Thornton Dial Sr. (1928 – 2016), “Birds Got to Have Somewhere to Roost,” Alabama, 2012. Wood, carpet … [+]

American Folk Art Museum“Home” can be a place. The four walls of a dwelling.

It can just as easily be a person or a thing.

The arms of a loved one. Your homies.

A pet. Food. A smell

Homes can be lost, found, built, sold, destroyed, change.

Homes can be real or imagined.

Homes can be welcoming or menacing.

While everyone literally has a home–a location where they live–some people never find a home–a place where they belong.

The American Folk Art Museum in New York examines the multifaced implications of “home” in “Somewhere to Roost,” an exhibition opened on April 12, 2024, on view through May 25, 2025. Featured are more than 60 paintings, textiles, photographs, and sculptures, exploring the ways artists evoke and construct ideas of “home.”

Taken both literally and metaphorically, “Somewhere to Roost” represents spaces where artists live and work, as well as places remembered or dreamed. The exhibition highlights experiences of immigration, incarceration, and housing insecurity, as well as visions of home that are playful, inventive, and unexpected.

The exhibition’s title is drawn from an artwork by Thornton Dial, Sr. (1928–2016), Birds Got to Have Somewhere to Roost (2012), which is among the works on view. Born on a former cotton plantation in the middle of nowhere in west-central Alabama, Dial’s teenage mother worked as a sharecropper. He grew up without a father and lived in poverty for much of his early life. He eventually moved to the Birmingham area where he worked as a laborer before being “discovered” by the art world.

Birds Got to Have Somewhere to Roost reflects the hardscrabble, makeshift, spit-and-bailing wire homes Dial knew and saw around him through its rough construction of wood, carpet scraps, corrugated tin, burlap and nails.

No mansion on the hill. No white picket fence. No American Dream.

Along with Dial, other giants of American Folk Art with work on view in the show include James Castle, Clementine Hunter, Nellie Mae Rowe, and Joseph E. Yoakum.

“The concept of ‘home’ evoked by the artists in this exhibition is intentionally open-ended and multidimensional, ranging from a functional piece of furniture like the Pennsylvania German Blanket Chest from 1790 to the photographs taken by Eugene and Marie Von Bruenchenhein at their home in Milwaukee,” Brooke Wyatt, exhibition curator and Luce Assistant Curator at the American Folk Art Museum, told Forbes.com. “There is the sense of home as a place of belonging and nurturance and the dual meaning of home as a house or structure that can extend to an enclosure or a space of containment–not necessarily a comfortable or inviting space.”

As in Dial’s case.

Or Frank Albert Jones’ Devil House.

