By Peter Walsh and Kathleen Stone

Was John Singer Sargent just a talented flatterer of his wealthy patrons or was there more to him?

John Singer Sargent, Nonchaloir, or Repose (1911). Photo: National Gallery of Art

Two Arts Fuse critics were interested in reviewing the same show — Fashioned by Sargent, currently at the Museum of the Fine Arts through January 15, 2024. In the past, the magazine has published more than one review of the same event, an experiment meant to relive the era when there were a number of newspapers in every large city and they all supported critics, leading to varied points of view on every concert, play, performance, or art exhibition.

This time we are trying something else, more like a conversation. We will post more than once on the Sargent show. The first installment features Kathleen Stone’s brief initial thoughts about the show, followed by a reaction by Peter Walsh before he has seen the exhibition. The post below features Walsh’s incisive impressions of the exhibition and a response by Kathleen.

Readers, please feel free to add your voices to the dialogue and our critics will respond to you as well. The magazine has already had a provocative commentary on Fashioned by Sargent from critic and artist Mary Sherman.

— Editor Bill Marx

Hi Kathleen,

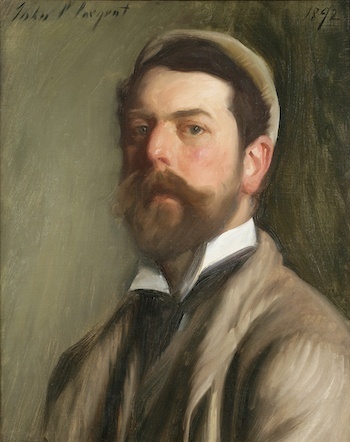

John Singer Sargent, Self-Portrait, 1892. Photo: National Academy Museum, New York

So I have finally, actually seen Fashioned by Sargent and am ready to write my second post in our collaborative review.

This is a very interesting, thought-provoking show of major works by one of the most important artists in Western portraiture. There is a lot — too much — to write about.

I’d like to start by going back to a couple of points you made in your initial post (you had already seen the show). Yes, this is an important exhibition: 50 works by a great virtuoso of the brush, including several of his most famous portraits. Anyone with even a passing interest in Sargent or portraiture should definitely take this as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and go see it. This is not to say I didn’t have many reservations about the MFA’s framing and presentation of the topic. Much more about this in a bit.

I have always had a soft spot for artists with brilliant drafting skills: the ability vividly to evoke the real world in brushwork or line while also displaying a great command of art as art rather than simple reproduction. Michelangelo, Bronzino, the Carracci brothers, Guido Reni, Rembrandt, Ingres, Degas, Picasso — these are all artists who delighted in showing off their great gifts for rendering life in line. Sargent is part of the tradition. The revival of interest in Sargent that began at the end of the last century must owe a lot, I think, to this sheer virtuosity. It is easy to delight in his rendering of folded fabric, beautiful faces, rich costumes, and the human body, clothed or nude, in a striking pose.

But was Sargent just a talented flatterer of his wealthy patrons or was there more to him?

The second point I would like to take up is your question “whether the artist’s direction of clothing choices, and how he painted the garments, is a sufficiently compelling inquiry to anchor an exhibit.” My conclusion is that, yes, it is, but that the MFA probably hasn’t managed to pull it off, which leads me to another question you asked: “whether the exhibit fully explores the question.”

Sargent was interested in clothes and dressing, but not particularly in high fashion. As a portraitist, he was interested in clothing primarily as a painterly effect. When he couldn’t find the right effects in a client’s ample and highly fashionable wardrobe, he could resort to an ill-fitting, borrowed gown or even a flourished length of untailored cloth. Or he just made things up, whole cloth as it were, on the canvas.

