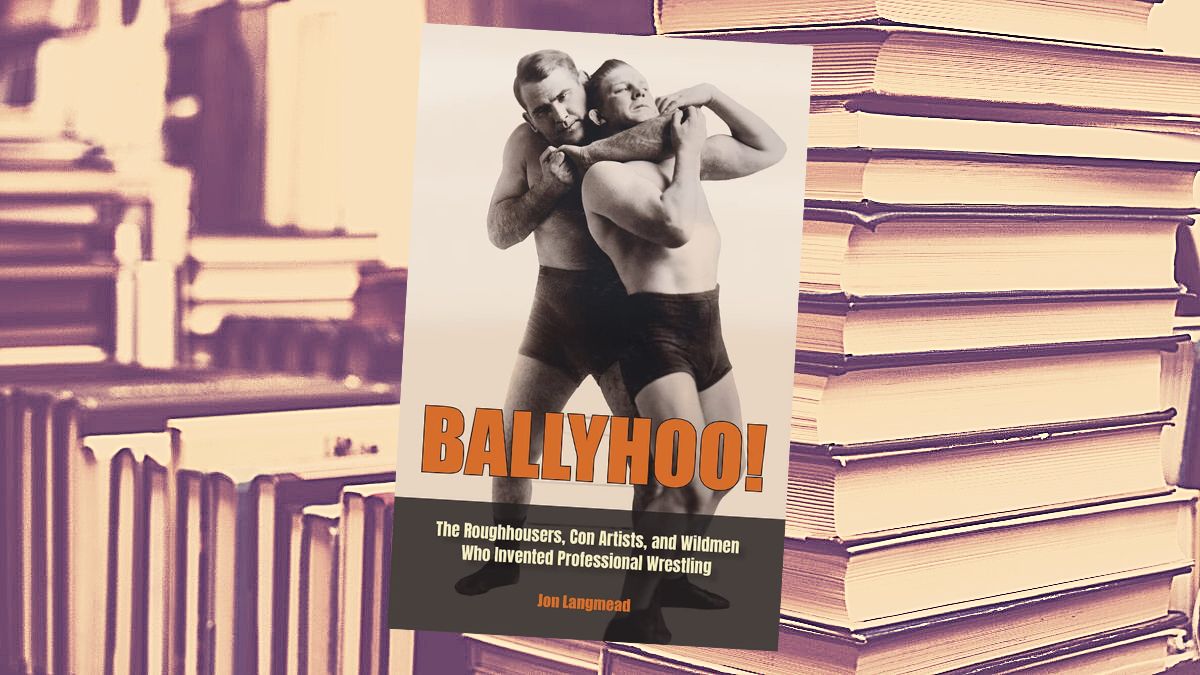

We’re pleased to be able to share an excerpt from the upcoming release, Ballyhoo!: The Roughhousers, Con Artists, and Wildmen Who Invented Professional Wrestling, by Jon Langmead, which will be out in February 2024 (University of Missouri Press).

CHAPTER 15

Jack Curley would never stop loving boxing, even when it barely had any room left for him. He was always happy to hold court with sportswriters and friends and tell them all about the mythical fights he’d witnessed and the legendary fighters he’d known. Given the chance, he’d opine for hours on just who would have beaten whom, had they been matched together in their prime, in a fair fight, on a clear, cool day. He’d lived long enough to see boxing pass from social menace to civic institution. When he was a young promoter, boxers risked jailtime for merely stepping into a prize ring. By the 1920s, they risked fines and suspensions from state commissions for not fighting or for being suspected of not giving it their all during a bout. Where fights were once held in cow pastures and other hilariously out-of-the-way locations, they were now elaborately promoted and held in specially built arenas. When Curley’s friend Jack Dempsey fought Gene Tunney in 1926 in Philadelphia, 120,000 people showed up to watch. Their rematch one year later in Chicago grossed more than $2 million.

Curley had only happened into professional wrestling, if he was being honest, as a sideline, but by 1928, he’d grown to embrace it. He’d become something of a grand old man in the sport, and his name was synonymous with it. Sportswriters loved to needle him and to try to get him to fess up to it all just being a big gag. Curley, though, always found a way to laugh it all off or redirect the conversation, only taking a strong stand when forced. “Wrestling comes first in my affection,” he wrote. “There is no accounting for this feeling. Maybe it is because wrestling is the most maligned and the most abused. Maybe it is the feeling of the mother, with a flock of good children, who bestows most favor upon the black sheep of her flock.” He knew the sport better than anyone else. Whether he wanted to admit it or not, he was made for it.

