“When you think of the Charleston Renaissance you think of artists like Alice Ravenel Huger Smith or Anna Heyward Taylor,” says Chase Quinn, a curator at the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, South Carolina, of the art movement that defined the city between the World Wars. “Their works are floral, romantic visions of Charleston, really inspired by French Impressionism or Japanese woodblocks.” So when Quinn began studying one of their contemporaries, Edward “Ned” I.R. Jennings, he immediately noticed the stark difference in Jennings’s surreal landscapes and bold, whimsical figures. Quinn realized that Jennings was drawing from entirely different inspirations: British Aestheticism—a late-nineteenth-century art movement closely associated with the playwright Oscar Wilde, created in response to the ugliness of the Industrial Revolution—and the British illustrator Aubrey Beardsley.

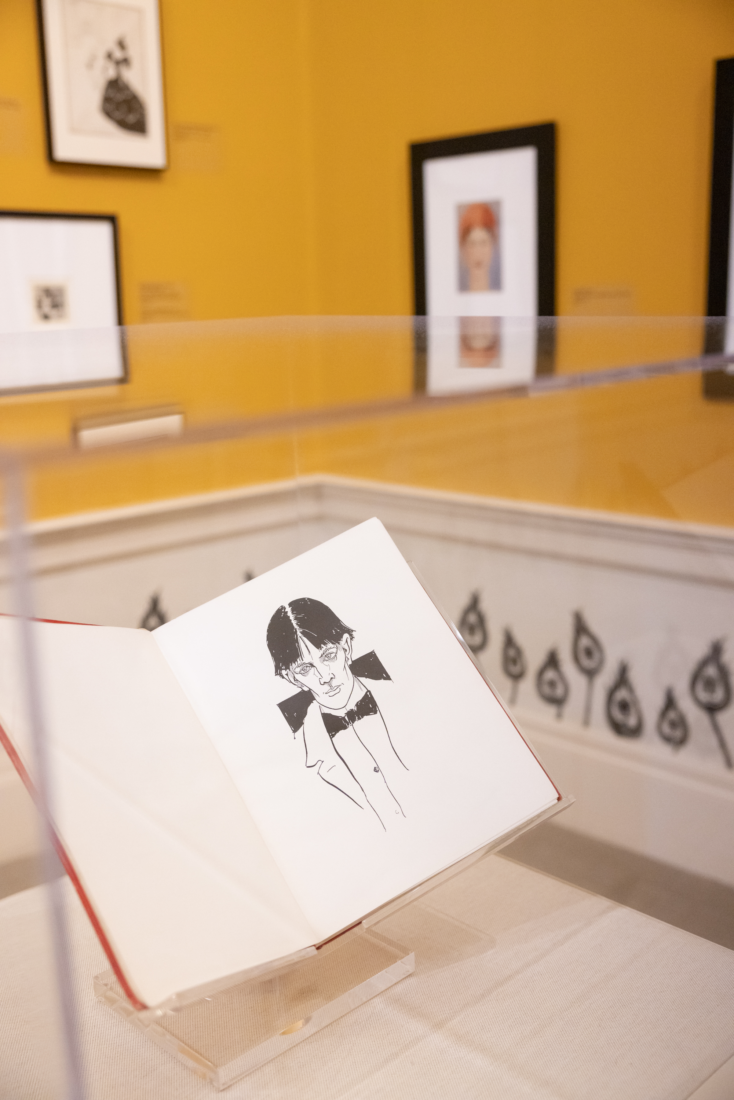

Aubrey Beardsley’s 1892 Self-Portrait.

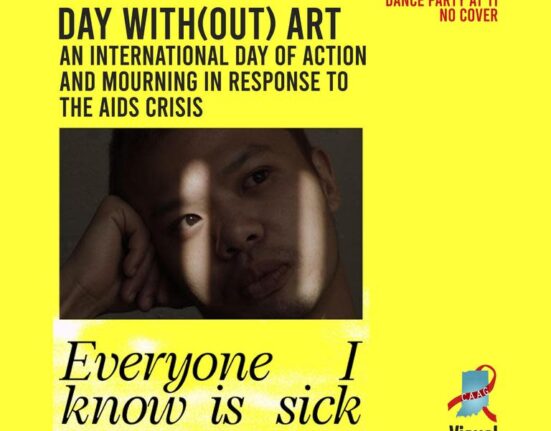

In Something Terrible May Happen (through March 10), the Gibbes displays some forty works by Jennings and Beardsley, highlighting, as Quinn says, “the influence and tradition of the queer aesthetic from the turn of the century to the twenties in Charleston.” Take Jennings’s Costume Design for Princess’ Slip, for instance, a colorful caricature of a robed woman with fiery hair, glancing coquettishly over her shoulder, or his 1929 Egyptian figure, bedecked in blues and golds against a bold banded background, both of which “embody the themes of the exhibit like eroticism, decadence, and humor,” Quinn says. These images appear alongside sketches by Beardsley, on loan from such institutions as the Harvard Art Museum, Princeton’s special collections, the Matisse Foundation, and Washington College.

Jennings’s 1929 untitled Egyptian figure.

In fact, it’s from one of Beardsley’s illustrations on display that the exhibition gets its name. Beardsley drew The Black Cape, depicting a seductive witchy figure in a billowing black dress, as part of his illustrations for the first English edition of Oscar Wilde’s one-act play Salomé in 1984. In the biblically inspired play, Salomé is the stepdaughter of King Herod, and in many interpretations, she is said to represent the temptation of art and beauty. “You are always looking at her. You look at her too much,” a character tells a young captain, who has fallen under Salomé’s allure. “It is dangerous to look at people in such fashion. Something terrible may happen.”

Chase Quinn.

But the young captain looks anyway, and Quinn would advise you do too, as looking at and learning about these often misunderstood pieces will illuminate a previously unexamined side of the Holy City’s history. “This exhibition coincides with our desire—and also the climate across the country,” he says, “to tell more broadly the narrative around visual art.”