So the name of the show, Fashioned by Sargent, despite its clever punning, gets things off on the wrong foot. Besides falsely connecting Sargent to the glamorous world of fashion and designers, the title vaguely suggests that he was some kind of old school version of the contemporary Hollywood profession of “fashion consultant” — people whom actors and other celebrities pay to tell them what to wear to high-profile red carpet events like the Oscars, with an emphasis on status-conferring designer labels. This is not what Sargent was up to at all. He didn’t particularly care who made the dress; in fact, he often passed up the glittering designer evening gown for something much more domestic and ordinary. He did commission, for one portrait on view, a “fancy dress” gown from the premier Paris dressmaker, House of Worth. Worth considered his creations to be works of art, with “Delacroix’s sense of color.” The Worth gowns in the show tend to reinforce his claims. He is an unexpected sidebar star of the show.

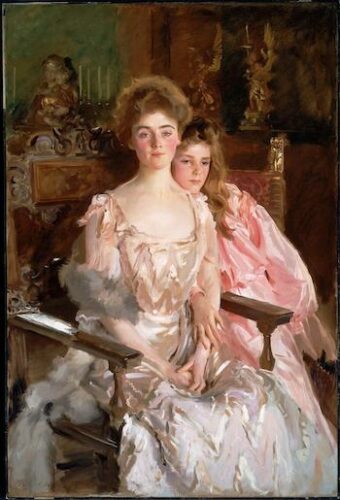

John Singer Sargent, Mrs. Fiske Warren (Gretchen Osgood) and Her Daughter Rachel, 1903. Photo: MFA Boston

The problem is that the exhibition ultimately fails to come up with an encompassing theory of Sargent’s approach to dressing his sitters. Part of the difficulty is just a lack of hard facts. Like most artists, Sargent made no formal record of his sessions with his clients. So Fashioned by Sargent is forced to rely on snippets gleaned from letters and “family lore,” which is not highly reliable. The premise suggests that the physical fashions on view, posed in glass cases near the portraits, are the ones Sargent painted. But this is only sometimes the case. When the historic model is not available, the curators make substitutions, sometimes using other dresses from the sitter’s wardrobe that are not anything like what Sargent would have chosen himself. In other cases only a fragment survives, or else the dress has been so altered over time that it “is and isn’t” the garment in the painting.

The label copy describes the sitters’ costumes formally, using language similar to that of a society reporter; there are extensive quotes from newspaper accounts of the time. Sargent, the labels conclude, favored black and white, the latter apparently because of the color variations and shapes he could render in paint— an interesting observation, but not a particularly compelling one. A more intriguing question, if one more difficult to answer, would have been why the furious controversies over a handful of Sargent’s paintings always seem to have been inspired by his sitters’ clothes — Madame X in particular, but also Dr. Pozzi at Home and other works — rather than the lack of them, as had been the case a few years earlier with Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia.

Fashioned by Sargent is confusing in other ways as well. The labels wander off into side issues, including gender roles, colonialism, cultural appropriation, and other trending contemporary topics without ever really exploring them. They frequently describe Sargent’s clients as “friends” and “close friends.” The terms suggest Sargent lived beside his clients on comfortable terms, cocooned in a world of affluence and high privilege. This glosses over a host of complicating factors in late 19th-century social relations.

Socially, who was Sargent to his sitters? People often assume that Sargent’s family, like those of his sitters, was wealthy. It was not. Sargent’s father’s family had had money but lost it; moreover, the elder Sargent had given up his career in medicine when his family took up a life as perpetual tourists in Europe. Mrs. Sargent had inherited enough — just — to support the family as long as they stayed in Europe, where the cost of living was lower. There the Sargent’s stayed in hotels and furnished apartments, moving to a different city every few months, owning little more than their clothes.

The family’s constant moves made it all but impossible for the young John Singer Sargent to attend local schools. His parents were reluctant to send him to a boarding school, perhaps because of the added expense. They also resisted art training until John’s obvious talent and devotion made them relent. Though he spoke four languages and knew the art history of Europe from firsthand encounters in museums, Sargent’s only formal education began when he entered, at age 18, the Ecole de Beaux Arts in Paris, the world’s most prestigious art school.