Over time, Curley started to wonder whether it was boxing or wrestling that represented the most basic technique for fighting. He’d spent most of his life collecting money from people interested in watching two men punch and pull and choke each other into semiconsciousness. In the first violent encounters among the first men, he asked himself, had a punch been thrown or a wristlock applied? He observed young children fighting and noted that they tended to bite and throw things. He noticed, too, that when a boxer lost his head during a bout, he would take hold of his opponent and try to throw them to the canvas. When wrestlers became enraged during a match, they began to throw punches. The more he considered the question, the further away an answer felt. In time, he learned to let the question lie. He knew he would never resolve it.

* * *

“I say that wrestling is not only a business,” wrote Los Angeles sportswriter Mark Kelly in 1929, “but an art.” Suggesting that professional wrestling was something other than good, honest competition would have offended Jack Curley, the renowned sportsman. But calling it art would have intrigued Jack Curley, the tireless aesthete. He knew that wrestling couldn’t hope to match boxing’s primordial appeal. As a sport, boxing needed no explanation. Wrestling, though, was a different story. He’d come to think that what people either appreciated or were repulsed by when it came to a pro wrestling show was the strange, engrossing sensation of watching a person squirm and shriek as their body was twisted and tossed in ways no human should be able to bear. “No one is born with a taste for wrestling,” he said. “It is a sport, a game that must be cultivated and, let us say, forced on the fellow that patronizes the box office.”

But the competition had grown stiffer than ever. Spurred by the success of Gus Sonnenberg, new promoters were getting involved in the business like never before, straining an already shallow pool of top-line talent. Fighting over performers and venues was now commonplace. Like all promoters, Curley had been forced to learn to work with the growing number of state athletic commissions, as they exerted varying degrees of control over who could wrestle whom, as well as when, and where. He’d been called a fake and a conman more times than he could count. And he had taken it all with a smile and a friendly word.

As the 1920s wore on, Curley’s financial problems only deepened. In 1928, he experienced his worst year yet, making “way minus, below nothing.” The wrestling business in New York looked at times as if it would never recover from the damage it had suffered in the early parts of the decade. Curley had flirted again with managing boxers and had tried but failed to stage a Jack Dempsey fight. He looked into bringing greyhound racing into New York. He imported cyclists from across Europe and staged a six-day bicycle race in the Bronx in January 1929. The event lost close to $15,000, and the cyclists were reduced to threatening lawsuits in order to receive their pay. That same month, Curley’s sometimes rival, sometimes business partner Tex Rickard died at the age of fifty-nine due to complications from an infected appendix. In June, Curley’s longtime associate, Harry Frazee, with whom he’d worked on the Johnson–Willard bout in Havana, died at only forty-eight. Two months later, one of Curley’s closest friends, the sportswriter and fight promoter Otto Floto, died at the age of sixty-six.

Curley was now fifty-two. He’d had his own major health scare in 1928, when an ear abscess had led to an infection in his mastoid bone. He’d had to borrow money from a friend to pay for the multiple operations that were required and was kept out of work for almost seven months. When he ran into reporter Joe Williams in October 1929 outside the Astor Hotel in Times Square, he must have been feeling reflective. He was planning to leave New York, he told Williams, and to retire to a sugar beet farm in Colorado. “This is my last season in the game. I’m getting a little old and tired, and I feel the need of a long rest,” Curley sighed. “I don’t expect ever to come back. Broadway doesn’t seem to mean much to me anymore, and the sport game has sort of gone past me. I don’t know how just to explain it.”

To prepare for what he thought would be his final year in the sports business, Curley brought in several new faces to help run his wrestling promotion. Rudy Miller, a German-born promoter who booked shows in the Bronx, was made an associate promoter. Toots Mondt, the well-known associate of Strangler Lewis and Billy Sandow, became Curley’s partner and his designated business heir.

From Chicago, Curley hired as his “Manager of Foreign Stars” a diminutive thirty-four-year-old Polish immigrant named Jack Pfefer. Born in Warsaw, Pfefer had come to the United States in 1921, at the age of twenty-six, working on a tour with Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova. Wrestling lore has it that he was the company’s manager, although by the best available records he was working instead as a porter and stagehand. After a love affair with a young opera singer in San Francisco ended badly, Pfefer vowed to stay a bachelor—a promise he kept. Over time, he developed a single-minded focus on professional wrestling. Though how he first got involved with the business is unknown, he came to specialize in getting coverage for his performers in the numerous foreign-language newspapers that catered to immigrant communities in major American cities.

Jack Curley, Hype Igoe, Jack Pfefer, and Joe Savoldi in 1933.

