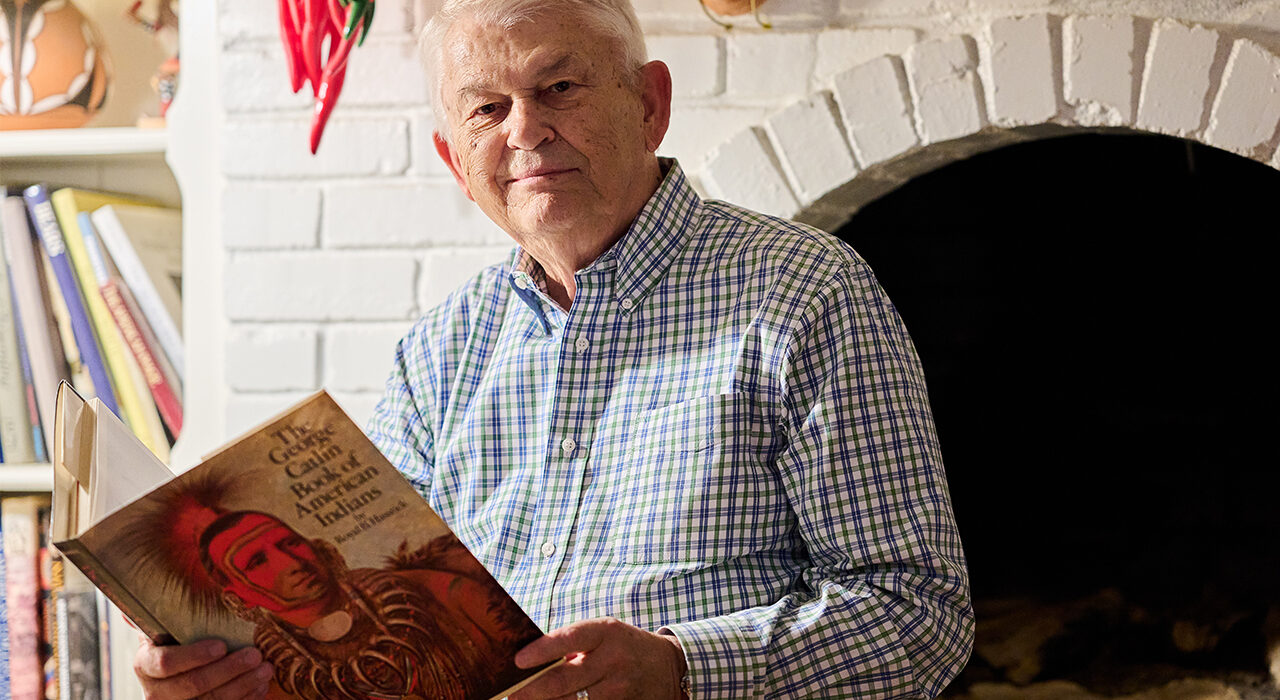

Dr. R. David Edmunds, M.A. ’66, LL.D. ’02, is an authority on Native American history and culture who has gained the status through more than 50 years of teaching and scholarship. He’s equally adept at delivering a lecture or keynote address, offering commentary on a History Channel documentary, or providing expert testimony in a courtroom.

Native American history has been his life’s work. And he is part of that history.

Growing up in rural Macon County, Edmunds was aware of his Native American heritage. His great-grandmother, “Pachiee,” was three-quarters Cherokee; she spoke fluent Cherokee and broken English, according to Edmunds.

But it wasn’t until Edmunds became a young teacher that he immersed himself in Native American history.

After earning his undergraduate degree at Millikin University in 1961, he started his teaching career at Bloomington High School while simultaneously pursuing a master’s degree at Illinois State University. As part of his studies, he wrote a thesis on the history of the Kickapoos, an important tribe in Illinois history. The project provided an opportunity for Edmunds to research his own lineage, and a pursuit of his personal origin story sparked a curiosity that turned into a 50-plus-year career.

The recipient of an honorary degree from Illinois State in 2002, Edmunds has taught at the University of Wyoming, Texas Christian University, the University of California, UCLA, Indiana University, and finally the University of Texas at Dallas. Retired from teaching since 2015, Edmunds is still very much an educator.

He delivers keynotes and leads workshops like one this summer for teachers in Nebraska on the importance of teaching students about Native American history. He occasionally welcomes into his suburban Dallas home a production crew from a docuseries or podcast seeking an authority on Native American history. He continues to write, and his latest book, Voices in the Drum: Narratives from the Native American Past, was published last month; it’s his first foray into historical fiction. He’s increasingly serving as a consultant and expert witness in court cases impacting Native populations.

