Beginning at 12, Luz Helena Thompson identified herself as a writer. She documented her life through writing and enjoyed using words to paint pictures. She later discovered her passion for visual art while grieving the loss of her grandmother. Her journey as a visual artist began with repurposing a broken mirror and evolved into a practice focused on glass mosaics. “To be a visual artist has brought me joy and given me an opportunity to heal,” she said. “I get to use broken pieces and make something absolutely beautiful out of all that brokenness.”

While working as an artist and teaching middle schoolers, she became interested in teaching and building a career as a practicing artist. Among the body of work she is most proud of is a mask collection symbolizing the invisible wounds of service members, addressing topics such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and military sexual trauma (MST). Her personal experience with MST and mental health therapy inspired these powerful pieces.

Thompson is passionate about art as a therapeutic outlet for veterans’ healing and storytelling. Through her teaching, she utilizes design thinking for creative expression, encouraging veterans to create meaningful projects. She emphasized the importance of being trauma-informed when working with veterans. “As a veteran, I feel a deep sense of responsibility to create classes that address the unique experiences of veterans,” she said. “It’s important to me that the veteran community have increased access, equity, and opportunities to participate in creative arts programs.”

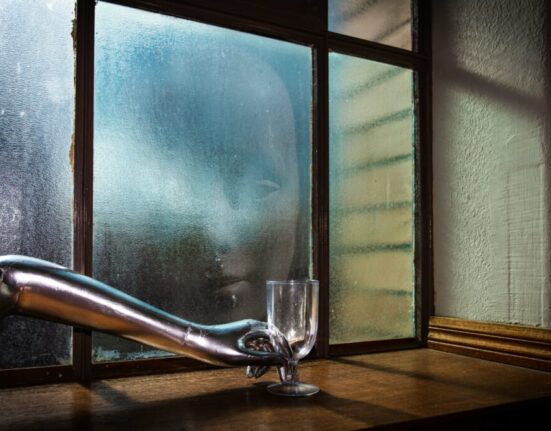

Luz Helena Thompson works on a glass mosaic in her studio. Photo courtesy of Luz Helena Thompson

NEA: Tell me about your military background.

LUZ HELENA THOMPSON: I am a United States Marine Corps veteran. I went into the Marine Corps shortly after high school in 1998. I volunteered for my first overseas duty station in Okinawa, Japan. And that is where I spent the remainder of my enlistment.

NEA: How and when did you become interested in visual art?

THOMPSON: I have always been a writer since I was 12 years old. I picked up a pen and documented my life starting in 1992. I still write. I love writing. My grandmother Irene used to take me to art classes with her. I always tried to do visual art but never felt confident in my visual artistic skills. As a writer, I knew I could articulate what I wanted and paint a picture with words. In 2011, my grandmother passed away. I was super close to her. I was going through the grieving process, and for the first time in my life, I got writer’s block.

Writer’s block was terrifying because I thought this skill I used to manage emotions was gone. At the time, my kids were working on a school project, and I decided to take over the project and paint. Something about painting felt really good. Over time, I was painting and drawing, and after cleaning up one day, I cracked a mirror. My grandma was very superstitious about everything, especially breaking mirrors. I remember crying, thinking I would have seven years of bad luck. Nanny had just passed, and I didn’t know how to deal with it. And at that moment, something hit me, “Maybe I can bypass the bad luck if I just glue this broken mirror to the canvas I’m working on.” And that was the start of working with broken mirrors and glass. Looking back, that was a huge gift.

NEA: What inspired you to become a professional artist?

THOMPSON: My son was going into his first year of middle school at this new school called the Vista Innovation and Design Academy (VIDA), a new charter school. I asked the school’s principal, “I have a master’s in science. Are you looking for teachers or anything that I could do at the school?” And the principal said, “No, but do you do anything else?” I explained how I work with broken glass. And he responded, “Do you think you could teach middle schoolers how to do glass mosaic?” As a Marine, I replied, “Challenge accepted.” Working at VIDA introduced me to understanding design thinking, which is the foundation of everything I do now as an artist, but also challenged me to see if I could learn design thinking and teach glass mosaic making to middle schoolers. Looking back, it was one of the greatest times in my life. I felt so blessed to have the opportunity to learn design thinking and work every single day at making art. I designed murals for the school and then incorporated glass mosaic pieces into those murals. It was like art boot camp. I worked there for two years. After, I realized I enjoyed teaching art. I wanted to find a way to be able to continue teaching but also to progress as an artist.

NEA: Tell me about a piece of art you’ve created that you’re most proud of and why.

THOMPSON: I made a collection of masks that represent the invisible wounds that service members go through. That’s the work that I’m personally most proud of because while going through mental health therapy, I was asked over and over, what does my PTSD look like? What is military sexual trauma (MST)? What does that look like? I was drugged and raped when I was in the military. I reported it, and I was retaliated against for reporting it and ultimately separated from the Marine Corps. After 16 years, my discharge was upgraded. My service was finally acknowledged, and I was eligible for VA benefits. It took a long time for what happened to me to make sense to people. I’ve tried to separate that part of my life and my art. While it does influence it, I don’t want every time that people talk to me about art for it to be about sexual assault in the military.

