Within the realm of comic books and sequential art, shared universes are popular vehicles for storytelling. Writers and artists come together and draw on common themes and ideas, incorporating their own work into a broader realm that exists beyond the sum of its parts. The Marvel and DC universes are the best known, but plenty of others exist, including an Alaska one.

Luk’ae Tse’Taas Comics (Fish Head Soup Comics) has been built in recent years by an assemblage of creators rooting their work in Indigenous cultures and northern themes, and peppering it with fantastical elements.

“We all had similar ideas of where this could go, what it meant to tell Alaskan comics or Alaskan Native comics or just comics for Alaskan kids in general,” artist Dimi Macheras said, recalling discussions he and other creators began having a few years ago, aimed at building a common vision.

He said they wanted to create an “open universe, a shared universe, where people can kind of come together and tell stories and we can keep each other in the loop.”

Macheras, who now lives in Seattle but spent much of his childhood near Chickaloon, is co-creator with Casey Silver of “Chickaloonies.” The manga-style comic follows the adventures of two boys, Sasquatch E. Moji and Mr. Yelly, in a tale inspired by the Ahtna Athabascan storytelling tradition Macheras grew up with. As with many comics that take place in shared universes, “Chickaloonies” works as a stand-alone production while belonging to a larger world of ideas.

“You do a single shot each time,” explained Nathan Shafer, who writes and illustrates the science fiction comic book “Wintermoot,” discussing how the various Luk’ae Tse’Taas creators contribute works to the shared universe. Each comic might have its own characters and plot, “but when you aggregate them altogether, there’s a bigger story that kind of flows through it. But you don’t need to see the whole story the whole time.”

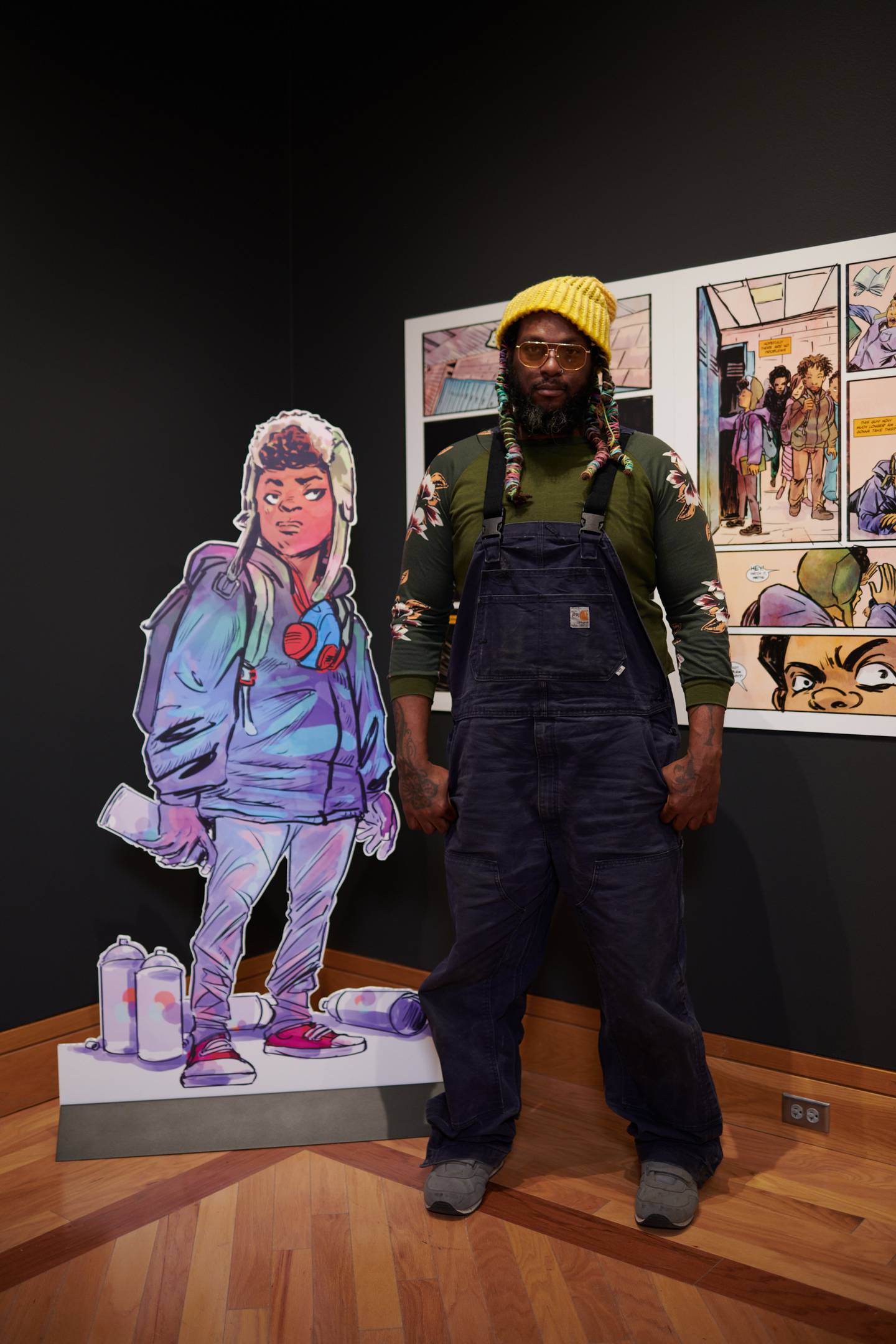

The stories that the contributors have been creating aren’t limited to comic books alone. Shafer works in new media. Macheras and Silver have brought a live action element to their story for presentation to children. And artist David Brame’s character Dusty Funk is depicted through mixed media.

