Visual artist Steve Locke discusses public art, the difference between memory and history, and how Black history is sometimes white history.

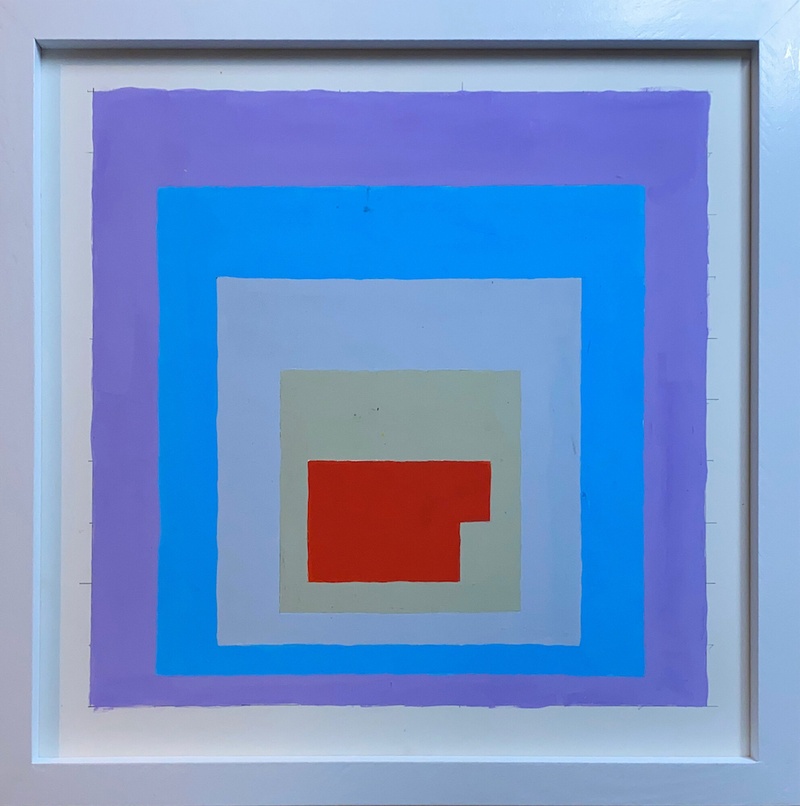

I want to start with the painter and educator Josef Albers. Albers is known for Homage to the Square, which he did from 1950 until his passing in 1976. For more than three years, you’ve done your own version, titled Homage to the Auction Block. Why him, and why that series?

Well, everyone who studied art has had to deal with Albers in some way. I had a rather traditional art education where I did the color studies course that Albers wrote. It was drilled into my head very early on. I think it is for a lot of people. “This is how you make this color do this.” “This is how you make this color do that.” It was a practical thing. I never really thought of it as a site of expression.

It was an exercise to learn something.

Right. When I was working on a project for the city of Boston, I was doing a lot of drawings of an auction block. I was trying to draw it in plan. But the auction block is actually an interesting form for a painting. I made a couple of rectangular paintings of it, and when I made one on a square support, it immediately made the connection to me with Albers. It’s a connection between modernism and enslavement. That’s something I can talk about. I can talk about my love for Albers—which is so crucial in my development—and I can also talk about the thing that I’m interested in—which is how enslavement really created the modern world.

How are you selecting the palettes? Are you recreating color combos that Albers did?

Oh, no. His interests are very different than mine when he’s selecting color. He was painting in oil, which limits what he could do, and I’m using gauche. There are also more colors available to me. I’m sure, you know, if he went to a store today and saw all the acrylic paint, he would lose his mind. We have all these colors that didn’t exist when he was alive.

We’re both conceptual artists trying to get the colors to advance and recede, but ideas about recession and advancement are linked to ideas about enslavement. I’m trying to see when the block comes forward, when it goes back, when it feels inevitable. I want to make color move in specific ways to generate a particular kind of conceptual feeling alongside a visual feeling. Albers laid the groundwork for me to think about these things in a more particular way.

