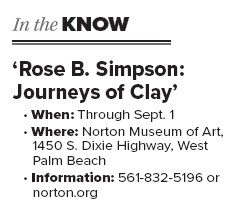

Apost-apocalyptic warrior sporting funky shades and bicycle-tire accessories watches a puzzled crowd enter and exit a pale-yellow gallery. The figure stands both modern and primitive, enigmatic and transparent.

A 118-inch-tall ladder resting on its back like a parachute conveys freedom and agency rather than subjugation.

This larger-than-life retro-futuristic clay sculpture titled “Great Lengths” required 70 generations of craftsmanship and at least three strong-willed maternal ancestors to come into existence. And that’s just the first ingredients in the mix. An ongoing exhibition at the Norton Museum of Art explores the gifted mind that conceived it.

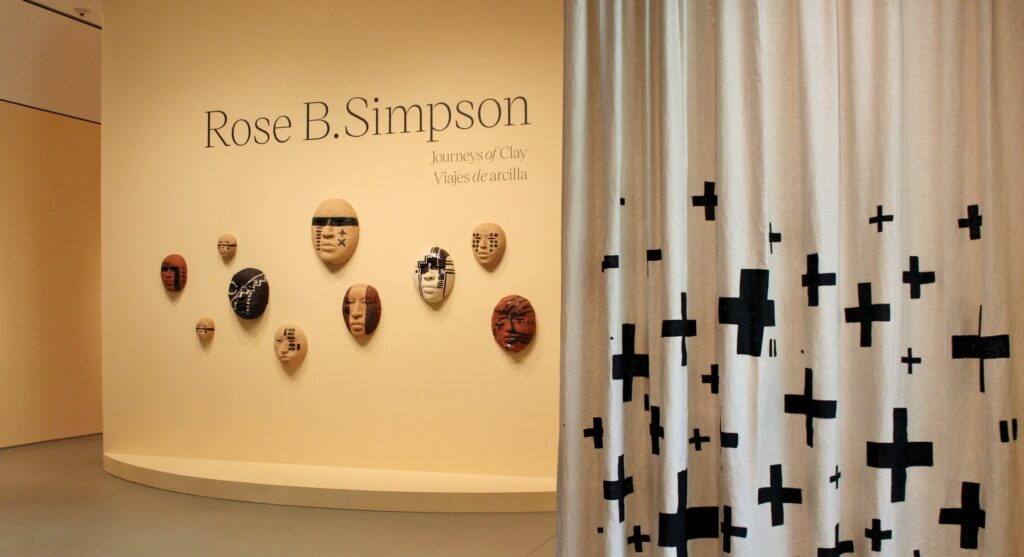

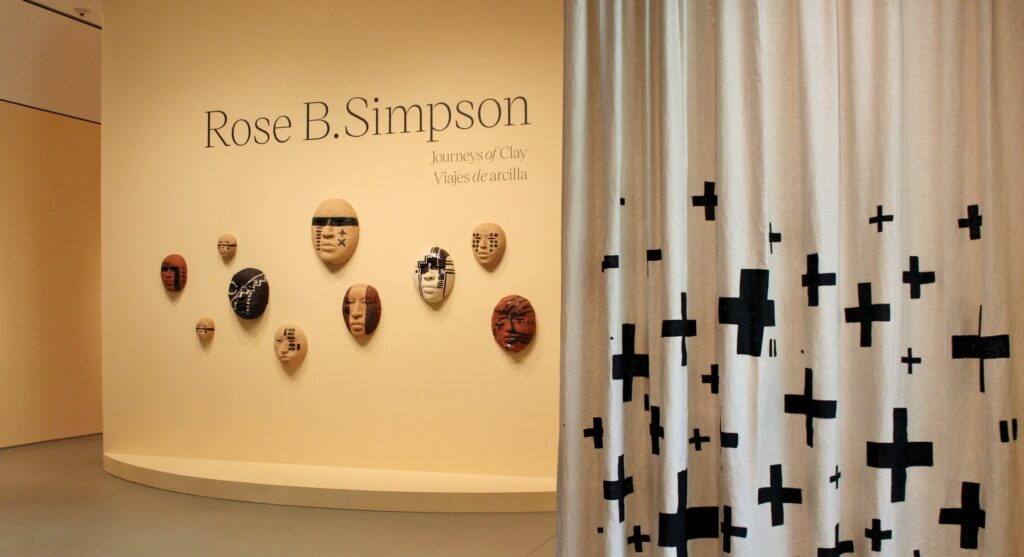

“Rose B. Simpson: Journeys of Clay” maps out the last decade of this Indigenous ceramicist’s career with a selection of about 40 visceral works ranging from totemic-like characters to 19-inch hanging masks and traditional vessels. Running through Sept. 1, the show includes four new pieces by Simpson. But what makes it truly special is the inclusion of pieces made by her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother. This is the first time works by Simpson and three of her matrilineal relatives, who profoundly influenced her voice, are exhibited together.

