“I painted part of the day today, while it was snowing continually: you would have laughed to see me entirely white, my beard covered in icy stalactites,” wrote Claude Monet in an 1895 letter to a friend in Paris.

Monet penned the note in Norway, in the dead of winter, where he’d traveled with the express intent of painting the stark but luminous landscapes of Bjornegaard and Sandvika. The trip was the culmination of a decades-long passion for Monet. The Impressionist artist avowed painting en plein air, delighting in capturing brumal landscapes in person. He painted over 140 winter scenes in his life—icy visions that experiment in luminously pale color palettes and celebrate the transformative effects of changing light against snow, fog, wind, and other wintry weather.

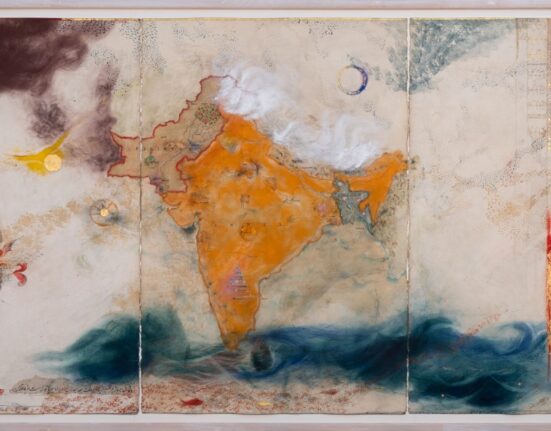

Claude Monet, A Cart on the Snowy Road at Honfleur (1865). Collection of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

His first snowscape, A Cart on the Snowy Road at Honfleur, was painted between 1865 and 1867. In 1868, Monet’s patron Louis Joachim Gaudibert secured a home for the artist—along with his girlfriend Camille Doncieux and their infant son—in the countryside near Etretat, France, where Monet would cultivate his passion for capturing subtle changes in the snow-covered landscapes around him.

His largest-ever winterscape The Magpie was painted there over the winter of 1868 and 1869. The rectangular composition pictures a country landscape blanketed in snow. A stone wall runs through the middle, dividing the horizon into foreground and background. No people can be seen and the landscape appears hushed in newly fallen snow. The witness to the scene is a black magpie that perches on a rickety wooden gate on the left-hand side. Amid the icy stillness, one can imagine the bird song of the magpie resounding through the forest.

Today, The Magpie is in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, where it is among the museum’s most popular paintings. As we head into the winter season, we decided to look a bit more closely at Monet’s famous winter scenes and located three facts that we hope offer new perspective.

1. Courbet’s Winter Scenes Inspired Monet—Though Monet Traded Realist Drama for Quiet Beauty

Gustave Courbet, Fox in Snow (1860). Collection of the Dallas Museum of Art.

Starting in the mid-1850s, the French painter Gustave Courbet began painting a series of landscapes of his home region of Franche-Comté blanketed in snow. Courbet described these paintings as studies of effet de neige— or the effects of snow—which explored the unique visual experiences of winter terrain. A Realist with a penchant for drama, Courbet often painted energetic hunting scenes. These innovative canvases proved influential to several artists who would ultimately pioneer Impressionism including Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro, and, of course, Monet.

Detail of The Magpie (1868–69) by Claude Monet.

But while Courbet’s scenes highlight the brutal drama of winter, Monet’s scenes such as The Magpie dwell in the subtleties of visual experience and are contemplative, even joyful. Historians note that Monet probably moved to Etretat in the hopes of recovering from a bout of depression. The change of scenery seems to have suited him. He wrote to his friend, the artist Frédéric Bazille, “I go into the countryside which is very beautiful here… I find [it] perhaps still more charming in winter than in summer and, naturally I work all the time.”

2. Monet’s The Magpie Cast a Critical Shadow

Detail of The Magpie (1868–69) by Claude Monet.

Notice the shadows cast by the stone wall and gate in The Magpie—Monet has painted these shadows in pale grayish blues. His snowy white, too, one notices is touched with blues. These were unconventional color choices at the time but were true to Monet’s careful perception. Monet’s visual acuity was informed by his tutelage under Eugène Boudin, a mentor to the artist, who was himself influenced by the Dutch painter Johan Barthold Jongkind. Jongkind is considered a forerunner to Impressionism and encouraged artists to paint directly from nature. In 1862 Monet met Jongkind in Normandy. Under the Dutch artist’s influence, Monet began to focus on optical color in place of local color—meaning color as it is perceived, rather than an object’s innate color. Monet later wrote, “Complementing the teaching I received from Boudin, Jongkind was from that moment my true master…It was he who completed the education of my eye.”

But the pale bluish shadows of The Magpie, though quite unobtrusive to viewers today, seemed unnatural and off-putting to contemporaneous eyes. “[The public] accustomed to the tarry sauces cooked up by the chefs of art schools and academies, was flabbergasted by this pale painting,” Felix Fénéon wrote of the painting’s public response to The Magpie. Today considered an idyllic winter scene, Monet’s painting was rejected by the 1869 Salon for its novel approach.

3. This White-on-White Winterscape May Have Been Inspired by Particularly Brutal Winters

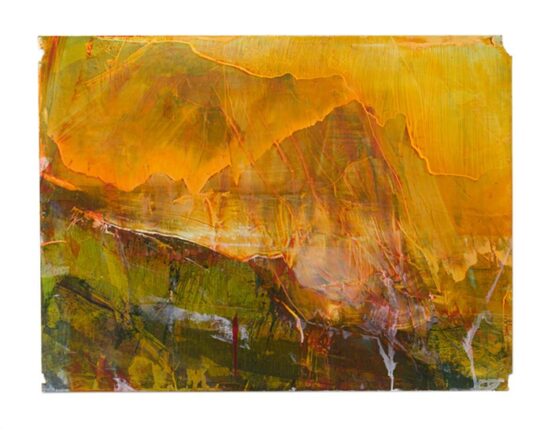

Claude Monet, Snow at Argenteuil (1874–1875). Collection of the National Gallery, London.

Today, art historians celebrate The Magpie for its chromatic virtuosity, restricted palette, and brushwork that hints at his burgeoning Impressionist style. “The blueness of the long shadows creates a delicate contrast with the creamy whites of the sky and landscape,” wrote art historian Michael Howard of the painting.

While visually innovative, Monet’s applications of white-on-white may been prompted by more everyday realities—a series of particularly harsh winters. The 1998 exhibition “Impressionists in Winter: Effets de Neige” at the Phillips Collection in Washington D.C.—curated by Eliza Rathbone—brought together the winter landscapes of 63 Impressionist artists (the exhibition later traveled to the Brooklyn Museum and the Yerba Buena Center for Arts in San Francisco). Art historians contributing to the exhibition scholarship posited beyond compositional considerations, a plethora of Impressionistic winter scenes were the result of several highly precipitous winters in the late 1860s and early 1870s.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.