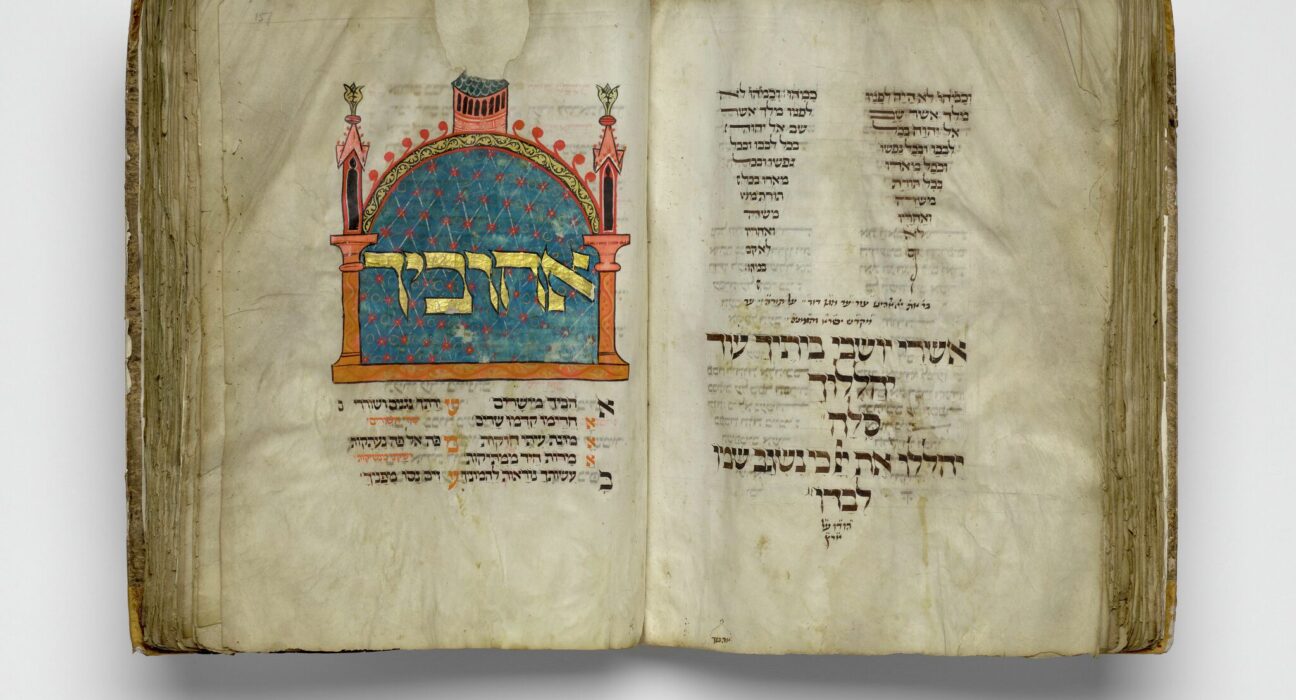

The Montefiore Mainz Mahzor, an illuminated manuscript from Germany dated to around 1310 AD.

MFAHThe Albert and Ethel Herzstein Gallery for Judaica officially opens to the public on Dec. 3. The small gallery, located near the main lobby of the museum’s Caroline Wiess Law Building, currently contains about 30 items in a collection that the museum hopes to continue expanding. Though some of the items in the gallery are on loan or will be rotated out, the exhibit itself is a permanent addition to the museum.

Judaica is the term for Jewish ceremonial art—objects and writings related to Jewish life, ritual, and worship, such as menorahs, Torah mantles, textiles and books. The gallery joins already existing exhibits at the MFAH devoted to the arts of Korea, Japan, India, China, and the Islamic worlds.

Museum director Gary Tinterow said that when he first joined the MFAH in 2012, the museum had only one object classified as Judaica, even though there were hundreds of items in the museum’s collection associated with other religions. That item was a bronze oil lamp from the Mediterranean, dated 400–600 BCE, that the museum acquired in 2005. In 2018, under Tinterow’s direction, the museum acquired a second object: a medieval illuminated manuscript from Mainz, Germany, dated to about 1310 AD.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

With that second acquisition, “The question was, ‘Why don’t we have more?’” Tinterow said.

In 2022, the museum launched a program called the World Faiths Initiative, an effort to bring focus to the religious significance to many objects already in the MFAH’s collection, with a temporary Judaica exhibition in partnership with The Jewish Museum in New York. Coincidentally, around the same time the World Faiths Initiative was being planned, a number of privately held collections of Judaica were being broken up for auction, an acquisition opportunity the MFAH jumped on.

The new gallery brings the MFAH into a small group of encyclopedic art museums in North America that have committed to collecting, displaying and studying Judaica, alongside the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the North Carolina Museum of Art, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Christine Gervais, director of MFAH’s house museum Rienzi and curator of decorative arts, curated the gallery. Beth Schneider, former Head of Learning at the Royal Academy of Arts in London and former Education Director of the MFAH, is a consultant to the project.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

Gervais said she expressed dismay to Tinterow about curating the exhibition since she is not Jewish. “But you’re an art historian, and this is art,” Tinterow told her. Furthermore, the objects in the gallery fall under the purview of decorative arts, Gervais’s expertise, Tinterow said.

Judaica is rare and collecting it can be challenging, Tinterow said, in part because of the many persecutions and displacements Jewish people have endured throughout history. Religious items were frequently destroyed by hostile regimes. Additionally, many ceremonial items were made with precious materials like silver—materials that could be melted down to, say, pay for an escape from a repressive government.

In building the collection the museum wanted to represent the entire Jewish diaspora, with objects from India, Turkey, Libya and Europe. Some items in the collection share the same purpose but have vastly different designs based on where they were made. For example, one spicebox in the exhibit is covered in North African-style enamel work. Another spice box, a fish-shaped object on loan from Houston’s own Beth Yeshurun, is a made from Central European silver, likely from Austria or Hungary.

In addition, some items were clearly made by Christian artisans for Jewish use, because in some places Jews were forbidden from being members of trade guilds. One such object, an oil lamp from Ireland, looks identical to the lamps used in Catholic masses. But this one has Hebrew script on it, likely having been repurposed for use in a temple.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

“It shows engagement with local artistic communities,” Schneider said.

Other items are more personal. A long piece of fabric from 1700s Germany meant to serve as a binder or wrapper for the Torah, is embroidered with the details of a young boy’s birth, along with prayers for his future.

“These objects show us how people lived,” Gervais said.

While many of the items were acquired by the museum thanks to the Herzstein Foundation, for whom the gallery is named, other items are on loan from local synagogues and the Jewish Museum in NYC. Some of the items in the museum’s collection are too delicate to the displayed for long, such as the medieval manuscript that helped kick off the new collection. Over the coming year, the museum will flip pages in the book, and will eventually switch it out for another manuscript. Other items will be returned to their lenders and replaced by new objects. But despite their frailty, the items’ continued existence also shows endurance, according to Tinterow.

Advertisement

Article continues below this ad

The medieval manuscript, for example, is a perfect metaphor for the plight of Jewish people, Tinterow said. Its pages are waterlogged, and some have been defaced. It’s been “beaten up, forcibly migrated” and hidden away for years, and yet, 1,000 years later, it still exists.