Most people know Diane Huling as a pianist. With bachelor’s and master’s degrees in piano performance from the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, N.Y., Huling, 69, has performed internationally. In a parallel career, the Cabot resident — a Vermonter since age 16 — taught at Dartmouth, Lyndon State and Johnson State colleges, retiring in 2008.

Huling has also painted since childhood. For the first time, that pursuit is in the spotlight, with a solo exhibition titled “Strands: Stories, Music and Meditations” at the First Congregational Church in Berlin.

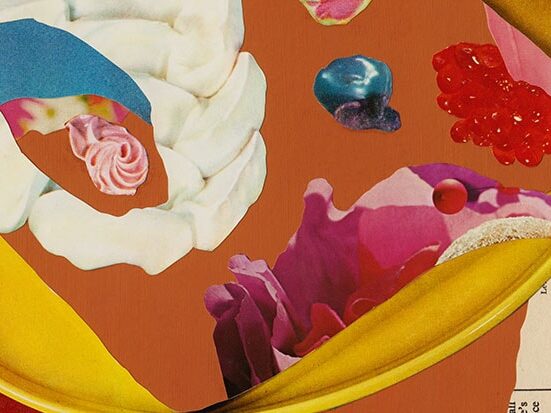

Some audiences may have seen Huling’s storybook-like paintings on two former occasions. For a 2012 recital, she illustrated the 11 movements of Modest Mussorgsky’s “Pictures at an Exhibition” — an 1874 composition intended to serve as a musical tour of 10 paintings by the composer’s friend Viktor Hartmann. And in 2018, Huling made paintings of William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night for a production of the play at Lost Nation Theater in Montpelier.

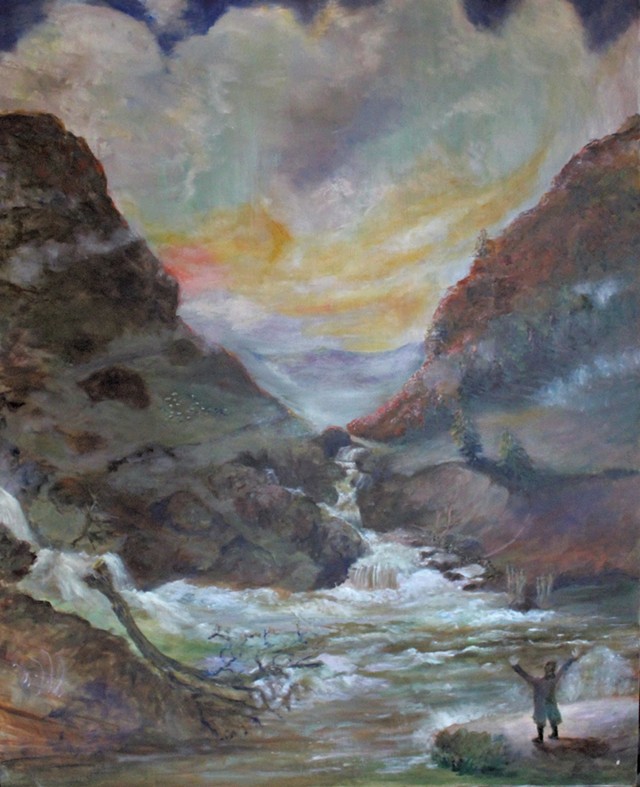

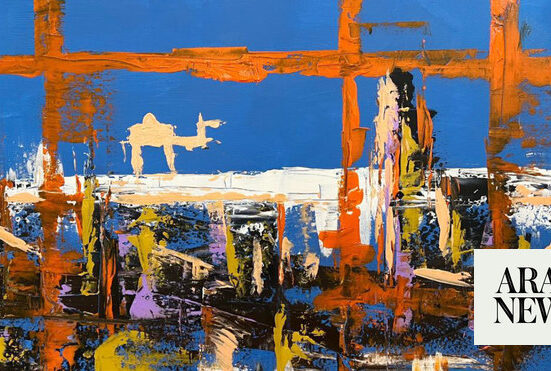

Huling met up with Seven Days at her exhibition, which includes works from both those series along with new paintings. Citing influences such as J.M.W. Turner and the contemporary trompe l’oeil painter Graham Rust, Huling paints in oil on panel or canvas in her home art studio — the same room that houses her Steinway Grand Model M piano. In an ongoing project, she’s painting her interior walls with murals in a 16th-century Florentine trompe l’oeil style in honor of her Italian-born former piano teacher.

Huling later chatted by phone about her artistic background and views on art versus music.

How did you start painting?

My mother had five children and was very busy, and she wanted to make sure we weren’t bored. She was a piano teacher, so she gave us all piano lessons and had us choose an additional instrument. I chose flute and couldn’t stand it; I went back to piano. [When I was] around age 10, she cleaned up the shed [in Connecticut] and … made it into an art studio for me. My dad gave me paints. It was something to keep me occupied; it was that simple.

Why did you want to mount this exhibition?

It’s a preamble for a concert I’m giving at Barre Opera House in May or June [which will show artworks based on what she plays]. The program will include the last sonata of Beethoven, so that painting [“Beethoven, Sonata in F# Minor, Op. 111”] will be there. The rest will all be new. I have about 18 paintings to do for that. There are nine different pieces on the program.

Why do you want to hang paintings about music at your recital?

It’s a way of illustrating the music in a way that might connect with a bigger audience than the audiences that normally go to a classical music concert. They’re in the form of illustrations and explanations, but they’re also a deepening of the meaning and understanding of the pieces for me.

I was just reading Johann Sebastian Bach: Life and Work by Martin Geck, and this [combination of painting and music] was an absolute no-no in 1700. It was a fight back then and still is. After religious music, there was this Romantic idea of “absolute music”: People believed that music should stand alone, that illustration would make the music insignificant.

But everybody absorbs things in a different way: Some people are aural; some are visual. From my teaching, I learned over and over that I could get to students in different ways. For example, I’ve had these three young, talented siblings who were taking piano but had a wide range of interests and talents, and when I started connecting them to those things they loved doing — visual art, reading, singing — their piano playing got much better. One of them loved improvising, so then they all started improvising together at the piano.

It doesn’t sound like your typical piano lesson.

It never has been. Sometimes I think I scare the parents because I go off on these tangents.

So, you understand music visually?

It’s not that I understand music visually; I connect the emotions between the visual and the aural. There’s no piece of music I don’t connect to [in that way]. There’s not a specific image that a piece drives me to. It’s the emotional connection that creates the visual.

There are basics in all the different arts — light, movement, color, structure. The part I’m glorying in right now is to find all the connections between these two arts. [For example,] I’ll play the Bach C Minor partita at Barre Opera House, and right now I’m doing six paintings where different flocks of birds in flight will represent the voices of the partita.

Can you talk about the small triptychs grouped on one wall?

That’s a new project. I’m creating small, handle-able — I don’t know what word you’d use — triptychs based on musical works for meditation purposes. They’re portable, or small enough to fit on somebody’s meditation table or office desk. I started with [Frédéric] Chopin’s Nocturne in D flat Major. Eventually I’ll record [myself playing] the works they represent. You’ll be able to put a triptych on your dashboard if you’re stuck in traffic and getting anxious, and look at it while listening to the music on your phone.

Will painting ever take over from music in your life?

Never. That’s an easy question.