Bright colors. Dark subjects.

Jim Denomie’s vivid paintings tell stories of colonialism, oil pipelines, violence. Stories the artist himself wasn’t aware of until adulthood.

So it goes for a Native American assimilated into white culture through the machinery that culture has designed to do so. Indian Urban Relocation. The generational trauma of Indian Boarding Schools. Popular culture. A public education system centered on white nationalism.

Learning his history and culture, and acquiring the artistic tools necessary to express what he was feeling visually, would come later for Denomie (Ojibwe, Lac Courte Oreilles Band, 1955–2022).

After dropping out of high school.

He recognized traditional schooling wasn’t for him and asked his counselor to help him attend a school focused on arts education. She thought that was a dead end. He said he’d drop out if she didn’t. She didn’t care.

After a near 20-year stretch of aimless partying and alcoholism.

After working long days in construction and trying to raise a family.

Jim Denomie, paragon of the late bloomer.

He sobered up in 1989, got a GED, and the next year enrolled at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis where he had and would spend most of his life. Like millions of others, he found himself at college, Denomie just happened to be in his mid-30s when doing so.

On campus, he became involved with the Native American community, connecting to the heritage he hadn’t previously. Future parents raised in the horrors of the boarding school era, like Denomie’s–oftentimes the scars are too deep, the attempts at cultural erasure too successful, to pass customary ways along.

At the University of Minnesota he would learn about his past and establish a future. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in American Indian studies. What he learned was painful, and then, candidly, pissed him off. Broken treaties, genocide and the like.

He simultaneously pursued his boyhood desire of artmaking, the one amputated by the counselor. In 1995 he also secured a Bachelor of Fine Arts in art and began pursing his painting career.

The culmination of his dual journeys into Native American history and fine art can be seen now through March 24, 2024, during “The Lyrical Artwork of Jim Denomie,” an exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art highlighting Denomie’s singular vision and signature style over the second half of his career (2007–22).

Color

Denomie could be described as a colorist. His primary attraction was to color and he noticed it everywhere–sunsets, birds, fish, frogs, minerals. He often told the story of how color theory was his most important, transformative class at university.

Pinks, purples, fuchsia.

His palate is deep and rich with nonrepresentational hues recalling the Fauves of the early 20th century.

Denomie’s paintings routinely engage with art history. The Last Supper. Manet. Nighthawks. Vincent van Gogh boxing Mike Tyson.

“Beyond his formal education, Jim was a lifelong student,” Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art and the Minnesota Artist Exhibition Project Coordinator at the Minneapolis Institute of Art Nicole Soukup told Forbes.com. “He was a regular museum visitor to not only the Minneapolis Institute of Art, but museums across the country. His sketchbooks list artists and artworks he saw at museums like Brooklyn, The Met, etc. His studio was filled with exhibition catalogues and books.”

While his work has the freedom and visionary quality of self-taught or folk artists, Denomie doesn’t belong to that category. He was highly trained. Deeply studied.

Spiritual, yes.

Indigenous, yes.

Descending from Western art traditions, also, yes.

The nudes, the color, the continuation of art historical movements descended from Europe by an artist not similarly descended recall the paintings of Bob Thompson and Robert Colescott. Denomie and Colescott further share a bawdiness and absurdity.

Denomie’s art has acutely been descried as “surreal, satirical,” “a Far Side cartoon painted by Hieronymus Bosch.” Bingo.