Homage to the Auction Block (acrylic gouache on panel), 2019 and ongoing.

You also state on your website that this exploration of Albers is “a catalyst and an affirmation.” What is it catalyzing? What is it affirming?

Well, there’s a weird thing right now in the art world where if you’re in dialogue with another artist, you must be critiquing them. It’s assumed you’re being negative about them, or you’re undoing the damage that they’ve done. I’m not interested in any of that with regard to Albers. I have a great affection for him. I think my work affirms what he was setting out to understand—the relativity of color.

I think about the relativity of color as a Black person walking through a white world. Albers also thought about difference. He fled Germany because people were going to murder his wife. He was a refugee. When he came to this country, he didn’t speak any English. And eventually he goes on to integrate Black Mountain College. So he’s not like some random white guy in the art world, you know what I mean? He’s not some dead white male as if he’s all bad or whatever. He left everything to save his wife’s life. So I have a tremendous amount of respect for him and for Annie and for what they went through and for what they did at Black Mountain College. I mean, they brought Jacob Lawrence to Black Mountain College.

You also make work in a public art context, like Love Letter to a Library or Three Deliberate Grays for Freddie. I’m wondering if you would ever consider doing one of these homage to the auction blocks at that scale and at that sort of public space.

I would be open to it. The hard part about it is that most of my public art is fabricated, not painted. Somebody else fabricated the banners from Three Deliberate Grays or the flags from Love Letter to a Library. I designed them and someone fabricated them.

Because Homage to the Auction Block is painting, I’d have to ask what would happen if someone else painted it. How would that change the meaning of the work? What do I think about doing things at that scale with this particular body of work? Am I interested in the labor and the authorship? And color is so different when it’s outside than it is when it’s indoors or in my studio.

Three Deliberate Grays was weird because when we did it originally, the colors looked terrible because the fabric they were printed on was translucent. We were installing it on the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, which has that sort of copper green patina. The green was coming through in the sunshine and corrupting the colors we had picked. I had to adjust the colors so that they would look the way I wanted them to look, even though the colors on the work were different from the ones that I used to make the piece.

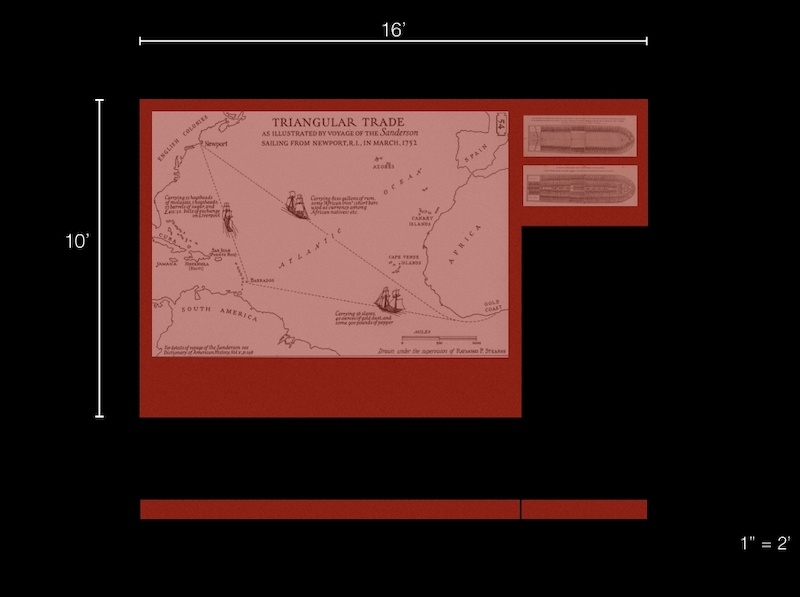

Artist’s rendering of Auction Block Memorial at Faneuil Hall: A Site Dedicated to Those Enslaved Africans and African-Americans Whose Kidnapping and Sale Here Took Place and Whose Labor and Trafficking Through the Triangular Trade Financed the Building of Faneuil Hall (bronze with heating elements, 10 x 16 feet), 2018.