A mere five feet tall on his best day, jittery, with a prominent nose and a big, conspiratorial smile that took over half his face, Pfefer cut a slight but unforgettable figure. On the streets, he was often seen carrying a fashionable ivory-headed cane and wearing a pinky ring set with a diamond that wrestler Dave Levin remembered as being “half as big as [Pfefer] was. It was as big as a dime, really.” Pfefer spoke with a thick, almost affected, accent, and wore his raven-colored hair long. “Like I was a poet,” he said. “I don’t want to be mistook for a wrestler.” He liked to listen to opera to calm his nerves, and in his office, scattered among the framed portraits of wrestlers, he kept signed photographs of opera singers and a death mask of Beethoven. He claimed to sleep only four hours a day and to work the other twenty. Later in his life he favored photos of himself in which he was working two phones at once. “I am the hardest working man on Broadway,” he liked to say. “I am what you call Tynamic with a capital T.”

He accepted professional wrestling as performance as much as sport. For Jack Pfefer, in fact, it was hardly sport at all. “I’m not an athletic promoter,” he would later say. “I’m a theatrical man. Like Ziegfeld, or the Shuberts, maybe.” He sensed, too, a deeply sadistic impulse in his adopted country, a taste for blood that he was happy to exploit. In time, he would begin referring to his wrestlers as “freaks,” emphasizing their physical abnormalities. With the dime museums that had once been popular in many cities gone, Pfefer openly catered to people’s desire to see the unusual up-close. He clearly understood the shock value for American audiences cooked into seeing a 250-pound Russian with a curlicued mustache, like Ivan Poddubny, or a bald, barrel-shaped Hungarian who seemingly lacked a neck, like Ferenc Holubán. He had one of his wrestlers perform in an outfit made of leopard skin while others dressed in colorful clothes from their home country. Pfefer would come to harbor an antagonistic attitude toward his performers. “I treat them like a father,” he said of them, “like a mother beats up her baby.” He denigrated them openly, calling them bums and palookas, and was notorious for paying low wages and short-changing performers whenever he could. “They need me, but I don’t need them,” he declared. “I know where they grow.” Later in his life, he would be publicly assaulted by one wrestler, punched out in a locker room by another, and was said to have been dangled out of the window of his office on the tenth floor of the Times building by still another.

Nonetheless, Pfefer was curiously engaging and personable. Despite his public declarations to the contrary, he nurtured a deep love for professional wrestling. “He represented the best and the worst things about wrestling,” said Paul Boesch, a longtime wrestler and promoter who began his career working for Pfefer. Over time, Pfefer would amass what he called his “museum collection”—thousands of posters, show bills, newspaper clippings, photos, and correspondence that he stuffed into cardboard boxes. Unlike his contemporaries, he saw wrestling history as something worth preserving.

* * *

European wrestlers, “exotics” as they were sometimes called, had always been a significant part of Jack Curley’s shows, and his hiring of Pfefer was an acknowledgement of his desire to expand that portion of his business. Importing wrestlers could be an involved business, and it was financially risky. Arrangements needed to be made and honored, usually involving the exchange of dozens of letters and telegrams. Money was needed for photographs, boat and train tickets, passports, and other paperwork. There were government agencies to appease and constantly changing immigration laws and quotas to contend with.

Curley promoted a champion for each of New York City’s ethnic groups in the hopes of drawing them out to cheer for their favorite during his weekly shows at Brooklyn’s Ridgewood Grove or Manhattan’s St. Nicholas Arena. There were Jewish wrestlers (Abe Kaplan and Sammy Stein), Polish wrestlers (Leon Pinetzki), Hungarians (Sandor Szabo), Germans (Hans Steinke and Fritz Kley), and Italians (Renato Gardini and George Calza). Pfefer and Curley used their extensive connections throughout the world to scout new wrestlers and book them on US tours. The recruits would enter the country through Ellis Island, wrestle around New York for a season, and then be sent to tour the nation before either returning to their native land or staying and building a new life in America. Professional wrestling offered steady work that required no formal education or training and promised consistent, if sometimes unspectacular, pay at a time when both were difficult to come by. “They wrestle when they are told, where they are told, and usually how they are told,” wrote sportswriter Frank Menke. “If they don’t—well, they soon cease to have rassling jobs. For it’s easy to get an ice wagon driver to wrestle for $100 a week but it isn’t so easy for an ice wagon driver to get a job wrestling.”

