Medieval imagery wasn’t meant to be funny when it was made hundreds of years ago, but all over Instagram it has been remixed, captioned, and somehow reads as peak hilarious — depending on your sense of humor.

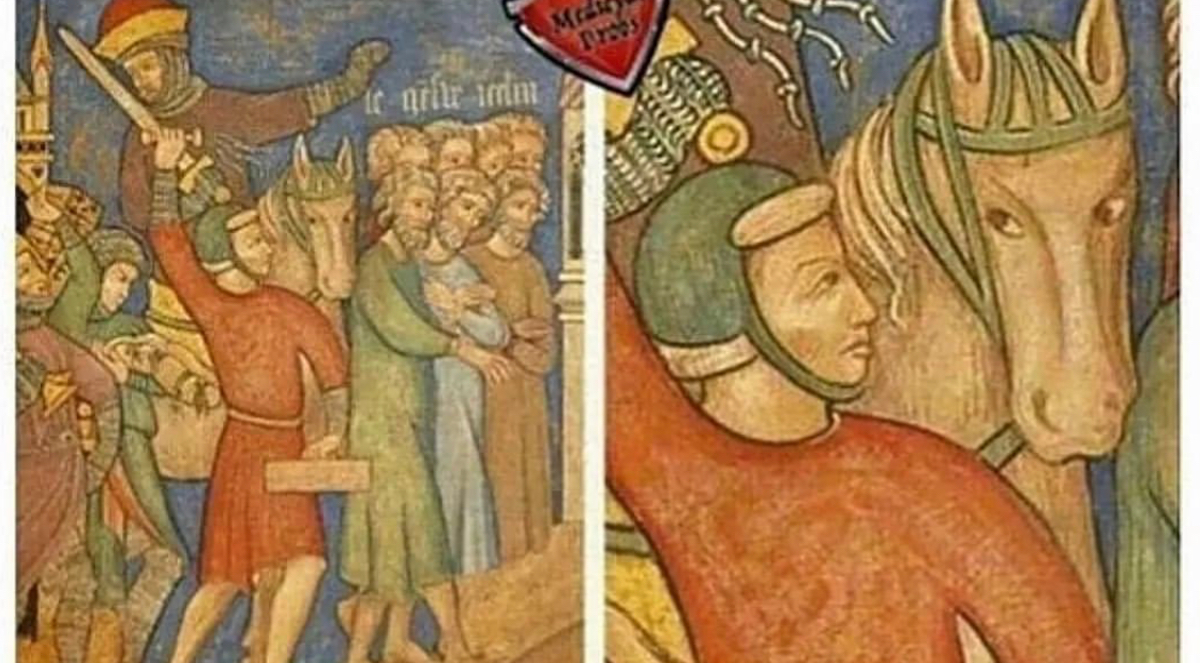

One evening while wasting time on the addictive social media platform, I came across a meme of a medieval battle scene; on the right, a horse was giving the sword-wielding dude some serious side-eye. The caption read: “When you acting hard in front of the squad but your horse knows you a bitch.”

I laid in bed staring at the tiny screen in my hands, laughing maniacally, posting it to my Instagram story and sending it to all my close friends. How could this seemingly arcane medieval imagery, previously confined to an art museum or, perhaps, a European crypt, feel so meme-able? Was it the meme’s imagery or the caption above it? I had to find out.

“It’s funny for the same reason that Black American Vernacular English is so sticky — because it references a level of servitude that we don’t want to admit,” said artist Kenya (Robinson), whose work often explores privilege, consumerism, and perceptions of gender, race, and ability. She noted that the text is written in Black American Vernacular English, also known as the language of social media. “The meme is showcasing the fact that we are all peasants,” she added.

That’s the text. But what about the image and the side-eye horse? It actually portrays the “Captivity of Jeholachin King of Israel,” which isn’t particularly funny. Babylonians destroy the Temple of Jerusalem, then lead the Jews into captivity. (As a Jewish person, this makes the meme feel very unfunny, and more like a story my grandma, or bubbe as we say, might have told over a holiday dinner.) The title refers to the defeated king of Jerusalem. The image, in fact, is not even an original — it’s a 19th-century reproduction.

But the fact that the image suddenly appears hilarious in this remixed context struck me. I tried to think back to my medieval art history class in college, but then remembered that I had dropped it shortly after I signed up.

“There’s something about the surprise of the medieval,” said Sonja Drimmer, a scholar of medieval European art, and associate professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

“One of the conceptions about the European Middle Ages has to do with blind piety, prudishness, but when people see imagery that defies that, the disjunction leads to laughter.”

Drimmer notes that the text in the memes “brings in the phenomenon of what are in-jokes from what I understand to be Black Twitter.” She compares this with “TikTok, [where] dance challenges began around Black dance challengers who aren’t getting any credit.”

Contrary to this cultural theft, there is a very awesome Tumblr, People of Color in European Art History, which responds to the whiteness of medieval art history.