Do you consider Three Deliberate Grays or Love Letter to a Library collaborations with other people?

The executions were definitely collaborative. But the ideas were not. I’m not a social practice artist. I’m not in conversation with communities in that way for that kind of work. I’m not opposed to having those conversations, but with those particular works, they weren’t. No one contributed to the idea.

Auction Block Memorial is also a favorite of mine—your proposed memorial in the shape of an auction block in Boston directly in front of Faneuil Hall, heated to the temperature of a human body and flush with the ground. That hall historically functioned as a site where white colonists sold enslaved Africans. While the project’s not advancing at that particular site, I’m wondering if you have other cities or locations reaching out to put the auction block elsewhere.

I had a wonderful trip to Charleston, South Carolina last year with the folks down there and met with the mayor and talked with a bunch of people about it. South Carolina has a very strange and difficult history they’re wrestling with. They just took down a huge statue of Robert E. Lee on a giant pole overlooking the entire city. And that was a huge fight to get that thing taken down. That statue is a block from where the Emmanuel Nine were murdered.

South Carolina has seen the limits of people’s lives. And so they were really open to the conversation. There are white people in South Carolina now, not just Black people, who are saying we have to deal with this. And some say it’s just a Confederate flag, so it’s not a big deal. Some still say it’s just a statue of Robert E. Lee. It’s not a big deal. Until someone embracing those symbols murders nine people. All of a sudden these people went from “It’s no big deal” to “It’s a big deal. We have to take that thing down.”

I never had so much faith in race relations until I saw white people in the streets after George Floyd was murdered. White people were in the streets. I thought, “Oh see, y’all know it’s about you now. Now you see yourselves and somebody else now.”

Hearing white people in South Carolina honestly discuss their own relationship to slavery gave me a lot of hope. People admitting “This is what my father did,” or “This is what my parents did. This is who they were. We have to fix this.” And it didn’t feel needy, as if I was supposed to fix it for them.

It reminds me of that saying that a lot of Black history is actually white history.

Oh yeah. People really think it’s about Black people, when it’s like, “No, honey no, this is about you.” People still get so upset about teaching the history of enslavement because they think all white people are to blame. And I say to them, “Why do you assume that you would’ve been on the side of the enslavement? That’s the team you think you’re on? There were white abolitionists too, you know.” If I were a white person, James Reeb would be my hero, or Michael Henry Schwerner and Andrew Goodman. I’d want to be like all those white freedom riders.

In my Midwest public school system, we didn’t study white freedom riders. I don’t even recognize the names of those people you just said.

That’s a goddamn shame. I had pictures of Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner in my house when I was a kid. Those were white people who died for human freedom, murdered by the Klan.

Love Letter to a Library (flag), 2018.

And probably there are other white people like me who don’t have examples of whites on the side of abolition and progress. Robert E. Lee, Jefferson—they’re the only ones we see.

That’s what whiteness is: the idea that those are the only people you get to be. You can either be human, or you could be white—and some people just choose to be white. It’s pretty shitty. There have been white people of honor who fought for human freedom. Some of them paid for it with their lives. It makes me sad that white people don’t know them, but I do.

How do you think about the different audiences between a work that’s outdoors and a work that’s indoors?

I know what’s going to happen when people look at the work either way. But with public art, I have to know what will happen when I introduce a form into public space. I have to articulate what’s going to happen before the thing is built. I could tell you everything that was going to happen if we had installed Auction Block Memorial at Faneuil Hall. I knew the space. I knew the object. I learned about foot traffic. I learned about the tourists. I learned about all that stuff before I even proposed it.