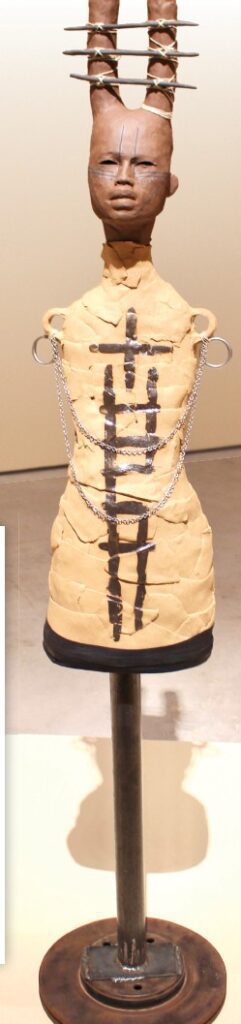

FAR LEFT: A work by ceraceramicist Rose B. SimpSimpson using ceramic, ic, glglaze and twine. LEFTLEFT: “What’s Up” by Rose B. Simpson. The artisartist used ceramic, glazeglaze, jute string, sterSEE ling ssilver and steel.

A member of Kha-’Po Owingeh, Santa Clara Pueblo, a Tewa tribe in New Mexico, Simpson marries ancestral and modern sensibilities to build sentinel-like figures out of clay, grout, twine, rope, leather, found objects and automobile hardware. The plus sign showering many of their torsos is in fact a star symbol meant to provide guidance and direction.

In “Growing Pains,” the body is stretched until it’s split in two only to have metal rods hold the halves together like a membrane. The figure, who sports an elongate neck and a bold head, sits atop a steel brake rotor. The star sign appears on its side while the torso is tattooed with dots meant for safeguarding. Like most of the works housed in the second gallery, the eyes have been carved out and the arms removed. Sensory organs such as the nose, the ears, and the mouth are typically spared from Simpson’s mutilation. The artist’s commentary on the pain brought on by change and growth is honest, raw, and far from formulaic.

She likes to protect her sculptures as they travel from and to museums by adorning them with beaded necklaces made from bone, wood and lava, such as that worn by the protagonist of “please hold 1.” Shown in a tight self-embrace, this is the only adult character granted arms. Self-worth comes from within rather than an active state. Arms equal action and a state of productivity. The piece reminds us that there’s value in repose and simply being.

Unparalleled in execution and directness, and varying in scale, Simpson’s sculptures embody bold interpretations of motherhood, family, gender identity, and the female body. There’s a certain fortitude and compassion to them. The thick skin developed from life experiences is evidenced by their scarred carapace, but they refuse to put up walls.

A selection of masks greets visitors at the entrance of the exhibition “Rose B. Simpson: Journeys of Clay.” GRETEL SARMIENTO / COURTESY PHOTOS

A prime example is “Cairn” in which a sphere bisects a mother’s body while her child, sitting on her shoulders, holds on to her. Protective markings in the shape of dots (another recurrent element throughout the show) cascade down her bandaged body, which portrays endurance. Simpson here equates her role as a mother and adviser to her daughter to a raised stack of stones that serves as a marker pointing to the right path. Having survived the voluntary gutting, the nurturing figure proceeds to support and care for her offspring.

The practice of creating earthenware goes back thousands of years and partially informs Simpson’s method. She descends from a sturdy line of ceramicists and potters spanning nearly 70 years but is not afraid to disrupt tradition. Her own twist comes by way of what she calls the “slap-slab” technique, which entails working with thin, fragile slabs of clay. This accelerates the drying process and adds a sense of urgency, which in turn requires quick judgment calls.

This is part of Simpson’s deliberate plan to leave space for flaws. She favors the anonymous over singular characteristics, the imperfect over the ideal. For the works to resonate and make us take stock of the human condition, they must bear a resemblance to humanity not perfection. It follows that with each passing minute, her clay universe grows more familiar and less esoteric.

In the first gallery, a gathering of works by three of her matrilineal relatives accompany the artist’s works and add context to her development and trajectory. They include “Big Clown Woman,” which features a large figure standing in the center of a platform. This is by Roxanne Swentzell, the artist’s mother, and a prolific sculptor in her own right. Simpson grew up watching her handle clay sourced directly from New Mexico’s land. The work transmits many of the sentiments coating the show, including emotions around womanhood, love, loss, safety and vulnerability. Small ceramic vases attributed to Rina Swentzell (her grandmother) and Rose “Gia” Naranjo (her great-grandmother) also make an appearance and celebrate the signature colors and qualities of Santa Clara Pueblo pottery.

This survey exhibition is the night installment in the Recognition of Art by Women (RAW) series, which seeks to rectify the gender disparity present in the art world through solo exhibitions focused on living female artists.

Walking “Journeys of Clay,” we get the strange feeling that we are seeing ceramic truly for the first time. This is ceramic not as a decorative plate or souvenir but as a presence that is at once demanding and benevolent. This is ceramic as a body that has been shattered, dissected, and put back together; as a mind torn between surrendering all its contents and keeping something for itself. ¦