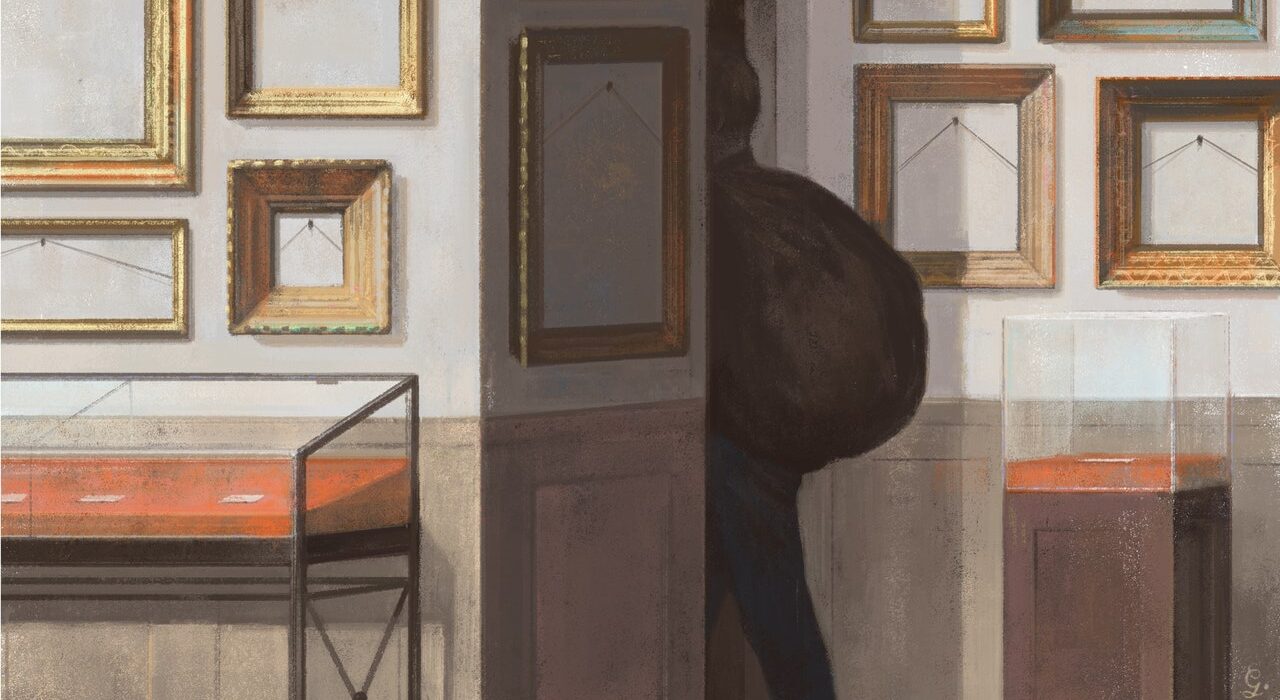

The first thing Stéphane Breitwieser steals from Belgium’s Art & History Museum is an index card. Folded in half and set inside a partially empty display case, it reads, in French, “Objects Removed for Study.” The museum contains one of the largest collections of art and antiquities in Europe, but Breitwieser immediately recognizes that, for his purposes, its most valuable item is the notecard. He jimmies open the case, pockets the card, and, together with his girlfriend and accomplice, Anne-Catherine Kleinklaus, strolls onward. To anyone who happens to notice them, they look like a happy, art-loving young couple enjoying a date at a museum, which, in a sense, they are.

A few rooms later, another display case catches Breitwieser’s eye. This one is filled with fantastically ornate sixteenth-century silver objects, including goblets, chalices, and a miniature warship. The lock, he notices, is high end but poorly installed; he smacks the top and the cylinder drops out of its housing and into the display case. Breitwieser helps himself to two chalices and a tankard, then sets the index card down where they used to be. Only when he and Kleinklaus have reached his car does he realize that he has left the lid of the tankard behind. That won’t do. He is an aesthetic perfectionist; a topless tankard will be a torment to him. Kleinklaus knows this about her boyfriend and, although he is usually the improvisational genius, she can hold her own when circumstances require it. She takes out one of her earrings and returns to the entrance, Breitwieser in tow. When she shows the guard her remaining earring and says she thinks she knows where she lost the other one, he lets them both back inside. At the display case, Breitwieser takes the tankard lid, along with—why not?—two additional goblets.

They return two weeks later. The index card is still in the case. So is the warship, which Breitwieser puts in Kleinklaus’s purse. Then, from the same display, he nicks a two-foot-tall chalice, which he stuffs up the sleeve of his coat, making it impossible to bend his left arm. The pair are on their way to the exit when a guard asks to see their tickets. Kleinklaus’s is at the bottom of her purse, beneath the ship. Breitwieser’s is in his left pocket, which he can’t access with his left hand. He reaches across his body, like a man drawing a sword, fishes out the ticket, hands it to the guard, and explains that they’re just headed to the museum café to grab a bite to eat. The guard waves them on, and they go to the café, sit down with their ill-gotten goods, and have lunch.

Two days later, they come back for more, bringing the total number of artifacts they have stolen from that single display to eleven. Aside from the “Objects Removed for Study” card, the case is now almost empty. On their way out of town, they stop at an antique shop whose front window boasts a beautiful seventeenth-century silver-and-gold urn. Later, back home, Kleinklaus phones the shop and asks how much the urn costs. Around a hundred thousand dollars, the owner tells her, but it’s worth it. “Madame,” he says, “you really must see it.” But of course, by then, the urn is no longer in his window. It is in a modest house in an industrial town in eastern France, in the attic rooms occupied by Breitwieser, Kleinklaus, and some two billion dollars’ worth of stolen art.