With painting, sometimes you don’t know what’s going to happen. Sometimes you don’t know what’s going to happen if you put two guys in a painting and they’re looking at each other. You don’t know if it’s going to look violent, or if it’s going to look like a come on, or if it’s going to look like indifference. You make the painting to sort of figure those things out, right?

Part of me thinks that’s because public art has stakeholders, approvals, and a bureaucracy artists have to pitch. They have to prove that their work will have an intended effect.

That’s a big part of it. You end up educating them on what it’s like to have an aesthetic engagement with something. People confuse it with being entertained, like watching fireworks. People think that’s the correct response you’re supposed to have from public art. We’re trying to do something deeper, something more than that. And that’s the thing that I think a lot of people have a hard time with because they don’t understand that art can be something other than decoration.

The majority of the projects we’ve been discussing use archival, public, or found imagery to start. You then transform that research and open space to discuss how we remember history. How important is that practice to you—the act of starting the work’s journey at a point in history?

I have an acute memory of a whole group of people just being erased, literally erased. And so I knew that people say that objects don’t matter and stuff like that. And I just think the objects are all that’s left of some of these people. And so becoming an artist in the teeth of that epidemic, really was a lot about witnessing and saying we were here and this happened. It’s in the DNA of my work—to be a living witness.

I also don’t want to just tell the part that reflects good on me or reflects good on people. I just want to tell the whole story. The whole story is more interesting than a lie.

What’s the difference between history and memory?

History is empirical. History actually happened. Memory is just what you remember. Sometimes you remember, and sometimes you don’t, because they’re not accessible to you or you don’t want to remember them. History is not like that. History happened whether you want to believe it or not. And that’s the hard thing. That’s why I don’t deal with memory, I deal with history.

When do you think the two get mixed up for one another?

When people try to make history about their feelings. I’m not someone who is very interested in people’s feelings. I’m not interested in emotionalism because I think it’s incredibly manipulative. Like people were saying to me with The Auction Block. Some people argued I was claiming to speak for the enslaved. I never said I was doing that, so that’s on you.

When people start to conflate history with their emotions, you end up with really bad gestures in public space because we’d be making art for people’s feelings. I got an email the other day from someone who asked me about designing a COVID Memorial. I wrote back to them and said, “People are still dying. You can’t be building a memorial now. You build a memorial when people start to forget.” The idea that somehow COVID is over and now we’re going to memorialize it is kind of crazy.

Also, who’s the memorial for? If we’re dealing with memory, it’s for the people who remember. But if we’re dealing with history, we’re dealing with the people who don’t know. I’m not interested. Everybody already gets a memorial: it’s called a headstone.

And those headstones are already public gestures.

Right. We get angry when people use memory to build Confederate monuments because that has nothing to do with history. Those monuments are about memory and oppression. They’re about uplifting a certain group of people’s memory of what happened and why it happened at the expense of other people.

A memorial is supposed to encourage you to remember something that actually happened. That’s the difference between something that is successful outside of its time and something that is only successful to the people who know how to read it. Take the Emancipation Memorial, built by Thomas Ball in 1876. The original is in Washington, D.C. it’s also called the Freedmans Memorial, because it’s the first monument paid for by free Black people. They paid for it to honor Lincoln, who had been assassinated. There’s a copy of it in Boston.

Some people said it was offensive and showed Black people in a subservient position on their knees in front of Lincoln. But what does that say about you? It says you see an image of a man standing on his feet and you think he’s kneeling. That’s not about the statue. That’s about you. The codes and the systems of allegory or symbolism that were available to someone in the 1800s aren’t available to us now. And people are too lazy to try to understand that. They say, “It makes me feel like he’s subservient, so that’s a bad image and it has to come down.”

Suddenly, things have to be what they represent today, and not in the past. So a statue of Sojourner Truth has to look like Sojourner Truth. It can’t be a monument to her. It has to be an effigy of her.

