He was a giant of 20th-century art, but that doesn’t mean Pablo Picasso needed a big canvas.

Matchbook covers, postcards, restaurant napkins – they all served as makeshift sketchpads for the artist at moments of inspiration.

It is not surprising that some of Picasso’s sketchpads were smaller than, say, a compact disc cover – like the tiny one now on display at Manhattan’s Pace Gallery as part of “Picasso: 14 Sketchbooks”, an exhibition marking 50 years since the artist’s death.

A complete self-portrait in pencil peeks out, with deep and piercing eyes. It was 1918 and Picasso, then in his mid-30s, had just married ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova.

During a summer in balmy Biarritz, he painted on canvas but also kept this tiny notebook, filling it with scenes of their villa, the beach and the town, and sketches of coming paintings.

He also drafted a letter to his wife’s doctor and listed addresses of friends.

Brutal murder of farmers in Philippines changed this artist duo’s perspective

Brutal murder of farmers in Philippines changed this artist duo’s perspective

The exhibition is a collaboration with the Madrid foundation run by Picasso’s grandson, Bernard Ruiz-Picasso.

It comes nearly 40 years after the gallery’s 1986 show of Picasso sketchbooks, called “Je Suis le Cahier (I am the Sketchbook)” after a notation Picasso made on one of his pads.

In New York last week, the artist’s 1932 Femme à la montre (Woman with a Watch), portraying his muse Marie-Thérèse Walter, sold for US$139.4 million at Sotheby’s, making it the second most valuable Picasso ever sold at auction.

“He is the greatest artist of the modern period, and in many ways he thought of himself as a sketchbook,” says Pace chief executive Marc Glimcher, referring to Picasso’s efforts to refine his work through copious sketching.

He sounded almost evangelical when he urged the young people present to recognise that “everyone in this room sees the world differently because of Pablo Picasso”.

In an interview, Glimcher explains that he feels the world needs to be reminded of Picasso’s achievements. “When something becomes so iconic it becomes by necessity oversimplified,” he says. “People say, ‘Oh, Picasso, got it’. We have to make sure they do get it.”

The show, in one large gallery, is organised chronologically, spanning 1900 to 1959.

Each of the 14 sketchbooks is presented in context with what was going on in his life – including his romantic relationships, which figured so prominently in his work.

