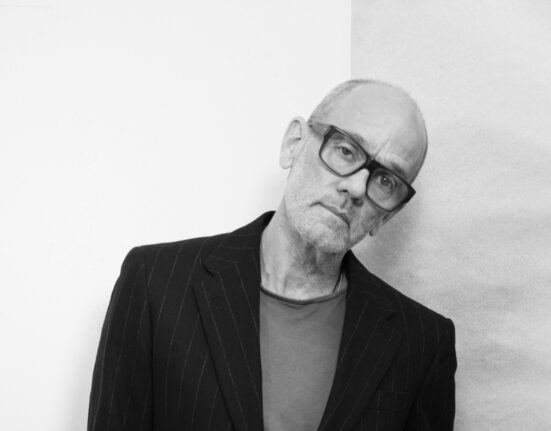

Visual artist and curator Camilo Pachón discusses using art as a tool to increase connection between people, erase borders, and fight big problems.

What does your creative practice consist of?

I am a visual artist and I have a social art practice. I’m really interested in working with communities from a decolonial perspective.

Have you always focused on communal work in your artistic practice?

I studied art and I always focused on working at the intersection of science and spirituality as I found art a bridge between those worlds, and a way to see the world. I finished my art degree and had a burn out after an intense full-time money job that was meaningless to me. I left Colombia for some months to recover and I eventually discovered that a very important part of my personal spirituality was mediated through working with communities, and feeling part of something.

I moved back to Colombia, and I decided to only do projects related to or with communities, to take collective approaches in cultural environments.

I started regarding the collective as a tool, as a powerful way to approach societal problems.

How do you find the people you want to work with? How do you approach them? What does you social art practice encompass?

It depends. Usually communities invite me to work with them. Sometimes I help them do certain things or I participate myself. The most important thing is that everything starts from a human relationship. I meet new people, I connect with them on different levels, there is a human interaction occurring. I want to support the communities and work for and with them.

3576 fragments of sea, From the series ‘The Spirits Of San Pancho.’ 100×65 cm. Giclée print on cotton paper. Nayarit, México, 2019

You need to develop a connection and a way to work together?

Yes and it’s important to ask certain questions: How does the community work? How does this community differ from others I have worked with? What are their values? What do they want to share? What do they want to create? And then, using art as a tool, we collaborate to transform and address challenges.

So, once you’ve somehow connected with a community do you really ask,”Okay, I’m here…I want to help. What are current problems or how can I help you?” Is you offering help really that explicit?

In some cases it is. For example, I’ve been working with a Colombian intercultural collective of young indigenous people, that work in communications. The head of the Inga nation invited me and one of my artistic partners to support them in creating a media collective. So I asked: “Why is it important for you to create a media collective? What perception do you have of a media collective?” And he showed us the importance of communication between different indigenous communities so that young people from diverse indigenous nations can gather together, create a unifying force, against the big problems they all face. For me, it was like, “Wow, this is one of the most powerful ideas and we should start thinking like this all over the world.” Let’s forget about borders, let’s forget about differences, and let’s concentrate on our similarities, and then let’s fight against problems together.

And it’s also important to let these young people know that they have the possibility to connect with others as a way of empowering them.

I’m grateful to keep learning from the communities I work with.

First Filming Team: Elkin, Edith, Norelly, Leimer, Rubiela, and Luis, youths from the Inga, Awá, and Siona nations.

In that example, what project did you end up doing with them?

During that time, I was working with Ambulante, a free documentary film festival that we created with a group of close friends in Colombia. There, I was the director of AMA, a nomadic filmmaking training program in documentary films for underserved communities in remote and rural areas of Colombia. With it, we went to different communities to share tools with young people and amplify the voices of the community. A lot of times people will come in from the outside to tell others how those communities live. We want to empower the community members by giving them the knowledge and tools to be able to talk about what is important to them.

Making films is quite a pyramidal system—many people are working for the director—so we flipped the pyramid by putting the community on top and me and my team on the bottom. Everyone is working for the community including the community itself.

So in this case, we went to live for a month in an indigenous resguardo (protected territory/collective territory) with teenagers from six different communities. We accompanied and advised them in the search and creation of their stories, filming and editing, and then screened the films in their community, we created a cinema in the middle of nowhere. I think it’s also powerful for the community to see their own values on a screen. Finally, we screen the films throughout Colombia.

In Colombia I’ve often witnessed how culture has the power to stop problematic situations. I truly believe that art practices can lead to transformation. Art is a tool to increase connection between people, to erase borders, to fight against big problems.

