Matt Clark puzzles over the definition of art as a simple encounter with a painting. The founder of United Visual Artists is drawn, instead, to the way disciplines bleed into each other. How different environments can conjure different selves. In the mid ’90s, Clark came across the work of Bill Viola. The great video artist, who died last month, made installations that fused together sound, light and moving image. He famously believed that technology – a force that disrupts and fragments and divides – could help us better understand the mysteries of human consciousness.

“I saw the Bill Viola show at the Whitechapel

Viola’s work poses questions: Why are we here? What do we owe each other? How do we override the terror of contemporary life to find joy or awe or wonder?

When Clark started out 20 years ago, promoting events, designing records and concerts and books, these concerns had started to simmer under the surface of the culture. They reared up with an intensity unimaginable at the turn of the millennium – that strange period marked by dial-up modems and around-the-clock news channels and the early tendrils of mass surveillance, levelled first at bodies stigmatised by 9/11.

“What we wouldn’t do to have those problems,” Clark says.

At the moment, he’s reading The Coming Wave, the new book by Mustafa Suleyman in which the tech entrepreneur issues a warning about the speed with which artificial intelligence is remaking society. “Things are moving in so many different directions,” Clark says. “There is not even a left or right or up and down anymore. I can’t quite understand the gravity of this new era we are part of.”

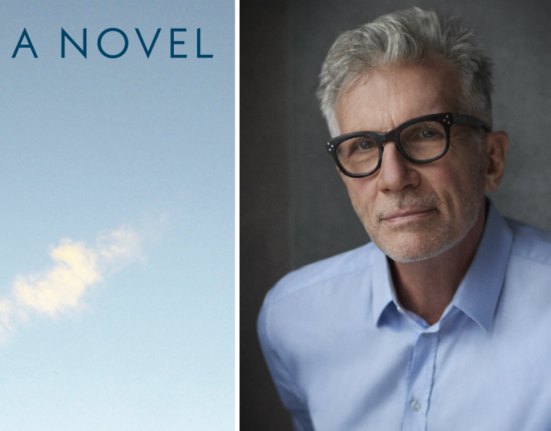

Clark appears on my screen over Zoom wearing a black baseball cap and wire-rimmed glasses. He moves between a boyish, streetwise energy and a kinetic curiosity. He takes time to gather his thoughts. He articulates knotty ideas plainly. Sometimes, he looks away from his computer, as if searching for what flickers in his mind, his attention rippling outward.

This month, United Visual Artists (UVA) will present two installations at Now or Never, a new festival spanning art, sound and technology that will unfold over 17 days across Melbourne, featuring work by the likes of Studio Lemercier and Marco Fusinato. He sends me videos over email and in one, Silent Symphony, eight sculptures revolve in an otherwise empty room, emitting planes of light, their movements growing increasingly animated, frenetic, attuned to an invisible frequency. In the other, Present Shock II, row after row of statistical clocks, in alarm-bell red, flit across a screen that recalls a stock exchange ticker display. The digits appear and disappear only to emerge again in new configurations. They are interspersed with headlines – Images of Trump and Kanye dancing around golden showers, Global snail market value this year – generated via algorithm and plucked from the news, an illusion of authority masquerading as evidence.

“There is so much promise and so much danger,” Clark says. “We’ve had fake news since medieval times but it’s the abundance [of it]. The work is as much about that as it is about the speed of information that we are navigating on a daily basis.”

In 2008, the cultural anthropologist Michael Wesch first used the phrase “context collapse” to describe the sensation of different audiences converging on digital platforms, sparking a form of dialogue that flattens meaning, divorces a message from its origin. To view Present Shock II is to be knocked sideways, unmoored from time and space, stuck in a perpetual “now”, deprived of the ability to discern fact from truth, past from present. It invokes this moment so precisely, I’m almost reassured: maybe my distress isn’t a personal failing but the logical consequence of being cast out of language, of no longer inhabiting a reality with borders that we can agree on.

Present Shock II, which will be presented in a glass box outside Melbourne Town Hall, unfolds to a plaintive score by long-time collaborator, Massive Attack’s Robert Del Naja, himself a renowned visual artist. Clark has thought about this work since he first designed visuals for the 100th Window tour of the trip-hop pioneers, alongside engineer Chris Bird and programmer Ash Nehru, who would go on to become UVA’s founding members.

“We wanted the band to communicate their political concerns,” he says. “It was a form of social media before social media and smartphones. It was 2003 and we were living through the start of the Information Age. We were feeling anxious then. How can you believe anything? It was really about trying to make a snapshot of ‘now’, a barrage that left the audience engaged but also overwhelmed at what they experienced.”

Present Shock II, which premiered last year at London’s 180 Studios as part of Synchronicity, UVA’s 20th anniversary exhibition, represents questions that Clark has been grappling with for two decades, and which have only grown more prescient.

“I wanted to visit some of the ideas that existed in fragmented form in that first show,” he says. “Who would have imagined the world we were going to go into in 20 years, with AI, with automation? It’s hard to believe that things could [become] worse.”

UVA has presented works around the world – from Seoul to Shanghai, Hobart to Barcelona. Clark confesses, with a sheepish laugh, that he has spent his entire life in the same pocket of south-east London. His mother, he says, was a hairdresser; his father, a publican.

“I grew up within a supportive working-class family, but really struggled with my education,” he says. “I had undiagnosed ADHD and dyslexia, so I wasn’t very academic, but had a strong thirst for learning.”