One of the most successful non-American wrestlers in the 1920s was, in reality, not foreign-born at all. Reginald Siki was born Reginald Berry in Kansas City, Missouri, on December 28, 1899. Tall and muscular with an infectious smile, he had begun wrestling in 1923 and soon became one of the best-known Black athletes in America. Instead of being listed from Kansas City, promoters claimed he’d been born in Abyssinia, the predecessor of modern-day Ethiopia. They told reporters that his birthname was Dejatch Tedelba, and some of the most outrageous stories about him, such as one from Ring magazine, portrayed him as “breaking into cooked food life as a wild, wild tribesman, bedecked in three beads, war paint, a scowl, and a stone hammer.” In truth, he studied philosophy and photography, and was a world traveler.

Reginald Siki posing with trophies. Photo courtesy of Mark Hewitt

Siki wasn’t the first Black professional wrestler in America, but he was the first to sustain a career. Viro Small, the earliest known Black professional wrestler in America, began his career in the 1870s in Vermont. He performed around the Northeast before gaining more prominence in New York, where he performed at the first two locations of Madison Square Garden. A wrestler named Ila Vincent had performed in America in the early 1910s, but after struggling to find opponents, Vincent left to pursue his career in Russia and several European cities.

Siki was a thrilling performer, surprisingly agile given his height. He met with success early in his wrestling career, and there was immediate talk among sportswriters that he could be a challenger for the world heavyweight championship. No such match was ever made, however. Joe Stecher refused to wrestle Siki because he was Black, and Ed Lewis refused to wrestle him without being paid a substantial guarantee. “[Siki] is a giant in size and weight, with what I understand tremendous strength,” Lewis said. “I don’t propose to take a chance of losing the title without being well paid for it.”

After moving to Los Angeles to work for promoter Lou Daro, Siki was cast in multiple films, most famously 1927’s Tarzan and the Golden Lion. He was said to have lost out on a part in Cecil B. DeMille’s biblical epic The King of Kings only because DeMille considered him too large. Siki moved to New York in late 1927 to work for Jack Curley and in less than three months was appearing in main-event matches. After less than a year working in the city, he departed New York for unknown reasons, traveling to Europe in the spring of 1928. He would spend the next decade performing throughout Asia, Europe, and the United States.

* * *

Jack Pfefer and Toots Mondt.

With his new management team of Jack Pfefer, Toots Mondt, and Rudy Miller in place and ready to take over his business, Jack Curley prepared to walk away. But as 1930 began, he must have sensed an opportunity to turn things around. With the retirement of former champions Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney, boxing had been left with few marquee names. People, it seemed, were once again turning to wrestling. By March 1930, Curley’s wrestling shows were once again drawing sizeable crowds. It was nothing like his wild heyday of the late 1910s, but audiences were coming back to professional wrestling. Curley had even started staging matches at Madison Square Garden again, bringing an end to a six-year period in which the venerated arena hadn’t hosted a single night of wrestling.

With the increased gates, however, came increased oversight from William Muldoon and the New York State Athletic Commission. They handed out suspensions to Curley’s wrestlers for all kinds of offenses, from failing to appear for a match to unsportsmanlike behavior. The commission also established a working agreement with athletic commissions in other states, so that a suspension in one state could result in a wrestler being barred from working in several others as well.

Curley’s group was dealt what they thought constituted an insurmountable setback in April 1930, when Muldoon’s Commission declared that an evening of wrestling could only be advertised as an “exhibition” or as a “show”; use of the words “match” or “contest” in promotional material was disallowed without their special advance permission. Commissioner Muldoon offered no public comment on the decision after issuing it, but it was taken as having the dual intent of both protecting the public from dropping a dollar on a less than honest evening of sport and as a final attempt to safeguard his beloved sport of wrestling from those who would drag it into further disrepute.

On the day of the commission’s announcement, a crowd of Curley’s wrestlers blocked traffic in Union Square for an hour, shaking placards bearing the slogan “Doubting Muldoon” and depicting the commissioner with his foot on the neck of a wrestler while cracking a whip against the back of a promoter. Some writers took the decision as a death knell for wrestling, convinced that divorced from any official acknowledgement that a night at the matches might be on the level, spectators would keep away for good. To others, the idea that the Commission saw the need to act at all was, as one writer put it, “astonishingly ludicrous.” If it was impossible to prove matches were dishonest, why impugn the athletes in the first place? If it was all a known fake, why allow it at all?

The Commission’s decision would have served as a perfect opportunity for Curley to close the book on his adventures in professional wrestling. However, despite any promises he may have made to turn his business over to his new partners, something made him change his mind. Maybe he was broke and couldn’t afford to stop working. Maybe when the time came to say goodbye, he just couldn’t bring himself to walk away. Or maybe he had a notion, born of a well-honed instinct for sensing electricity collecting in the air, that something immense was on its way. Whatever it was, he decided that retirement could wait. He would stay on for whatever it was that was coming next.

RELATED LINKS