Filming of the short documentary IACHACHIDUR by The Biocultural Peace Communications Collective Ñambi Rimai.

And now that you live in Germany, do you still continue working with local communities?

I wasn’t interested in exhibiting my art for many years as my focus was on community work. Many people from the art scene, don’t even know what I’m doing, and what I did in the past. And now that I’m living between Germany and Colombia I’m trying to take a step back, reflect and think: How can approach my art practice? How can I share the things I learned in my art practice with others? I want to consider how the processes I went through can be helpful in a new context and how they can evolve.

You were so busy working with communities that you didn’t even have time to create a website or do exhibitions?

Something like that. I was jumping from one project to the next. For years I spent six months of the year living outside of my home making documentaries and developing projects for communities all over Colombia. These continuous sessions with indigenous, Afro-Colombian, and farming communities was like doing a Ph.D.—I truly believe in this way of learning.

And now that you’re in Germany you will come up with ways to distribute and share the knowledge gained from you social art practice?

Yes. And just as a side note, in Colombia we don’t have the term “social art practice.” It’s just a cultural practice for us.

By being part of discussions in Germany I realize a lot of the tools communities created together are not common in the art field yet, in my experience, I feel the art field is looking for the kind of support these tools are able to provide.

Community premiere in the Sibundoy Valley of the films IACHACHIDUR and Norelly, produced by the Indigenous Youth Collective.

It’s really impressive for me to see how advanced a small country like Colombia is in these processes. How we deal with really big problems through softness and human processes within our culture. We are always immersed in a violent context so we already know that violence is not the answer. We create a force through culture but not a violent force.

Colombians are always thinking in terms of community. It’s our life. Being in community is normal for us. To me it’s been incredible to experience the more fucked up a country is, the more it will come up with powerful solutions. And I believe these solutions can also be helpful in the global context.

And now that you left Colombia…

I need a moment now to consider myself, to reflect, to understand what I have experienced. I did an artist residency two years ago and when it ended they asked me to stay and work for them so now I live in an ever-changing community of artist, writers and composers with a lot of space to work and a lot of quiet as the residency is in a rural area.

Masks and carnival are important for you as an artist. Can get into that?

When I began connecting with spiritualism and was starting to think about how I can manage my spirituality, I went to a Colombian carnival for the first time and found that art and spirituality are being connected there. There, I understood the idea of collectively transforming yourself, becoming a different type of being or spirit. I started researching masks and the potential of that technology: How by covering your face, your identity you can create a new spectrum of your spirit within a collective perception.

This research connects me to different practices all around the world, practices that believe in being part of the same ecosystem, that share spiritual values and connect nature to their practices, who create rituals to connect communities so they can celebrate themselves yearly.

That’s a really fascinating way to look at masks.

I think that this kind of antique technology, able to cover our being and to remove ourselves from ourselves, gives us the opportunity to rethink the world, to create new communities, and new practices. I started working with those practices all over the world, and it’s unbelievable, because even here in Germany, in Bavaria, there are still ancient practices involving masks. On the surface I found either no spirituality in Germany or a very Silicone Valley type of spirituality. But then you go to Oberdorf, Bavaria where the community dresses up as monsters in animal skins and kick up a ruckus to fight off bad spirits. It’s a pagan tradition in one of the most Catholic areas in Germany and the ritual looks like things I saw in Africa or South America.

And then you realize: even though I’m at the other end of the world, there are still practices connecting humans and communities to the spirit world, creating a deep relationship between humans and nature. So, what I thought wasn’t present in Germany is actual there.

I strongly believe, that if we cannot remember and redefine ways to connect with nature, we cannot protect ourselves from the impeding crisis. If we can start thinking of nature not as a resource, but as another spirit that shares this life with us like our ancestors, then we would be able to realize that we are not the center of the system — but a small part of it.

Camilo Pachón Recommends:

The collective power is within you.

Explore the life of Taita Paulino the oldest shaman of the Inga Nation portrayed in IACHACHIDUR, the first documentary film by the indigenous youth of the Ñambi Rimai Collective.

Remember, you have multiple dimensions, and you can create significant changes with a slight shift in the spectrum of your reality. Explore some of them with us at Carnaval Digital

Move your body with Cobra (House of Tupamaras) Dj Set

Cera Perdida by Frente Cumbiero.

The Walking Mountain Collective performance on the physical and spiritual impacts of increased Colombian coal imports into Germany. Cologne, Germany, 2023.