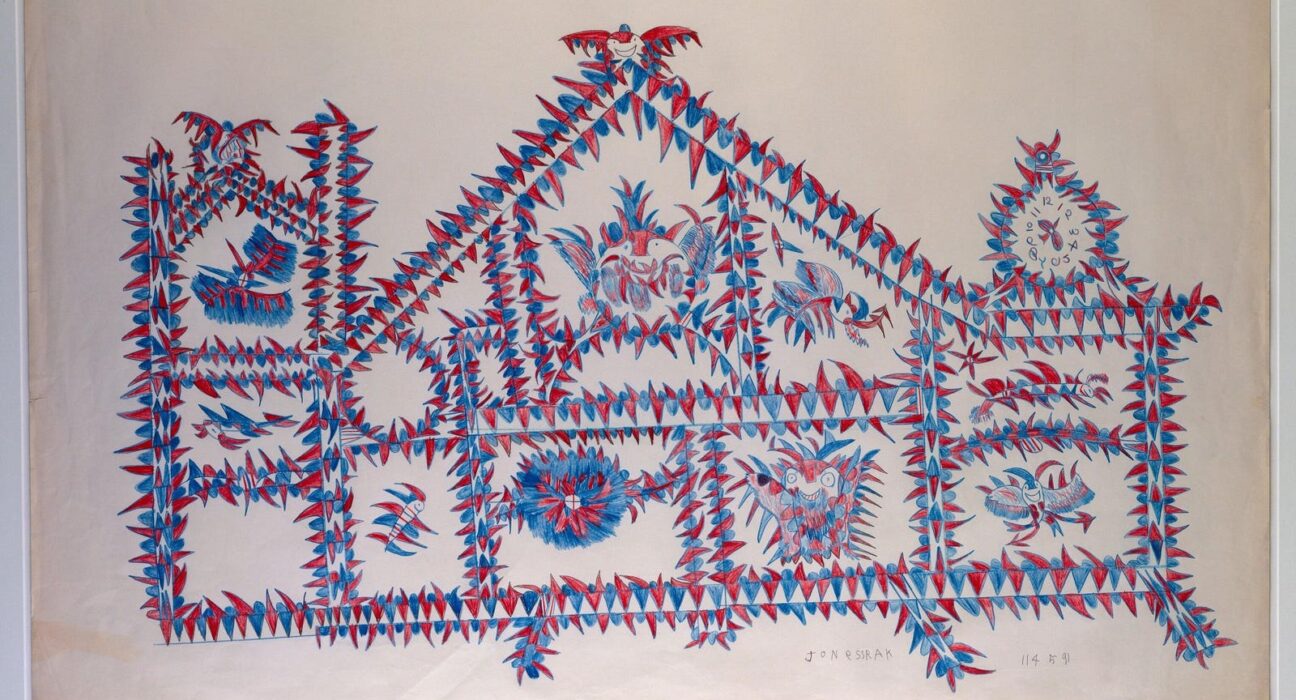

Frank Albert Jones (1900 – 1969), “Devil House,” Huntsville, Texas, c. 1964 – 1969. Colored pencil … [+]

Photo by Gavin Ashworth“Looking closely at this drawing, I am immediately struck by two elements that appear throughout the artist’s known body of work. The first is the way that Jones depicts a structure as a series of spaces that do not seem to allow passage between them, both by the thick walls, the absence of doorways, and the imposing and uniformly colored red and blue spikes that line each compartment,” Wyatt explains. “These spaces are stacked on top of one another and yet enclosed and contained, a fitting embodiment of a carceral space like the one where Jones was imprisoned when he made this drawing. The second element is the inhabitants of this space. Nearly every room in his Devil House contains a figure, a creature of some kind, some with wings or tails, some that seem to smile, and others who perch like gargoyles on the roof. Perhaps these beings are devils, and/or, perhaps the space that contains them is itself devilish.”

Returning to Eugene Von Bruenchenhein’s photographs, equal parts mundane, silly, and slightly risqué when centering his wife Marie–particularly for the 1940s and 50s–he positions home as an intimate space, a place to let your hair down, an idyll, if unusual construction–at least to outsiders looking in at his home, as he would surely think the same of our homes.

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein (1910 – 1983), “Untitled (Eugene and Marie),” Wisconsin, Milwaukee, c. … [+]

Photo by Gavin Ashworth.The exhibition also allowed Wyatt the opportunity of putting household items, like the Pennsylvania German Blanket Chest she mentioned, and quilts, on display alongside paintings, drawings, and photographs, further reinforcing the diverse interpretations of “home.”

“I had not worked directly with quilts before and was excited to engage with these large-scale and intricately crafted objects,” Wyatt said. “I have been thinking about how quilts physically embody a sense of home–being made in a domestic context, intended for domestic use, and specifically providing warmth and protection–and imagining how to put quilts into conversation with artworks that represent ideas of home in different ways.”

Within “Somewhere to Roost” every visitor will find their home represented because notions of home are universal, at the same time, no one will see their home, as “home” is equally personal and unique.

Home is in the church. Home is on the road.

A dream home. A cardboard box.

Housing has always been precious; it’s never been more expensive.

If we’re lucky, home is a friendly face. For far too many, it’s an angry face.

A happy place. A violent place.

Somewhere to go.

Somewhere to love.

Somewhere to leave.

Somewhere to roost.