At 84 years old—and technically “retired”—Edmunds’ expertise remains in high demand, and he still enjoys the work.

“If I hadn’t made a profession of this, it would have been a lifelong avocation,” he said. “I’m very fortunate to get paid for what would have been a hobby.”

Part of his duty as a historian is setting the record straight, and Edmunds has spent much of his career dispelling popular Native American myths. One is that most Native Americans live only in the Western United States. “Tribal people don’t all live on reservations in the American West,” he said. “More than half live in major urban areas.”

Another misguided notion, he said, is that Native Americans are a disappearing people. Between 2010 and 2020, the Native American and Alaska Native population in the United States almost doubled, increasing from 5.2 million to 9.7 million, according to the latest census data. “The idea of the ‘vanishing red man’ couldn’t be further from the truth as the numbers are really expanding rapidly,” Edmunds said. “Many tribal people may now have mixed lineages, but they have retained their tribal affiliation.”

Edmunds also debunks the idea that Native Americans were a primitive people who hadn’t developed complex societies prior to the arrival of European settlers. He points to the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site as an example of a sophisticated pre-Columbian Native American city. Cahokia is a World Heritage Site located across the Mississippi River from St. Louis.

“Cahokia had an open market with a big plaza and had 30,000 people living there, including its suburbs,” Edmunds said of the 13th century community. “It was bigger than any city in Germany or Belgium, and it was larger than London was at that time. It was tied into a trade network that stretched from Lake Superior to the north, Yellowstone to the west, and the Gulf of Mexico going south.

“Cahokia was a definite city by world terms. Civilization was already flourishing in North America.”

Edmunds is also quick to note that Native American history surrounds us. That’s true for Illinois State University and Central Illinois. The Kickapoos, whom Edmunds first wrote about as an Illinois State student, had villages along the Mackinaw River near Bloomington and the Salt Fork of the Sangamon River, which cuts a swath across the middle of the state.

“I think it’s important to understand that many tribal people today function in the mainstream. We still retain a strong sense of place, a strong sense of family, and certainly a strong sense of identity, and I think that’s very important.”

—Dr. R. David Edmunds

“This area has one of the richest Native American histories in all of Illinois,” Edmunds said. “In McLean County, there’s a very important spot near Saybrook and Arrowsmith, not far from Downs, which was the site of the Grand Village of the Kickapoos. During the War of 1812, it was a major staging area for raids against Southern Illinois, Missouri, and St. Louis.”

Edmunds’ newest title is that of consultant to tribal people in land and water disputes. That work requires him to interpret treaties, some signed more than 200 years ago, and occasionally provide expert testimony. There are usually several cases he’s following closely.

In one prominent case this summer, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the Navajo Nation in a dispute over water rights related to the drought-stricken Colorado River. Edmunds predicts there is more to come in the case. “The tribes feel that they should have adequate water,” he said. “That fight is not over.”

Another case he monitored was decided in July when the Supreme Court upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), a federal law enacted in 1978 that gives preference to Native American families who want to adopt or foster Native American children. On a 7-2 vote, the court rejected a white couple’s claim that the law was discriminatory. North Dakota recently adopted some portions of the law into its state law, and news reports indicate that other states will follow.

“There was a major attempt in the early part of the 20th century for non-Native Americans to adopt Native American children,” Edmunds said. “When this happens, the children lose all their aunts and uncles. But because of deep family ties, it’s hard to be an orphan as a Native American, since almost all tribal family networks are extended through cousins and second cousins. At a powwow, the first thing you do is go around and find out who you’re related to.”

Edmunds remains involved in parallel efforts to preserve history and secure a better future for Native Americans. He does so by combining his skills as an educator, historian, researcher, and advocate. He’s witnessed signs of slow progress but admits much is still to be done. “Things could be worse, but it could be a lot better,” he said. “Now, tribal chairs are well-educated. Many have MBAs. The fights are now in the courts and not on the prairie.”

If there’s one thing to be taken away from one of Edmunds’ keynotes or TV appearances or his latest book, he hopes it’s a recognition that Native Americans are Americans, and Native American history is American history.

“I think it’s important to understand that many tribal people today function in the mainstream,” he said. “We still retain a strong sense of place, a strong sense of family, and certainly a strong sense of identity, and I think that’s very important.”

Illinois State University’s chapter of TRIBE—a registered student organization (RSO) with an acronym that stands for Teaching, Reviving, Indigenizing, Beautifying, and Equalizing—was founded in 2021 with a goal to spread cultural awareness and equality on campus and give back to Indigenous communities.

TRIBE is open to all students interested in preserving and honoring Native American history. Anyone interested in learning more can contact or visit Illinois State’s Multicultural Center.