All this is recounted, thrillingly, in “The Art Thief” (Knopf), by the journalist Michael Finkel. It is his third book, and also the third one to search for meaning—moral, aesthetic, existential—in criminal acts. This is an interest he comes by honestly, or, more precisely, dishonestly. In 2002, Finkel, who was then a contributing writer at the New York Times Magazine, plummeted from grace when the protagonist of an article he wrote, about allegations of child slavery on West African cocoa plantations, turned out to be a composite character. The Times fired him and soon afterward published a lengthy correction, which took his transgressions from private to public and took a sledgehammer to his reputation.

An hour and a half before that correction ran, Finkel got a phone call from a fellow-reporter. To his surprise, confusion, relief, and horror, the man was not calling about his journalistic offenses; he was calling to ask if Finkel was aware that someone named Christian Longo, who was accused of and would later confess to murdering his wife and three young children in Oregon, had recently been captured in Mexico, where he had adopted the identity of a writer he admired—Michael Finkel of the Times Magazine. Real and faux Finkel began to correspond, and both men’s misdeeds became fodder for the writer’s first book, “True Story: Murder, Memoir, Mea Culpa.” A dozen years later, Finkel published “The Stranger in the Woods,” an account of a man named Christopher Knight, who, for twenty-seven years, lived in the forests of central Maine entirely outdoors and alone, getting by on the haul from a decades-long burglary streak that kept him in both necessities and luxuries: food, clothing, batteries, propane tanks, sleeping bags, mattresses, books, television sets, handheld games.

Now comes “The Art Thief,” which documents a different kind of crime, one that circumvents both the moral horror of murder and the mundanity of petty theft. From 1994 to 2001, Breitwieser, working mostly with Kleinklaus but sometimes alone, stole at a pace unprecedented in the history of art: roughly three out of four weekends per year for eight years, resulting in some three hundred purloined works of art. He plied his craft during business hours, in museums and galleries and auction houses, with tourists and docents and security guards milling around. He never wore a mask and rarely disguised himself at all. He carried no weapons, never hurt anyone, and never threatened to hold anyone hostage. He did not use the art he stole to fund other illegal activities or sustain an extravagant life style. He simply took it home to those attic rooms and admired it.

As illegal activities go, the crime spree of Stéphane Breitwieser was decorous, electrifying, and, for all its outrageousness, familiar. As a form of entertainment, “The Art Thief” has less in common with Finkel’s earlier books than with movies such as “Ocean’s Eleven.” Like that film, it unmistakably belongs to the genre of the heist, a category of entertainment so fun and frictionless that it is easy to skate right past the obvious question it raises. Why, given our over-all disapproval of theft, are stories about heists so appealing—to so many of us, and specifically to Michael Finkel?

A heist, to be clear, is not a legal category. If you are caught with a Rembrandt in your raincoat on the way out of the Louvre, you will not be charged with attempted heist. The term is pure slang, coined in America in the nineteen-twenties, a high-water decade for crimes of all kinds. It likely comes from “hoist,” either in the sense of hoisting someone up to shimmy through a window or in that other sense of picking something up, the one implied by “shoplifting.” But no one has ever described the pilfering of a can of Red Bull and a pack of condoms as a heist; indeed, real-life crimes are only infrequently characterized that way. For the most part, “heist” suggests less a specific illegal action than the form of entertainment that depicts it.

Although the heist genre shares a border with mystery novels, spy novels, true crime, and crime fiction, it has its own distinctive conventions, the first of which is that the object of the theft must be spectacularly valuable. Steal thirty thousand dollars or a Rolex watch and it’s a crime; steal thirty million dollars or the Hope Diamond and it’s a heist. Second, that object must be taken from an institution of significant standing. Heists do not occur at Sunoco stations or suburban homes; they happen in banks, preferably on Wall Street, or museums, preferably the Met. Third, the theft must be borderline impossible. That’s why every heist plot pauses at some point to explain why, for instance, the thieves have to rob not one casino but three at the same time (as in Steven Soderbergh’s 2001 remake of the aforementioned “Ocean’s Eleven,” among the most genre-satisfying of all heist films), or why they have to steal not one car but fifty in less than three days (as in the 2000 remake of “Gone in 60 Seconds,” which features Nicolas Cage and Angelina Jolie in what you might call a car-studded cast: among others, an Aston Martin, a Ferrari Testarossa, a Lamborghini Diablo, a Bentley Arnage, and a 1967 Ford Mustang Shelby GT500). Give or take some paraphrasing, in almost every heist story someone says, “It can’t be done.”

But it can, of course; you just need the right criminals. That’s the fourth convention of the heist: assembling a team. Its members are typically underworld all-stars, each one the master of a highly specialized skill: picking pockets, counting cards, hacking computers, back-flipping over motion detectors, strolling into Sotheby’s with so much savoir faire as to seem like a legitimate customer. Collectively, they illustrate the point, made by, of all people, Aristotle, that just as there are outstanding doctors and musicians there are also “perfect thieves,” who “have no deficiency in respect of the form of their peculiar excellence.” According to a fifth convention, however, when we first encounter these perfect thieves they are wasting their talents on petty chicanery or attempts at moral rectitude; a sixth convention is that at least one of them has retired and must be dragged back into a life of crime for one last irresistible gig. (In a nice meta move, Soderbergh came out of retirement to direct “Logan Lucky”—essentially an Appalachian “Ocean’s Eleven,” in which the West Virginian protagonists set out to rob a Nascar speedway.)