“Whatever these different methodologies are,” Brame said of the collaboration, “the general idea is that everything is artistic, it’s creative, it’s about Alaska and it’s generally focused either around Indigenous futurism or Indigenous identity, on being an Alaskan, on Alaskan values and identity.”

Works by Macheras, Shafer, and Brame are presently on display at the Anchorage Museum, with an ongoing series of workshops and events planned around the exhibit. “We each have our own room that’s dedicated to our specific work,” Brame said. “And then we have a collective room that’s about storytelling and how to make comics, but from an interactive standpoint.”

The collaborative nature of Luk’ae Tse’Taas has its origins in an earlier project of Shafer’s. After learning of grandiose plans for constructing domed cities in Alaska that had once been floated in the 1960s, Shafer created an augmented reality world titled “Dirigibles of Denali,” which imagined that those domed cites had been built, and told stories that took place in and around them.

As the idea gained momentum, he launched his own production company, Shared Universe, and published several books, including a science fiction anthology that he invited an assortment of Alaska authors to contribute to.

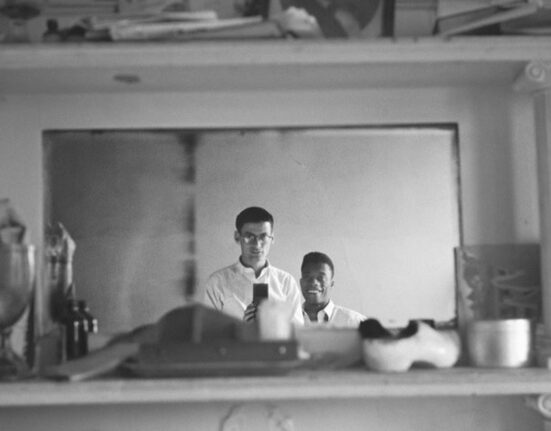

One of those authors was the late Richard Perry, a Yup’ik and Gwich’in writer and photographer who contributed the story “Denali City and the Wild Men.” Shafer, who had produced the first issue of “Wintermoot,” which expanded on ideas from “Dirigibles,” recalled that Perry approached him, wishing to “start this Indigenous forward, Indigenous-led comic book group.” Perry also wanted to adapt his short story into a graphic novel.

Shafer had already been in online contact with Macheras, who at the time was working on “Chickaloonies” with Silver through their production company, 80% Studios. “And right at that exact moment was when Nathan had reached out,” he recalled. “It just seemed like it was a perfect kind of match and tone in what the vision was. The energy seemed perfectly right.”

Soon Shafer, Macheras, Silver, Brame and Perry were in talks with one another, as well as with David Karabelnikoff and Melissa Shaginoff, about the shared universe concept. “It was just sort of like, we’ll have things in common,” Shafer said. “Like the snow goggles and domed cities and stuff. We’re just gonna intermix between them.” The idea for Luk’ae Tse’Taas was born. “Richard, I would say, glued us all together on a focus,” Shafer said of his late friend’s contributions to the project.