I made this mask collection that has what rage looks like for MST. I made a recovery mask covered in seashells, and it looked like it was all patina. It looked like it had been pulled from the ocean because my recovery from trauma was in large part due to art but also due to surfing. I spent a lot of time in the ocean healing.

The first class I was asked to teach for Path with Art was a workshop that I called Mask Making for Invisible Wounds. There was an exhibit at Path with Art called About Face, which included my masks and masks other veterans made while taking one of my classes. Almost a hundred percent of the masks we showcased in the exhibit showed the face of MST. For the first time, I didn’t feel alone that I had made MST masks. To see that other veterans, some of whom were also combat veterans, wanted to translate the MST more so than the combat trauma into a mask was profound. As a writer and visual artist, I realized the significance of the impact that art can have when you give people permission to take something that’s so painful and give it a tangible space to live outside of themselves. To step back and see I wasn’t the only one who went through this, and these people who made the masks, these other veterans, it was like they were saying the same thing I was, but just in a different way. It was incredible.

NEA: Often times adults in visual art workshops are reluctant to participate because they think they are not artists. How do you address this in the programs you facilitate with veterans?

THOMPSON: I created a class called Design Thinking for Creative Expression to address this issue. In my first experience working with Path with Art, I was teaching art online to veterans. In the first class, I said, “Hi, nice to meet you. You’re all artists, congratulations.” And everyone responded, “No, I can’t draw. I’m not an artist.”

Design thinking teaches a process to go from concept to completion. I use design thinking to address the problem of people not believing they are artists. The class I created provides basic instruction in project planning and offers a design challenge. People who were doing woodworking or who were doing culinary arts didn’t see themselves as artists. We looked at different mediums they were already working with, and I gave guidelines for a project instead of hard rules. The objective was to create something that was meaningful to them. The last week, everyone presented what they created. Through the class, we redefined what we see as art and how we define an artist, especially a veteran artist.

Design thinking for creative expression is the easiest way to work with any population, especially with veterans who are so used to everything being either black or white. The process gives freedom for people to choose what they want to create, and it is different than military culture where we’re told what we want. The freedom resonates with veterans. Learning a process of being able to go from an idea, the creativity, to ideation, making something, also resonates.

NEA: How has work as a teaching artist and facilitator informed your practice as a studio artist?

THOMPSON: I apply the design thinking process I teach to everything I do. Design thinking allows me to approach new projects realistically. I can effectively map out a new project before I start. I love that there’s a system to everything. I love making mistakes. Making mistakes and completely failing at something is my favorite thing to do. Failing challenges me to look at something differently. And instead of throwing away artwork, I refine my work by asking questions. In the classes I teach and in my personal work, making mistakes is part of artistry, and so is asking the question, “What can I learn from the mistakes I made?” I’ve also learned that the act of teaching art to me is like another medium I work in as an artist.

NEA: What advice would you offer a community arts organization interested in offering programs for veterans?

THOMPSON: It is important to recognize that every veteran has a story. How we tell those stories differs, but each one of us has a unique story that’s unique to our upbringing, our military service, all the things that happened there, and who we became after service. It’s really important to be trauma-informed while working within the veteran community. You could do more harm than good if you approach working with veterans without being trauma-informed. It’s important to understand the unique needs that veterans have. For example, some, not all, are really good about sneaking out the back door. Some may come to a class, and something may come up that challenges vulnerability, and they say, “I don’t know if I’m ready for this.” And then they don’t show up for the next class. And by “sneaking out the door,” I mean that the thought for the veteran becomes, “If I tiptoe backward quietly, no one will notice that I’m not here.” One of the key aspects of working with veterans is that we have to have constant communication between the veteran and the organization. Many veterans do very well with a follow-up phone call that says, “I noticed you weren’t in class last week. Everything good?” It’s important to have a conversation that gives them an opportunity to share that they felt vulnerable and to discuss what class will be like when they come back. I always recommend that people check in with a mental health professional. I believe that less rules are a good thing when it comes to art. We spend our entire careers in the military following sets of rules. Putting all those rules aside when we express ourselves creatively and asking, “What does it look like to you?” is powerful. I find that when you remove that barrier, people experience freedom in self-expression.

NEA: What’s the value of giving military communities access to the arts?

THOMPSON: The first thought that comes to mind is, “What is the value of giving mental health to veterans?” The arts and mental health go hand in hand. We’ve seen over the years that there’s a high value in taking care of not just physical health and wellness but the mental health and wellness of an individual, especially of a veteran. Art has been a lifesaver for me. It has been a form of recovery from trauma. The practice of art and creating something can be such a therapeutic practice that people are often surprised how much they feel better after. In the same way that we value taking care of the physical wellness of a veteran, we should value taking care of the part that unlocks an individual and allows them to be open to sharing stories through their artwork. They have a lot to say.

Santina Protopapa is an arts education leader, musician, record collector, storyteller, and media maker who has been a member of the Creative Forces: NEA Military Healing Arts Network team since 2020.