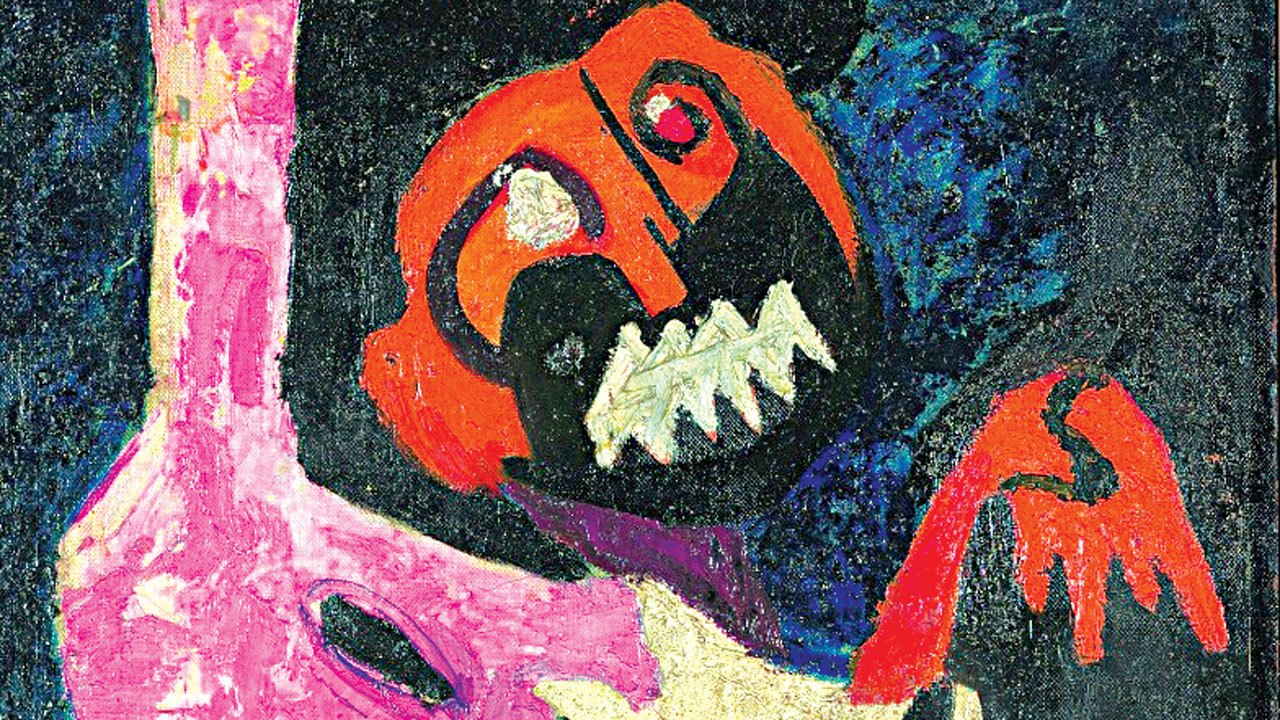

Omogbai responded to her critics in an article, Man Loves What Is ‘Sweet’ and Obvious, which she published in the same year, 1965. However, that was the last recorded exhibition by Omogbai. The only known copy of her works is Agony, which she created in 1963, before the move to Lagos and the subsequent criticism of her ‘unfeminine’ work.

But things appear to be changing very fast. More passionate and vibrant female visual artists are storming the barricade lately than they have ever done.

They are doing amazing work and garnering recognition from within and outside arts circles.

Since Sinmidele Adesanya blazed a trail with Mydrim Gallery, a great number of women are becoming curators and gallery owners, and most importantly, galleries are featuring women-themed shows, even the ones curated by women. They are no longer ‘playing catch-up’ after years of invisibility or filling the numbers.

One other woman whose contributions toward structural changes in the female visual art landscape cannot be ignored is the late Bisi Silva. The curator, for over two decades, through her Centre for Contemporary Art, in Lagos, provided a platform for the development, presentation and discussion of contemporary Nigerian visual art and culture.

Silva curated numerous exhibitions. She served as artistic director at the 10th Bamako Encounters in Mali (2015), co-curated the Dak’Art Biennale de l’Art Africain Contemporain in Senegal (2006) and acted as juror at the 55th Venice Biennale (2013).

In 2010, she founded Àsìkò, a pan-African roaming art school. Àsìkò, which can be loosely translated as “time” in Yoruba, addresses various themes that shift across temporal registers, investigating relationships between history, aesthetics, the materiality of art, as well as documentation and archival practices.