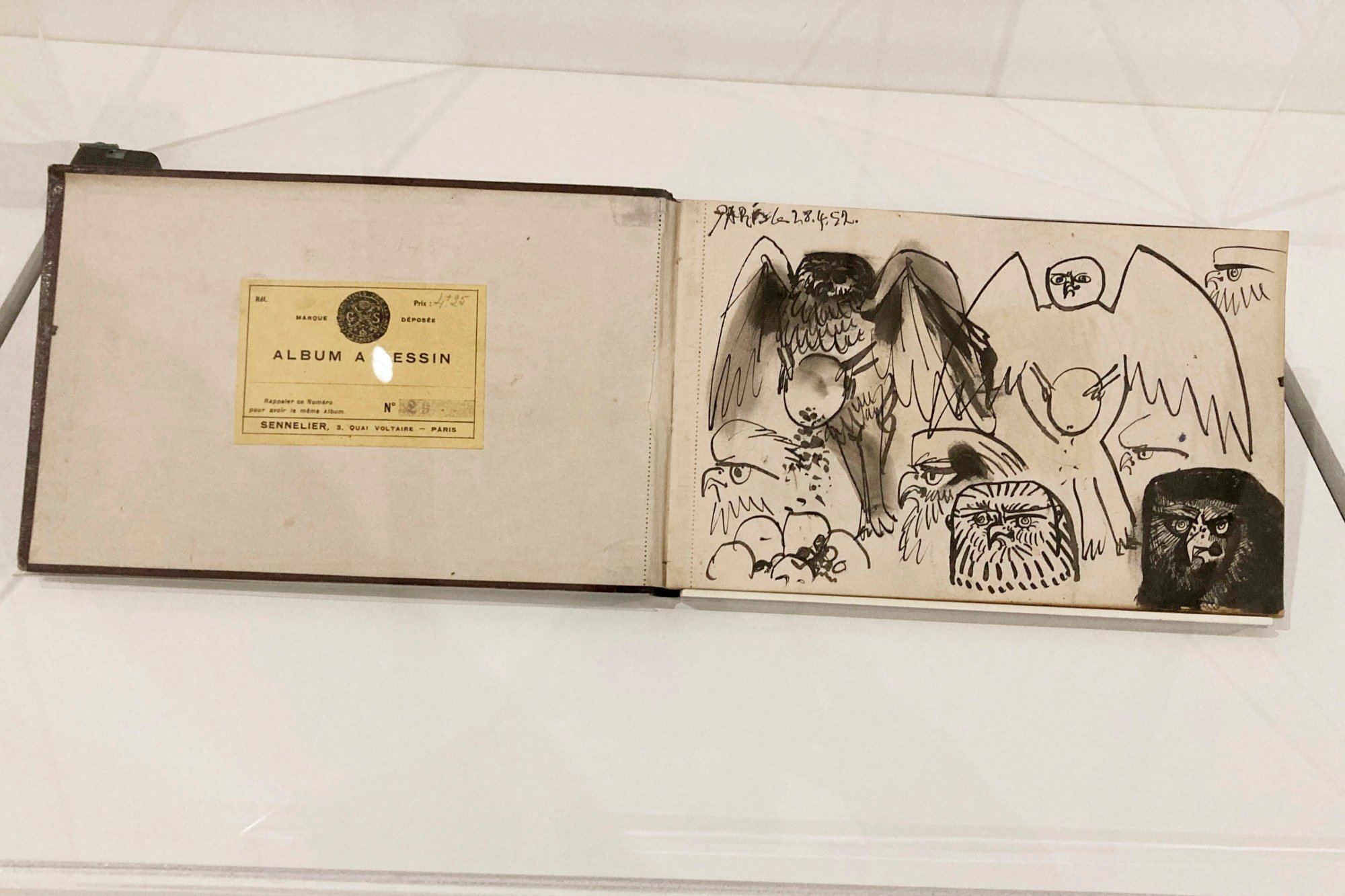

Many of the sketches are early versions of famed paintings like Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), for which one sketchbook tests various figure renderings; Dora Maar in an Armchair (1939); and his “War and Peace” murals, for a chapel in southern France, that were finished in 1952.

There is also a film of Picasso, shirtless and in shorts, preparing for those giant murals, needing a ladder to reach the top of his canvas – and reminding us of the dimension of some of his masterworks.

But elsewhere in the show, the gems are miniature. Some of the images are fanciful, like the monsters and clownlike figures, some in bright blue and red pencil, from a 1956-1957 sketchbook that resembles a children’s book.

Others feel precise and more technical, like the ink drawings in his Juan-les-Pins sketchbooks, from 1924, in which he experiments with shapes of guitars and other objects through patterns of dots and lines, known as “constellations”. A long poem also appears in one of the sketchbooks, translated in an accompanying catalogue.

With each sketchbook open to only one page, how to uncover the rest? The gallery’s solution is to provide subsequent pages in video displays on a loop.

Ruiz-Picasso, the artist’s grandson, says the sketchbooks deserve a fresh look because much has happened in the past few decades in terms of research into Picasso’s work and the context in which it was produced.

A blank canvas: how an unlovely Macau house became a whimsical art cave

A blank canvas: how an unlovely Macau house became a whimsical art cave

“We have better information now about what he was doing,” he says.

Ruiz-Picasso, who was 13 when his grandfather died, remembers children not being entirely welcome in the studio where the artist painted in Mougins, France, where he lived out his later years. But elsewhere in the home, he remembers him always sketching “until the last piece of paper available”.

“He was permanently doing something,” Ruiz-Picasso says.

Picasso: 14 Sketchbooks runs at The Pace Gallery until December 22.