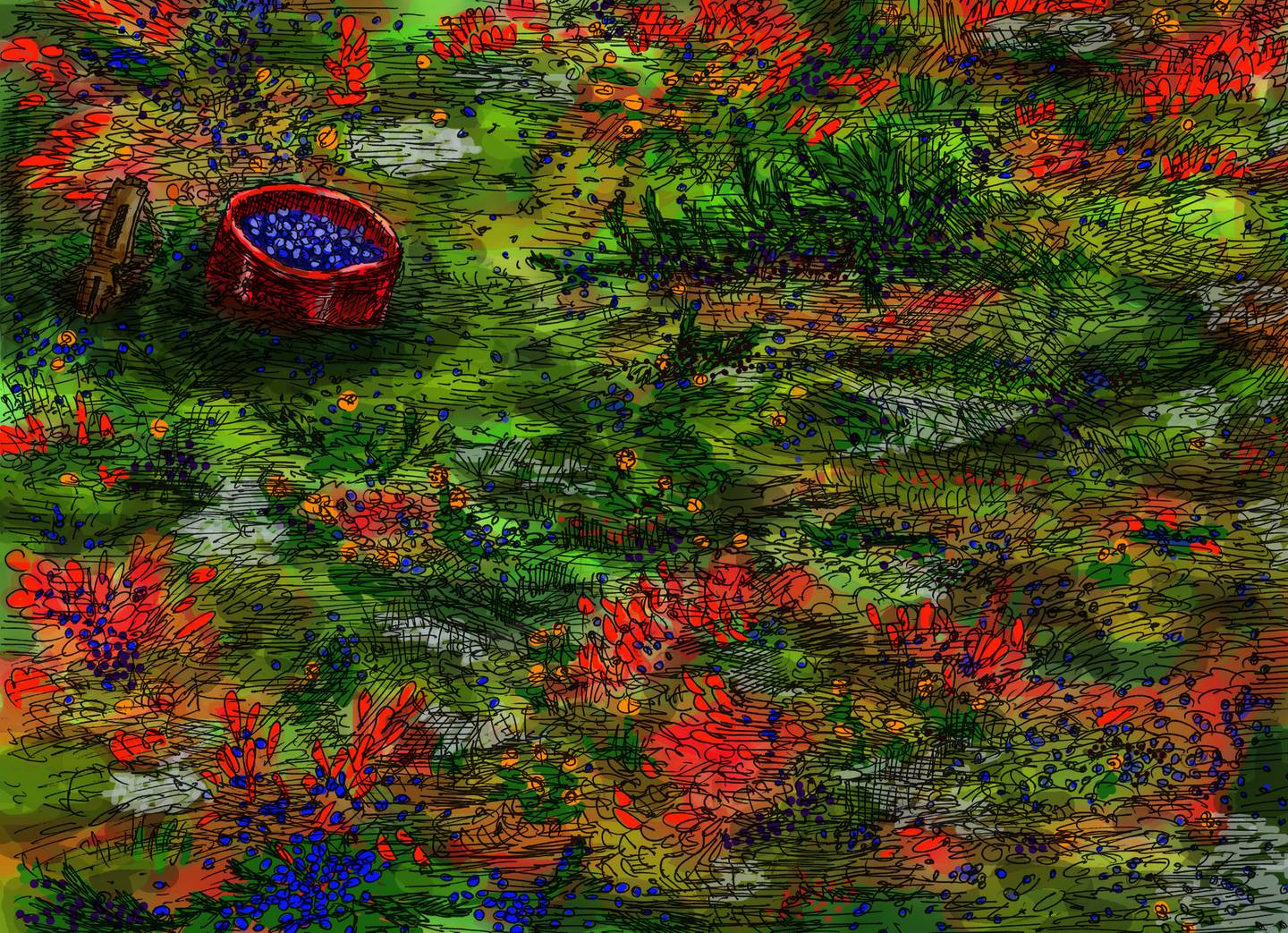

The first volume of “Chickaloonies” was published in 2021 (Volume 2 comes out this year), and the following year a trade paperback containing the first four issues of “Wintermoot” was released. Brame had begun artwork on Perry’s “Wildmen of Denali” script before the author’s death, and is continuing the job. “I’m interpreting it as more of a steampunk Alaska, I guess, but it’s more like diesel punk than it is steampunk,” he said.

That style will be in the same shared universe as the straightforward manga adventure in “Chickaloonies,” and the dreamlike “Wintermoot.” Shafer’s work draws inspiration from nonlinear legends, while Macheras looks first to the stories he grew up hearing.

“I went to the Ya Ne Dah Ah tribal school in Chickaloon village. So I was very closely tied to that part of my culture, that side of my family,” Macheras said. While he had drawn manga versions of Ya Ne Dah Ah legends, when he and Silver were developing their project, they wanted to expand on these tales, not just illustrate them.

“We didn’t want to tell existing old Ya Ne Dah Ah stories,” Macheras said. “We wanted to try and tell a new Ya Ne Dah Ah legend, or make a new Ahtna kind of comic. We created ‘Chickaloonies’ as a foundation where we could start telling new mythology, creating our own Ya Ne Dah Ah legends to explain the world that they live in.”

Shafer said “Wintermoot” took form slowly. The first couple of issues “looked very much like a conceptual new media artist put a comic book together,” he laughed. “I was perfectly happy with the idea of every page looking massively different and just getting across a couple of conceptual ideas.” Now that he’s learned the ropes of comic creation, he added, “I’ve got five more issues before the series ends. So I’m like just cranking them out at a mad click right now. I’ve been trying to release as many books as I can this year.”

Brame, meanwhile, has been busy resurrecting Lion Man, the first Black superhero, whose sole appearance was in the single issue of All-Negro Comics, published in 1947. “Lion Man exists throughout a bunch of different times and spaces and eras, which gives us a really good way to be able to tell stories,” he said. “The one we’re doing right now is sort of a 1960s blaxploitation, James Bond-style story. But the previous, we did sort of an illustrated fiction story that was more kind of like Prince Valiant style, like those single panel or three panel Sunday comics.”

The shared universe at Luk’ae Tse’Taas, the three agree, has room for all these ventures and more. “I honestly just imagine the ‘Wildmen of Denali’ and ‘Chickaloonies’ and even Dusty Funk or whatever David does, if not in the same universe, just adjacent,” Shafer said. “I could see any character from ‘Chickaloonies’ being in a panel in ‘Wintermoot’ or Dusty Funk, like it’s just sort of they’re in the same realities together.”