John Singer Sargent’s Madame Ramon Subercaseaux, 1880. Photo: Wiki Common

All this meant that, for all his continental polish and talent, Sargent’s socioeconomic status was far below that of most of his society patrons, which included the de Rothchilds and the Sassoons, two of the richest families in the history of the planet. As a portrait painter, he was always “in trade,” always alert to the next connection to the next client rich enough to pay his increasingly high fees. It was, at least at first, a precarious life; he had nothing else to fall back on. Sargent was prolific because he had to be. Relations with sitters could be cordial and even warm, but they were essentially business transactions, much like the relation of a stockbroker to his clients.

Given his situation, what did Sargent make of his talents? Broadly speaking, he made three kinds of portraits. There were the formal society commissions, which are the focus of the MFA’s exhibition. For these Sargent received jaw-dropping fees. There are the “spec portraits” like Madame X, that were not commissions. Sargent made them from acquaintances or friends, sometimes from models he encountered on his travels. These were intended as eye-catching compositions he hoped would make a splash at the Paris Salon and other high-profile exhibitions; this notoriety would bring him more sales and commissions (Madame X was a serious miscalculation). Finally there were his portraits of close friends and family that he seemed to make primarily for his own enjoyment.

The division is partly expressed, if a bit clumsily, in the exhibition’s design. The show begins and ends with large, brightly lit galleries painted in pastel shades. In between there is a series of long, narrow spaces like corridors. The walls are painted dark shades, as if to evince the moody atmosphere of the Aesthetic Movement interiors of the era. Some are covered in tendril-dense William Morris wallpapers. The day I visited, though, the galleries were choked with holiday visitors and the winding spaces created bottlenecks that forced you to move fairly close to the paintings to see them. Unfortunately, the dramatic lighting created hot spots at that distance, often obliterating the faces.

These Gilded Age faces so rarely look relaxed. Only when the sitters and painter had a genuinely cordial relationship, as Sargent had with the Wertheimer family, do they seem to be happy with him watching them. The tension intimates the Faustian bargain they have made with the celebrated painter: not only to make them look handsome and impressive, but to make them immortal.

For all its current romanticization, the Gilded Age lasted barely a generation. It was a period of furious social climbing and competition, old money vs. new and new money vs. newer, lavish displays of wealth, gigantic, grotesquely overdecorated houses, and a complicated social code that could trip up the most confident socialite. Life, especially for women, was an endless round of generally tedious social obligations: interminable dinner parties with endless courses, teas, outings, social visits, nights at the opera, each requiring a different set of clothes. Edith Wharton brilliantly captured the ethos in her greatest novel, The Custom of the Country. On top of this, the unregulated capitalism of the 19th century was turbulent, with regular panics, bank runs, and crashes. Even the grandest Gilded Age fortune could smash like a falling chandelier.

John Singer Sargent, Portrait of Albert de Belleroche, 1882. (It is not the one in the show, though it is quite similar.) Photo: Wiki Common

How different are the portraits of Sargent’s true friends. Just before the last gallery hangs a sensuous portrait of Albert de Belleroche, an old friend from Sargent’s student days. Although the label doesn’t mention it, de Belleroche is one of several close male friends that have been described as Sargent’s lovers. The large sword in a sketch of de Belleroche reproduced on the label has even been described by a Sargent biographer as a “phallic symbol.”

The claims of homosexual affairs are all insinuations: there is not a scrap of hard evidence to support any of it. Yet they are reinforced by the large number of male nude studies Sargent made that began to be exhibited in the ’80s. These frankly sensuous images have been sensationally described as “secret.” A better word would be “private” or “unexhibited” or just “neglected.” After Sargent’s death in 1925, his sisters gave stacks of nude studio studies to art museums, including several institutions in Boston. Another set of male nudes decorated Sargent’s dining room in London. They are partly just extensions of the formal exercises of the Ecole de Beaux Arts’ curriculum, though their belated revelation formed an important role in the process of reevaluating Sargent’s achievements in the 1990s. After decades languishing in the dusty attic of the Gilded Age, Sargent suddenly seemed edgy and cool again.

Presumably because they are not wearing clothes, none of these male studies is included in the MFA show. But they, like the portraits in the last gallery, suggest the kind of career Sargent might have had if he had not been drawn into society portrait painting. (He did eventually give up society portraits, but by then the focus of his career had been set.) In these brightly lit images, mostly exterior scenes, family and friends — and another reputed lover, long-time model and valet Nicola d’Iverno — sprawl over the ground and each other in poses that completely ignore the social proprieties of the day. If Sargent had given himself to the subjects that gave him the most joy, what else might he have fashioned?