Three Deliberate Grays for Freddie (A Memorial for Freddie Gray) (façade installation), 2018-2019.

I ran into a sculpture called Civic Virtue by Frederick MacMonnies at the Green-Wood Cemetery. It’s of a muscular man who represents Virtue, standing on top of two siren-like women who represent Vice. It was originally installed at City Hall, then moved to Queens, then landed in the cemetery because concerted feminist groups successfully argued to the city that the statue was mysoginist. What do you think about this example?

The art of the past is understood with conventions of the present, thereby misunderstanding the art of the past. The people are judging that sculpture from the past by today’s standards. And there’s something lost there. In the 1800s we weren’t thinking about men and women in statues as the literal people sitting next to you. They were allegorical for values. Do you know any guys who walk around naked with a sword? We’re applying the rules of our lives to an object that’s a moral lesson.

We couldn’t make that sculpture now. People would still think it’s sexist—and maybe it is. Today we know it’s sexist to think of all women as evil. But there’s a demand today that all art be affirmative and good and positive. And I say no. Sometimes we make images that are warnings—like how virtue is under attack by vice. That goes back to St. Anthony being seduced by female demons who tried to seduce him into having sex, so that allegory has been with us for a long time.

I’m also sure people probably had problems with it when it was made for different reasons, like the man being naked or carrying a sword instead of a gun. MacMonnies got slammed for a lot of his work. His work was even banned in Boston, like his statue of Bacchante and Infant Faun—a woman dancing with the baby, a “sexy” baby with grapes. People got so upset with that statue that it had to be hidden in a library for years.

I just tell people that when we talk about art, we’re talking about ourselves. If you think that’s sexist, then okay, great. Can we move on? Just don’t go to Green-Wood. If you don’t like it, why are you forcing yourself to experience it? If you don’t like it, just don’t go.

So then what’s the difference between the MacMonnies sculpture that’s perceived as sexist, where your answer is keep it up but don’t go, versus the Robert E. Lee sculpture and needing that to be taken down?

The difference is that the MacMonnies piece wasn’t put up specifically to intimidate women. The Lee statue was put up to intimidate Black people, and put Black people in their place. Robert E. Lee was not a neutral allegorical figure.

But we got to a point where the majority decided that it should come down. That’s the same thing that happened with the statue in Green-Wood.

And who the fuck am I to deside? I’m just one guy in New York. I didn’t think the Teddy Roosevelt statue in New York was a problem, because I understand what allegory is. I didn’t look at that statue of a Black man in an allegorical position and think that that had something to do with me. I don’t look at statues to affirm me. That’s not the purpose of art.

When I hear people say we need more representation of this person in the media, I think, “Well, maybe we do.” But I don’t know why people can’t find themselves in other people’s stories. That’s always been my problem with white people. Like, everyone is supposed to be into Star Wars. Everyone’s supposed to love Star Wars. But the minute they start putting Black people in Star Wars, white people get upset.

I saw myself in Han Solo. I wanted to be Han Solo, I thought he was cool. I didn’t think Han Solo was white, I thought he was from another planet. I didn’t think he was from Earth. The movie takes place in space. I identify with Han Solo, I was fine with that. But the minute they put like a Black woman, somewhere in Star Wars, people get upset. Like, why are you mad? Can you not identify with her because she’s Black? When I read The Great Gatsby, I imagine everybody in The Great Gatsby is Black. You can do whatever you want in a made up story. White people think the world is organized around their self-representation.

How does art that looks at our violent past build empathy?

The only thing I can really do as an artist is make you pay attention. If I can make you pay attention, I believe I can change your mind. I really do. Otherwise I wouldn’t be doing this job.

It’s like our superpower, if we have one. Artists can make people pay attention. And I’m just trying to get you to pay attention to the person sitting next to you, or the way your eyes work, or where you’re standing. Because I think if we really, really pay attention, we might survive. We might make it.