- By Pauline McLean

- BBC Scotland arts correspondent

Image source, St Peter’s RC Church

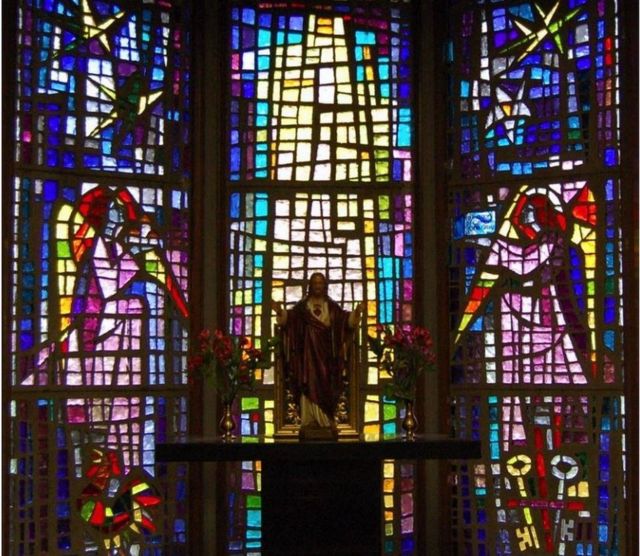

The “Symbols of St Peter” stained glass window was created by Pierre Fourmantraux and Whitefriars Glass in 1963

The requiem mass for the artist and writer John Byrne was held in a Catholic Church in an affluent suburb of Edinburgh.

Family and friends knew that he’d returned to the faith he held as a boy, growing up in Paisley. He and his wife Jeanine, a theatre lighting designer, were longstanding parishioners of St Peter’s and involved in many of the parish activities.

John even played guitar and sometimes a mouth organ in the folk group which performed at Sunday mass.

But the church was also the perfect place for the final days of one of Scotland’s finest and most prolific artists because it was built on art.

Hamilton born craftsman Thomas Hadden added his signature banana shaped birds on the Baptistery gate.

St Peter’s was the dream of a former poet turned priest called John Gray.

The son of a carpenter, he was born in a working class area of London in 1866 and became part of Oscar Wilde’s circle of friends.

Wilde was apparently so besotted with Gray, he named one of his most famous characters for him in The Picture of Dorian Gray. As a young poet, Gray apparently signed his letters to Wilde as “Dorian” but later distanced himself from the story.

In November 1892, he met the wealthy French poet Marc-Andre Raffalovich who was to become his lifelong friend and patron. For several years, they were part of a literary salon in 19th century London, dismissed by Oscar Wilde as more of a “saloon” than a “salon”.

Although they turned their backs on the decadent London scene, they were to revive the artistic salon in Edinburgh some years later.

Creating the church was dream of John Gray

In 1896, John Gray went to the Scots College in Rome (his family had Scottish ancestry) and became a priest. At the same time, Raffalovich converted to Catholicism and became a Dominican Brother.

Fr Gray’s first posting as a priest was to the sprawling Edinburgh parish of St Patricks in the Cowgate. Around 10,000 parishioners – mainly Irish immigrants – were crammed into tenements. It was a hugely challenging post but one in which Fr Gray was hugely respected. But it took its toll on his health and in 1904, he became ill with pneumonia.

Brother Raffalovich took him to Rome to recuperate, and as it became clear that Fr Gray couldn’t return to the Cowgate, a new idea began to form. Jerusha Hull McCormack writes in The Man Who Was Dorian Gray:

“During the long days of convalescence, he and Raffalovich piece out a possible future. It involves building a new church, largely with their own resources…Gray’s eye is suddenly caught by the small primitive church below his window, so typical of Rome: a square, Romanesque campanile low terracotta roofs around a courtyard…

There, he says, there is our church.”

Image source, St Peter’s RC Church

The Diocese of Edinburgh and St Andrews agreed that it was not only the poor of Edinburgh who required a church, and secured a site in the Morningside area of Edinburgh. Raffalovich wanted to cover all the costs, but Gray insisted that the community contributed to their own church.

The Scots architect Robert Lorimer was chosen to design the new church and the foundation stone was laid in 1906.

Gray and Raffalovich begin filling the church with art from their many connections. Personal commissions of paintings in the style of the Pre Raphaelites, a marble floor inlaid with little brass fishes in honour of St Peter, and the first Persian carpets seen in a public building in Edinburgh.

Their celebrated salons were revived in Edinburgh. Sunday dinners with academics, literati and visiting celebrities. The artist William Gillies – currently celebrated in an exhibition at the Royal Scottish Academy – was one of their regular visitors as were the artist sons of William Lorimer and Samuel Peploe.

Art continued to be commissioned for the church, including a range of decorative ironworks by the Hamilton-born craftsman Thomas Hadden, who often worked with Lorimer. His signature banana shaped birds can be seen on the Baptistry gate.

The church continued to gather artworks, long after the deaths of both Canon Gray and Andre Raffolovich in 1934, just four months apart. They include stained glass windows, sculptures, and the Stations of The Cross designed by John Kingsley Cook, head of the School of Design at Edinburgh College of Art. They are made from Dunbar sandstone, pebbles, marble and an old section of Edinburgh tramline.

The current parish priest Canon Kenneth Owens says the church continues to attract art lovers.

“We get lots of visitors, and a walking group include the church on their tour each year.

It gets lots of scholarly interest too. Several writers have visited and there’s currently an academic from St Andrews University working on a book.”

Image source, St Peter’s RC church

Byrne “detested” the church stations of the cross and had wanted to paint a new series

And even the parts of the church which have been altered, still retain their artistic credentials.

“Our eco toilet was created out of the baptistry which makes it one of the few facilities to have three beautiful stained glass windows.”

It remains a special place for Jeanine Byrne.

“John and I were very struck by the austere beauty of the interior when we first went there many years ago,” she says.

“John was aware of its colourful and romantic history but that wasn’t why we enjoyed going there. We love it because of the community and the priests, Monsignor Francis Kerr and then Father Kevin Douglas who celebrated Mass for John’s funeral. The community is very strong and close and John enjoyed that thoroughly.”

John was always happy to attend parish events and the only time I ever saw him willingly leave his easel and get spruced up to go out was on a Sunday. “

As for the art, it wasn’t all to his taste.

“John absolutely detested the stations of the cross – he thought they were dated, gloomy, clumsy and unclear. He spoke often of his wish to paint a new series of stations for St Peter’s but he ran out of time.”