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

Hi Peter,

Your comments about the Sargent show make for a delightful read.

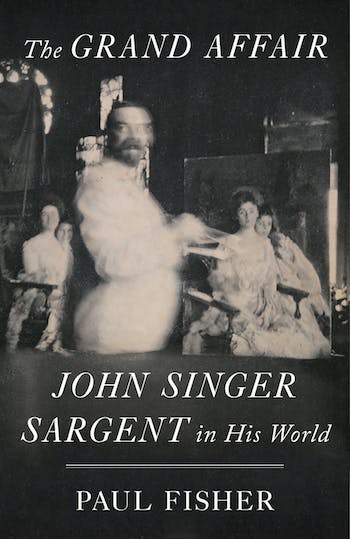

Thank you for reminding me of Sargent’s biographical background, familiar territory for you, judging from your review last year of Paul Fisher’s biography, The Grand Affair: John Singer Sargent in His World. Sargent’s life in Europe must have provided access to a broad range of clients, both European and American. That, together with his outstanding skill and social panache, made him the sought-after portraitist for scores of wealthy individuals and families on both sides of the Atlantic. He did not need to come from their world in order to succeed among them.

Thank you for reminding me of Sargent’s biographical background, familiar territory for you, judging from your review last year of Paul Fisher’s biography, The Grand Affair: John Singer Sargent in His World. Sargent’s life in Europe must have provided access to a broad range of clients, both European and American. That, together with his outstanding skill and social panache, made him the sought-after portraitist for scores of wealthy individuals and families on both sides of the Atlantic. He did not need to come from their world in order to succeed among them.

As I mentioned in the first round of our collaboration, I fantasized about which of Sargent’s subjects I would have liked to spend time with, maybe over coffee in a local café. This is my idiosyncratic response to the persons I perceived on canvas. Since then, I have done a little research and decided to enlarge the group of subjects I would invite for hypothetical coffee. Many of the women were highly educated and talented but most were unable or unwilling to abandon the role of society doyenne. Did they privately wish to spend their time in other ways?

This sort of musing brings a contemporary outlook to portraits painted more than a century ago. I hesitate to push it too far because, in my experience, “presentism” seldom enhances enjoyment of the art or deepens an understanding of the artist. The museum, too, flirts with “presentism.” As you mention, a number of wall labels refer to contemporary concerns, such as gender roles, colonialism, and cultural appropriation, without really exploring these issues. I found these references distracting and perfunctory, as though boxes had been checked.

I appreciate your taking up two of my questions — whether the exhibit is a response to a sufficiently hefty question, and whether that inquiry has been thoughtfully probed. I don’t have much to add, only one detail that underscores how little is known about how Sargent interacted with his clients about clothing. Sargent painted his friend Mrs. Joshua Montgomery Sears in a white gown, but we are told that she loved color. The label poses a rhetorical question – who decided what she wore? The insinuation is clear, but there is no way to know the answer.

Two final thoughts. The portrait of Edith, Lady Playfair, pulls together many interesting facets of Sargent’s portraiture. Edith grew up on Beacon Street in Boston and married a British man, an example of the cross-Atlantic society of the era. She wears what is described as an afternoon dress. Even with its boned bodice and huge bustle, an afternoon dress was more informal than evening wear. Sargent posed her next to a bunch of chrysanthemums that reflect the peach color of her bodice. But what I like best is the swath of peach-colored ribbon perched on top of the black bustle. The satin and velvet textures are so palpable and the colors are exquisite — reminders of Sargent’s immense talent. Last, I agree with you that the pictures in the final gallery are a highlight. Bright, informal, and often staged outdoors, their creative spark was infectious.

Kathleen Stone is the author of They Called Us Girls: Stories of Female Ambition from Suffrage to Mad Men, an exploration of the lives and careers of women who defied narrow, gender-based expectations in the mid-20th century.