As a teenager, he gravitated towards hip-hop: Public Enemy and N.W.A, alongside electronic music from the 1980s. At school, he could paint. He could draw. He was nurtured by his art teacher.

“I applied to go to Camberwell College and studied a joint honours course,” he says. “You spent half the time learning a design discipline and the other in fine arts. I chose sculpture. I really loved the three-dimensional world of making things. [In my family] just to be a professional in the visual arts and make a living from that seems a ridiculous proposition. But I had no other choice and I’m extremely grateful.”

After college – “because I needed to eat” – Clark became a graphic designer. A long-time music fan, he started working with sonography. A production manager whom he had met while designing a show for the electronic duo Leftfield introduced him to Del Naja. “Massive Attack were the soundtrack to my youth,” he says. “I knew they had worked with these amazing directors and photographers – Nick Knight and Michel Gondry. I knew if we approached it the right way, it could be a springboard to setting up our own art studio.”

In a world obsessed with words like “immersive”, it’s become common for artists to collaborate with technologists, but this was new terrain when Clark, Nehru and Bird began. “We named ourselves United Visual Artists,” laughs Clark, whose co-founders have since moved on to other projects. “Although we were three guys in a little studio in Brixton, it was [as if] we were a big enterprise.”

They started collaborating with some of the best-known musicians in the world: U2, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Jay-Z. Still, there was something missing. “They were huge productions in terms of scale,” he says. “But we became curious about ideas that weren’t in service to other artists.”

Then, in 2006, the Victoria and Albert Museum invited UVA to present an installation in the John Madejski Garden, a courtyard enclosed by 19th century Italianate architecture. Volume, a field of 48 columns that emitted sound in response to movement, reflected the questions that would go on to define the collective: where is the line between artwork and spectator? Are our actions the result of our desires or the rules that govern the spaces we occupy? In the work, lozenges of light turn pink, then green. Orbs hover in the dark, between ground and air. The work shapes and reshapes itself around viewers’ bodies.

“I was interested in ritualistic spaces and anthropological studies,” says Clark, whose 2014 installation Momentum turned the Barbican’s Curve Gallery into a spatial instrument. “[Imagine] that you had told yourself just 10 years ago that people would be looking at a concert through a screen, holding their hands above their heads. It was about how certain parameters can change human behaviour in quite an extreme way.”

In the Information Age, of course, we’re all performers. These times have granted anyone with a smartphone access to an audience, the power to narrate themselves. But Clark is equally interested in the shape of what we fail to listen to. “I went on a trip to the Arctic and remember getting off the boat,” he says. “There was no wind, no trees. The silence was scary and loud.”

For The Great Animal Orchestra – an acclaimed collaboration with Bernie Krause, the bio-acoustician and artist who introduced the synthesiser to popular music – UVA designed spectrograms for field recordings of animals in their natural habitat. Krause had been collecting the recordings for 45 years. Encountering the work at the Biennale of Sydney two years ago, I struggled at first with sensory overload. The beams of light that encircle the black space. The chorus of croaks and growls and hums that escalate to a heightened pitch. When I learnt that 70 per cent of these species no longer existed, the work started to feel elegiac and, suddenly, I could enter it.

“Not only does Bernie understand that sound comes from animals, but music emerges from all sorts of [sources],” says Clark, who has also collaborated with the neurobiologist Mark Changizi and the choreographer Benjamin Millepied. “A sound passing through reeds can be activated by a person over time into music. There are so many perspectives of where music has evolved from but also what sound can tell us.” He stops for a moment to reflect on this. “If you use your eyes, you could look at a habitat and it might look fine.”

To make Silent Symphony, a collaboration with Icelandic–Australian composer Ben Frost that was originally commissioned for Dark Mofo, Clark turned to the cosmos. He tells me Pythagoras, the Greek philosopher best known for his theorems, once believed the universe produced rhythms that were inaudible, to which mortals weren’t attuned.

“It isn’t true – [the universe] is very chaotic,” says Clark, who will show the work in a circular formation at Melbourne Town Hall. “But through NASA, we found this group of dwarf planets that oscillate and orbit around the sun and create these really interesting harmonic patterns. It’s the kind of work that pulls you in, seduces you into this safe, meditative space. But at times it becomes frightening.”

For Clark, Silent Symphony reimagines celestial patterns as sculpture. Like all his work, though, it aims to grapple with the forces that jockey for our attention by drawing us beyond the realm of the perceptible.

“I have neurodivergent challenges and have a personal desire to create spaces in which you are not distracted by anything but the present,” he smiles. “In the back of my mind, if people are willing to stay in a space and contemplate what’s going on, to me that’s the sign of a successful artwork.”

This article was first published in the print edition of The Saturday Paper on

August 3, 2024 as “Kinetic curiosity”.

For almost a decade, The Saturday Paper has published Australia’s leading writers and thinkers.

We have pursued stories that are ignored elsewhere, covering them with sensitivity and depth.

We have done this on refugee policy, on government integrity, on robo-debt, on aged care,

on climate change, on the pandemic.

All our journalism is fiercely independent. It relies on the support of readers.

By subscribing to The Saturday Paper, you are ensuring that we can continue to produce essential,

issue-defining coverage, to dig out stories that take time, to doggedly hold to account

politicians and the political class.

There are very few titles that have the freedom and the space to produce journalism like this.

In a country with a concentration of media ownership unlike anything else in the world,

it is vitally important. Your subscription helps make it possible.