Àsìkò focuses on integrating theory and practice and seeks to create new models for radical art education with models that will foster reflective art and make it relevant to local contexts.

Silva’s work in reshaping artistic and curatorial pedagogies in Africa runs parallel to work by other women artists, curators, researchers and creators on the continent. The female artists are questioning the society and how they fit into this contemporary environment. Their work explores the discourse between western women versus African women, male versus female, tradition versus modernity, and local versus global.

Some of the women who are shaping Nigerian visual art are:

ARTISTS

Peju Layiwola

Layiwola works in a variety of media and genre. She has built on the artistic tradition of her mother, Princess Elizabeth Olowu, the first female bronze caster in Nigeria, a status she achieved through resilience in a culture that is very patriarchal.

Her dual Yoruba and Edo heritage and history has inspired her professional practice.

Her works comprising installation and prints have been exhibited in Nigeria and outside the continent.

Layiwola, who initially began working with metal, now explores a broad range of media that engage with history, memory and cultural expropriation.

In her most ambitious solo exhibition, Benin1897.com:Art and the Restitution Question held in 2010, Layiwola’s returned to the notorious British Expedition of 1897 and the plundering of prized cultural artefacts looted from the bedchamber of her forebears brought together her personal and communal history. Her other collaborative public project, Whose Centenary? in 2014, is also informed by history and the archives.

Of her work and inspiration, she says “I got a lot of inspiration from my mother, having seen her as a young girl casting in metal. So, I opted for metal design at the University of Benin, which was broader spectrum from what she studied because she did metal casting under sculpture. But I specialise in metal design, which incorporates jewelry production, metal casting etc.”

Ndidi Dike

Dike works in sculpture and mixed-media painting. She is one of Nigeria’s leading female artists.

Dike’s experimentation with form led to the sculptural offering Dwellings, Doors and Windows in which she appropriated harbour pallets; she then broke them down to reconfigure the materials in a manner that evoked the Middle Passage.

Peju Alatise

Alatise’s work was exhibited at the Venice Biennale’s 57th edition, themed Viva Arte Viva (Long Live Art). Alatise, along with two other Nigerian artists, Victor Ehikhamenor and Qudus Onikeku, were the first Nigerians to appear at the art exhibition. Her work was a group of life size figures based on the life of a servant girl.

She began her art career with painting, then branched out to being a multimedia artist, using beads, cloth, resin and other materials. She now works in sculpture, using her art to make statements about social issues, while incorporating literature, symbolism and traditional Yoruba mythology into her works.

She also uses media such as bead making, visual arts consultancy, creative writing, leather accessory designing, and interior designing.

Alatise strives to visualise social issues of her country and personal experience. Considering the strongly held social views of gender roles in Nigeria, it is not surprising that much of her artwork focuses on gender inequality and women’s rights.

Nkechi Nwosu-Igbo

Nkechi is a poet, installation artist and painter. She was inspired by the works of Obiora Udechukwu and Olu Oguibe. She started exhibiting quite early and has been involved in over 80 shows as an artist and in curatorial roles.

For over a decade, the artist has consciously made her works and impact on the art global space felt in a multidimensional ways. Her works have continuously reflected the educational system of Nigeria. Her installations are known for their very high level of critical activism and social obligation.

Nkechi is a thoroughbred artist who has become a model today for aspiring female artists to look up to. She succumbs to neither stress nor fatigue, rather they are complements to be on the driver’s end of the wheel.

Fatimah Tuggar

Tuggar, through her digital work, investigates the cultural and social impact of technology.

The Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Art at the Ontario College of Art and Design University creates images, objects, installations and web-based instructive media artworks that juxtapose scenes from African and Western daily life. This draws attention to the process involved and considers gendered subjectivity, belonging, and notions of progress.

The objects usually involve some kind of bricolage; combining two or more objects from Western Africa and their Western equivalent to talk about electricity, infrastructure, access and the reciprocal influences between technology and cultures. Similarly, her computer montages and video collage works bring together both video and photographs she shoots herself and found materials from commercials, magazines and archival footage.

Meaning for Tuggar seems to lie in these juxtapositions which explore how media affects daily lives.

Juliet Ezenwa Maja Pearce

Ezenwa was first introduced to art forms by her grandmother, a reputable traditional body decorator using uli, the art and style adopted and made popular by the Nsukka School.

She was initially known for her sober watercolour paintings of landscapes and women. She participated in Tom Lynch’s Water Colour Rescue Workshop, and her landscape painting, Straying Goats, is published in his book, Great Watercolour Rescues.