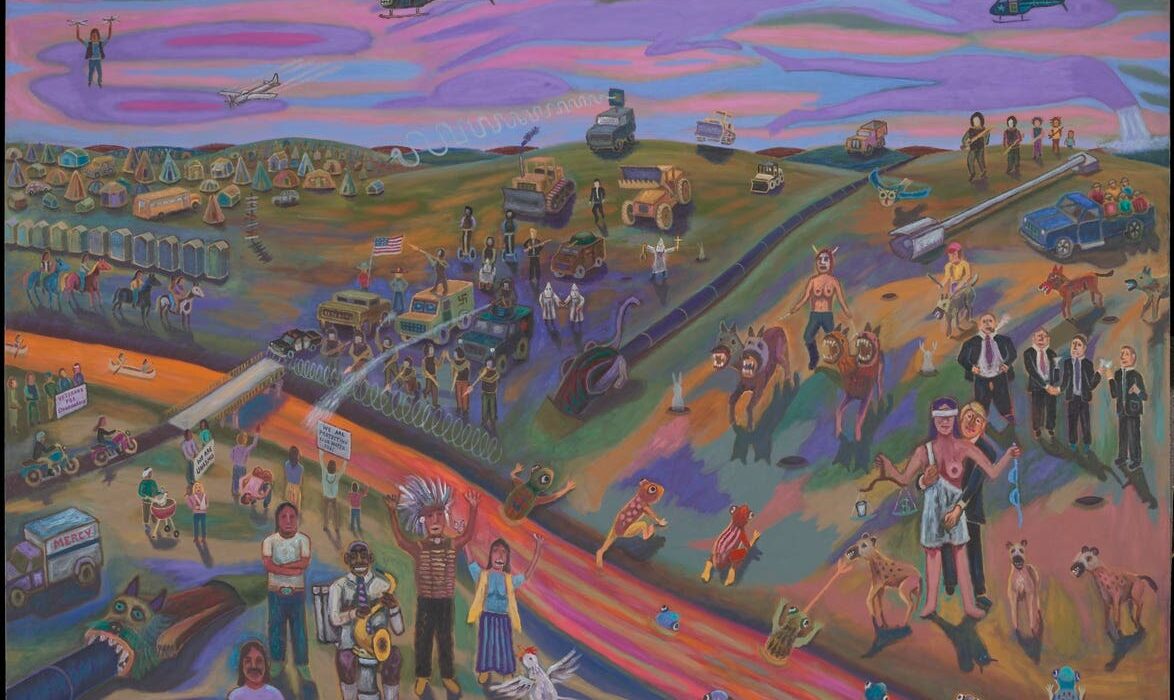

“If you look at his oeuvre, you can see tropes from the history of European art—like the Arcadian landscape. Of course, he gave it his own spin,” Soukup explains. “However, in works like Standing Rock—2016, you see the classic landscape as a stage-like setting. Jim used elements like a river and pipeline to lead the viewer’s eye from foreground to mid-ground. The rounding hills create a clear horizon line. Using a tight framework allowed Jim to focus on the hyper-layered vignettes and details in his genre and history paintings.”

The painting recalls Bosch or Bruegel. It’s stuffed with figures and action, often bizarre and macabre. Donald Trump gropes an Indigenous lady justice. Oil pipelines, Cerberus, Klansmen, swastikas, military vehicles, helicopters, people, animals, a tipi encampment, porta potties.

Denomie’s “Standing Rock” series explores his response to the Dakota Access Pipeline protests at the Standing Rock Reservation in 2016–17. Following the exhibition of his “Standing Rock” series at the esteemed Bockley Gallery in Minneapolis which represented Denomie since 2007 and has as a specialty representing Native American artists, Soukup asked the artist, “What would an exhibition at Mia look like?”

“The Lyrical Artwork of Jim Denomie”

It looks big, colorful, confrontational.

Figures everywhere.

Nudes.

Men and women with deer heads who came to him in dreams.

Spiritual. Mystical.

Witches.

Denomie liked witches. Even dated one.

Sturgeons, frogs, pileated woodpeckers.

Drawing inspiration from lived experiences, pop culture, Anishinaabe–what many Ojibwe prefer to call themselves–traditions, and American histories, Denomie’s work forwards provocative stories of being Native in America.

“The boundary between Jim’s portrayal of Anishinaabe traditions and beliefs, what he saw in his dreams, and what is realized on the canvas is a thin, porous line. If visitors are familiar with Anishinaabe beliefs, they may find elements in nearly every work of art,” Soukup said. “For those of us like myself who are not Native, we can readily see the spirits that fill the skies and landscapes. A notable example is the spirits in the sky pouring water onto the Earth in the painting Standing Rock–2016.”

Despite the emotional weight of his subject matter, visitors will be excused from chuckling here and there. Denomie, as with many contemporary Native American artists, brings a rapier’s wit and highly attuned sense of humor into his paintings.

The exhibition features approximately 60 artworks, some well-known, others never before seen in public. On display together for the first time are his large-scale paintings, unfinished works, rare sculpture and sketchbooks.

And a curious series of assemblages.

“The funny thing about Jim is that he was always making something out of the hundreds of trinkets and bobbles that filled the tables in his studio and garage,” Soukup said. “Jim worked across media, but rarely showed sculpture. He filled his studio with these masks and painted found objects. I think he found humor and joy in making them. For example, Diabetic Spirit, or the untitled (fish) made from his shoe and five-iron. Right before he passed, Jim was dynamically returning to sculpture.”

Cancer took Denomie’s life in late winter 2022. He and Soukup were deep into planning the exhibition, a process he was highly engaged with from the start. No one expected him to go so quick. The show was intended as a mid-career survey.

Denomie’s artmaking started late and ended early, in between, a prince of a man and an extraordinary artist.