Many art historical accounts hit up medieval imagery for jokes. Take another meme from the @artmemescentral account, where an almost transparent-looking dude wheels four people with black cloaks over their heads into an otherwise bleak, yet ornamental scene. The caption reads: “When you start to get serious with your girl and gotta say goodbye to all your h0es.”

“I think there is something about Western medieval art that seems like a safe target … some of the memes — like the side-eye horse, if it were sub-Saharan Africa — you could imagine meme-ifying it, and then imagine it becoming deeply problematic very quickly,” said Erik Inglis, professor of Medieval art history at Oberlin College. “I think with the very white faces of Western medieval art, it seems innocent. We are pretty willing to condescend to the Middle Ages, [which is] not fraught as it is to condescend to other ages.”

Most of the medieval art history memes come from broader art meme accounts, such as @artmemescentral or @classical_art_memes_official, though there are some discontinued accounts that focus only on medieval imagery, including @medievalmemes_, @medieval_meme, @medieval.memez, and @medieval_memes_and_facts.

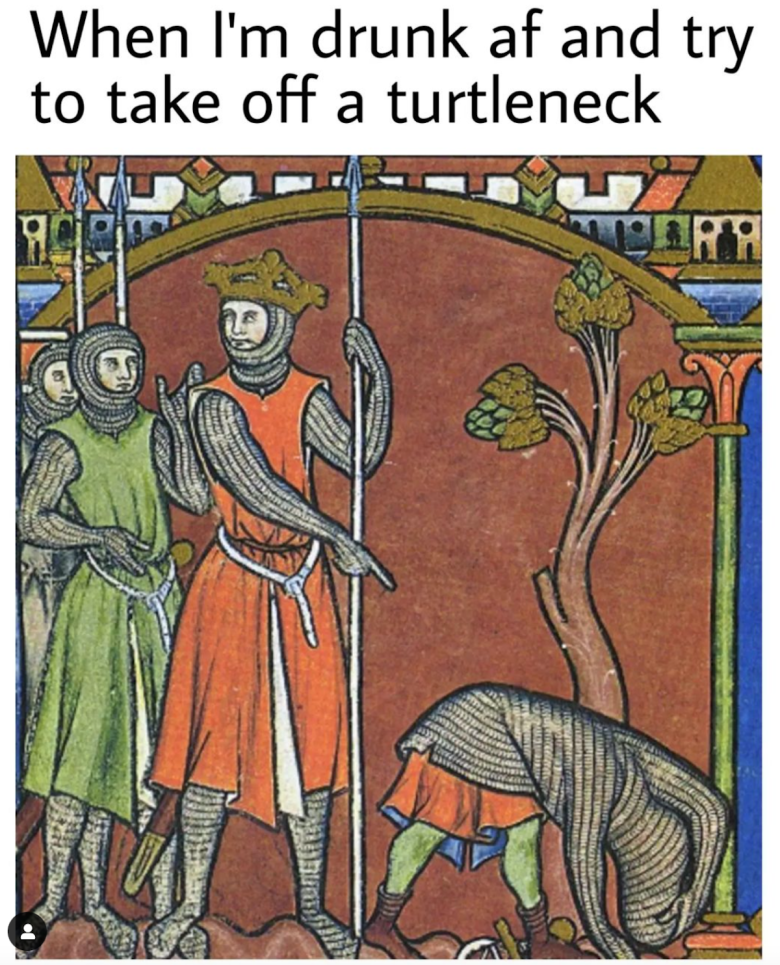

“Medieval imagery is so phone-friendly,” explained Cem A., an artist and curator who runs the popular art meme page @freeze_magazine (no association with Frieze magazine), and curatorial assistant at Documenta 15. “For me, its style is more simplified, representational, and cartoonish than our classical understanding of painting. Figures in these images usually have exaggerated (and therefore easier to grasp) relationships onto which you can build a meme. Its aesthetics works better on the compact screens of smartphones.”

At the same time, medieval imagery isn’t all just easy fodder for funny memes. It can “be racist and quite terrible, and ground zero for white supremacy,” said Drimmer.

The mob that stormed the United States Capitol Building on January 6, 2021, carried not only pro-Trump flags and red hats, but also symbols associated with the Crusades. The far Right’s use of medieval iconography gained steam after the September 11 attacks, with white supremacists picturing themselves as “modern Christian warriors fighting to preserve the idea of America as a white, Christian nation,” according to a report in Teen Vogue.

This is an even more troubling connection for academics and those who study the era, but also speaks to the layers upon layers of racialized remix culture that make up the ever-pervasive American visual pop culture that keeps on spreading.

There’s also an impulse to turn almost anything into a meme these days.

“The funny thing about retroactively searching through history to identify memes is that you start to see memes where they might never have existed before,” noted Daniel Shinbaum, a Berlin-based cultural critic and memes researcher. “Almost anything can start to look like a meme.”