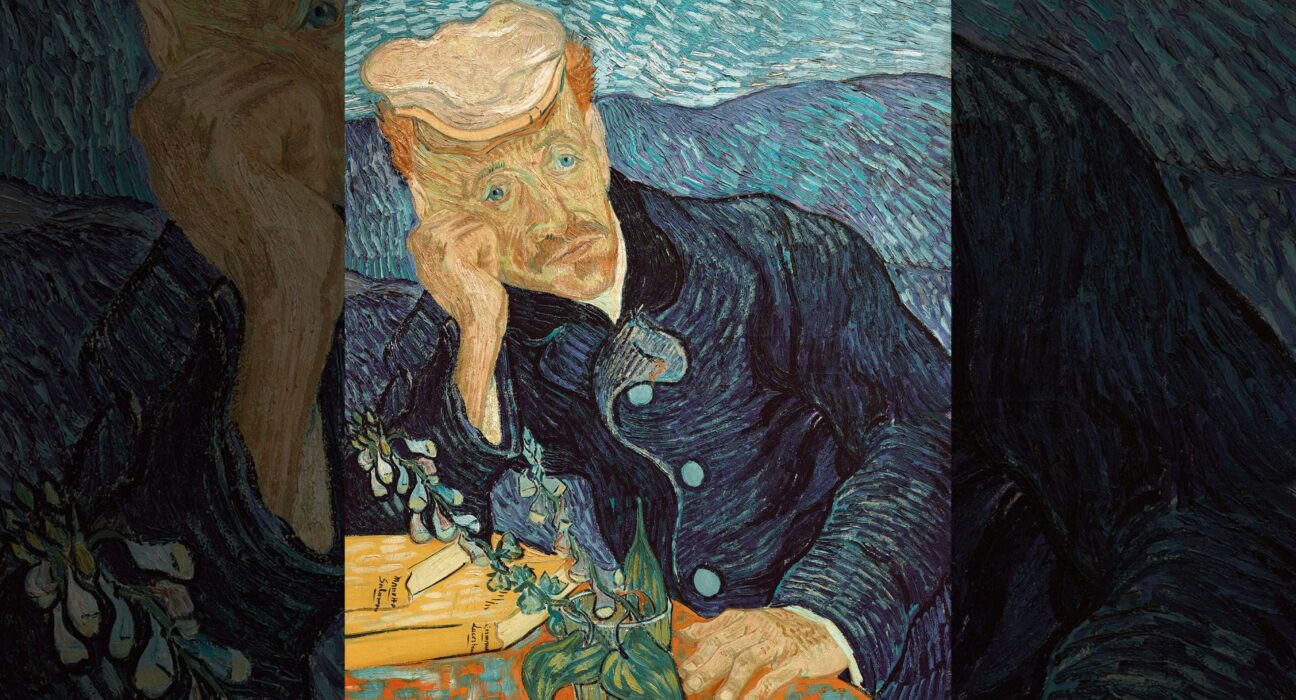

Appointed after Vincent Van Gogh’s discharge from the Saint-Paul Asylum in Saint-Rémy, Dr Paul Gachet was always more than a medic. Gachet and Van Gogh shared a close affinity; both were artists and prone to mental health problems, and when Van Gogh painted his doctor, he did so in the pose of “melancholia”, sighing over a foxglove, his homoeopathic treatment of choice. Gachet would later return the favour on paper, with a drawing of Van Gogh, his friend, on his deathbed, signed with his pseudonym, Paul van Ryssel (“Paul of Lille”). In reality, he said goodbye with a solitary sunflower left on top of the soil.

To see men of the 1890s being so open about their own mental health shows how modern our taboos really are. It is one of many misconceptions about the past shattered by Van Gogh in Auvers, the first “serious” exhibition about the artist’s final days. The show is at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam until September 2023, and then moves to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, where it will run until next February. It is more a moving tribute to a life than a record of an artist’s trudge towards suicide, and is subtly curated – the walls of the final, funerary room are tinged a respectful navy blue, not a solemn black.

Van Gogh’s relationship with Auvers-sur-Oise, the French village where he spent his last 70 days, was similarly short and intense. In the second of three exhibitions marking the 50th anniversary of the Van Gogh Museum, its curators have reproduced the airy Auvers in panoramic rooms, giving paintings, drawings and letters space to breathe. The exhibition feels light, a reflection of van Gogh’s own sense of optimism.

The artist’s time in Arles usually gets all the attention, but Auvers challenges everything we think we know. Producing over 70 paintings in as many days, it was Van Gogh’s most prolific and experimental period. Walking around this exhibition, we see both close-ups and panoramic landscapes, illustrated letters and his first forays into etchings. Some works seem more like palettes, stuffed as they are with different textures, perspectives and colours. Golden yellows, terracottas, and nearly neon oranges – almost as if he’s desperate to fit it all in.

I’ve only ever seen most of these works online; in person, their warmth is almost overwhelming. His painting entitled simply Cows (1890) is the product of an inside joke shared with his physician; his letters and sketchbooks, constructed haphazardly from folded sheets of paper, burst with the promise of life.

Contrary to stereotypes, van Gogh was a social individual, and you can see it in the exhibits. You’ll always find people in his rural scenes – indeed, many of his paintings are named after the location’s landowners. Here was a man desperate to connect, in whichever way he could. Even his late turn to etching – something he approached as a painter, and saw as secondary to his main practice – was in part informed by the collaboration and teamwork it demanded.

The youthful portraits are intriguing. Adeline Ravoux – boldly depicted in blue-on-blue – looks as if she’s waiting for the whole modelling thing to be over. I stifle a snigger at the unintended humour in his adult, manly faces on his Two Girls (1890).

It’s a wonderfully subtle exhibition, which only made it all the more frustrating when people pestered the curators for more gruesome details of the artist’s death. They eyed his last painting suspiciously, reading dark meaning into his “manic” use of colour.

But they go too far, and miss the essential character of this exhibition, which is clear to anyone lucky enough to visit it – that despite what people think they know about him, Van Gogh was an artist whose work is suffused with a fascination for colour, vibrancy and life. A lot of galleries use the “once in a lifetime” tagline. For once, that is completely justified

Van Gogh in Auvers. His Final Months runs at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam until 3 September 2023, and then the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, until 4 February 2024.

Jelena Sofronijevic is an audio producer and freelance journalist, who creates content at the intersections of cultural and political history.