“Rivera’s Paris,” the new exhibit at the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, does a remarkable job of telling the story of the time when Mexican artist Diego Rivera was laying the groundwork in Europe that would turn him into an art world star.

The exhibit places works by Rivera in conversation with pieces by his friends Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani and Tsuguharu Foujita. There are also works by Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida, Paul Cézanne, Dario de Regoyos and others who were influential in Rivera’s development.

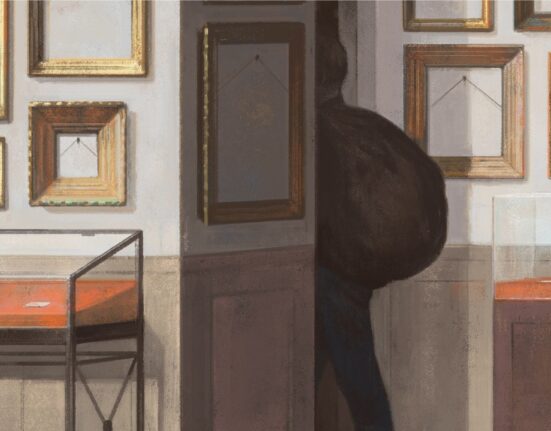

The show, assembled with works from the museum’s stash along with those on loan from 12 other museums and private collections, features 45 paintings, drawings and a few photographs. The centerpiece is “Dos Mujeres (Two Women),” the 1914 cubist masterpiece Rivera painted while living in Paris. It was donated to the museum 70 years ago by Abby Rockefeller Mauzé, daughter of John D. Rockefeller Jr., and sister to future Arkansas Gov. Winthrop Rockefeller. The painting, one of 13 works by Rivera in the show, has been a jewel in the museum’s crown ever since.

“Rivera’s Paris” brings the viewer into the fertile world the ambitious Rivera encountered when he left Mexico for Europe, enthralled by the modernist works of Cézanne and encouraged by Gerardo Murillo, his teacher at Academia San Carlos in Mexico City, who had returned from Europe with reports of the groundbreaking art being made there.

Rivera traveled to Spain for the first time in 1907, and Spain is where “Rivera’s Paris” begins.

The show opens with a bang as viewers are greeted first by two large, eye-popping paintings by Spanish artists. On the left is “Girls of Burriana (Falleras),” a grand oil on canvas from 1910-1911 by Hermengildo Anglada Camarasa that shows three otherworldly, colorfully dressed women and an elaborately adorned horse.

On the right is Ignacio Zuloaga y Zabaleta’s stunning “Lucienne Bréval as Carmen” from 1908, which shows the opera singer Bréval smiling in a magnificently embroidered shawl. It’s the kind of large, figurative painting that can stop someone in their tracks.

Also included is Sorolla’s “The Blind Man of Toledo,” in which the Spanish master captures the light and landscape with loose, beautifully made brushstrokes.

Cézanne, the influential French impressionist (Picasso called him “the father of us all”) who died three years before Rivera’s trip to Europe, was a guiding light for the young artist. There’s a story told in one of the texts accompanying the exhibit of Rivera, who arrived in Paris in 1909, standing transfixed in the rain outside a gallery at the sight of several Cézanne paintings in the window.

Cézanne is duly represented by four pieces here, including “Farm at Montgeroult” from 1898 and the leafy, light “Undergrowth,” both of which should be familiar to regular visitors to the museum; and the sparse, abstract watercolor “Rock Profile Near the Caves Above Château Noir.”

There are several graphite drawings by Rivera, including his 1918 portrait of poet, novelist and filmmaker Jean Cocteau, who Rivera befriended while he and his common-law wife and fellow artist Angelina Beloff visited friends in a village on the Atlantic coast of France.

“Montserrat,” a bright, pointillist landscape from 1911, is a good example of how Rivera was exploring with paint as he sought his own style.

By 1913, he had embraced cubism, and the groundbreaking movement is a crucial part of the exhibit.

Rivera’s pal Picasso is synonymous with cubism, and the show includes the Spaniard’s moody, earthy-toned “Man with a Pipe.” There is also Jean Metzinger’s blocky “Cubist Landscape,” and a hat-tip to the curators for including Beloff’s fun, colorful “Still Life with Bottle.”

Rivera also tackled still lifes in cubist form, including “Still Life, Mallorca” and “Still Life with Bread Knife,” which both have an almost textile appearance even though they are done in oil.

“Dos Mujeres,” of course, is the exhibit’s focal point. In it, Rivera depicts Beloff, who is standing, and their friend Alma Dolores Bastián, a fellow artist who lived with her husband in the same building as Beloff and Rivera in Paris and who is shown seated with a book in hand.

You’re likely familiar with the painting if you’ve ever visited the museum. Seeing it in this context, however, invites a closer look. There is a dog at the bottom and the Parisian cityscape can be seen in the background. Rivera’s use of planes, sharp lines, angles and color is mesmerizing.

By late 1920, Rivera left Paris and returned to Mexico. He became famous for his murals and was married, twice, to artist Frida Kahlo, whose star has probably eclipsed his in recent years (the tagline for the new exhibit is: “Before fame and Frida, there was Paris”). A sub-narrative of the exhibit is Rivera’s relationship to the Rockefellers, and the importance of the donation 70 years ago of “Dos Mujeres.”

The decision to spotlight that painting, along with the assemblage of early works by Rivera and pieces by his cohort and influences, have resulted in an informative and rewarding exhibit, one that connects Arkansas, the museum and the early, formative years of one the 20th century’s most important artists.

“Rivera’s Paris”

- When: Through May 18

- Where: Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, 501 East Ninth St., Little Rock

- Hours: 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesday; 10 a.m.-8 p.m. Wednesday-Friday; 10 a.m.-5 p.m, Saturday; noon-5 p.m. Sunday

- Admission: Free

- (501) 372-4000

- arkmfa.org