November 14, 2023

Frédérique Carrier

Managing Director, Head of Investment Strategy

RBC Europe Limited

RBC Wealth Management’s “Worlds apart: Risks and opportunities as

deglobalization looms” series explores the trend away from globalization

and its ramifications for investors, economies, and financial markets. The final feature in the series explores the reshaping of the semiconductor industry and the investment implications.

Key points

-

The wide-scale disruption of the global semiconductor supply chain

during the COVID-19 pandemic and increasing tensions between the U.S.

and China set off alarm bells within government circles. -

Many governments are focusing on chip security and proposing bold new

incentives to manufacture critical technology closer to home as a

hedge against overreliance on foreign supplies. -

The reshoring strategy, which prioritizes supply chain resilience over

cost efficiencies, should bolster national security, but it comes with

its own challenges. -

Once these challenges are overcome, the industry should benefit from

secular (long-term) growth, though some cyclical (economically

sensitive) elements do remain. Semiconductor equipment manufacturers

could provide a useful hedge to geopolitical tensions heating up.

Semiconductor manufacturing: A truly global industry

Powering everything from emails to advanced military systems,

semiconductors, or chips, are the critical enablers of our modern society

and economy. This prominence has brought them to the forefront of national

security.

Created in the U.S. in the 1950s, the semiconductor industry has evolved

into a highly efficient but deceptively complex, dispersed, and truly

global supply chain. And with each step of the production process, highly

intricate and critical, specialization has developed naturally.

Such a complex supply chain has evolved as the most cost-efficient way to

produce the chips. So long as all the steps ran smoothly, such complexity

was of little to no concern. But after COVID-19 burst onto the scene, many

factories were shuttered during the pandemic, causing wide-scale

disruption. Meanwhile, increasing tensions between the U.S. and China have

also highlighted a number of pressure points along the supply chain,

setting off alarm bells within government circles.

In his book Chip War, author Chris Miller lays out the complex

web of production:

“A typical chip might be designed with blueprints from the

Japanese-owned, UK-based company called Arm, by a team of engineers in

California and Israel, using design software from the United States.

When a design is complete, it’s sent to a facility in Taiwan, which buys

ultrapure silicon wafers and specialized gases from Japan. The design is

carved into silicon using [precision] tools produced primarily by five

companies, one Dutch, one Japanese, and three Californian. […] The chip

is then packaged and tested, often in Southeast Asia, before being sent

to China for assembly.”

In particular, parts of the supply chain are dominated by an uncomfortably

small number of firms. For instance, ASML, a company based in the

Netherlands with a $200 billion market capitalization, builds 100 percent

of the world’s extreme ultraviolet lithography machines, which are

essential to produce the most advanced chips that go into smartphones and

data centers. Two South Korean companies, Samsung Electronics and SK

Hynix, produce more than half of the world’s memory chips. But the biggest

concern is probably the outsized role that Taiwan plays, given it is

caught in the geopolitical crosshairs amid U.S.-China tensions.

Taiwan today manufactures 60 percent of the world’s semiconductors under

the “outsourced foundry” model and 90 percent of the most technologically

advanced ones, the logic chips that perform advanced processing. Moreover,

most are manufactured by a single company, Taiwan Semiconductor

Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC).

Semiconductor primer

| Chip type | Functions | Main manufacturers |

|---|---|---|

| Memory |

Storing data DRAM chips provide temporary data storage. NAND chips are used for long-term data storage. |

South Korea produces 60% of all DRAM chips; Japan produces 20%. More than half of all NAND chips are produced in South Korea. |

| Logic |

Processing data

Leading-edge chips are used in smartphones, personal computers, |

Taiwan currently produces approximately 90% of the most advanced South Korea produces roughly 10%. |

| Discrete, analog, optoelectronic & sensor |

Audio and video signal processing Power regulation Data conversion |

Japan is home to 27% of global production capacity. Europe hosts 22% of global capacity. |

Source – RBC Wealth Management, RBC Brewin Dolphin, Boston Consulting

Group

Taiwan’s prominent role in the semiconductor ecosystem

Taiwan rose to prominence in the 1990s as a hub for semiconductor

manufacturing thanks to the creation of a new “outsourced foundry”

business model: making chips designed by customers. A relentless focus on

research and development (R&D), a successful drive for production

efficiencies, and generous state subsidies propelled the country’s

dominance.

Until the mid-1980s, most large chipmakers both designed and manufactured

their chips in-house. But as chips became more advanced, the cost of

building semiconductor fabrication plants, or “fabs,” escalated. At the

same time, it became apparent that scale and process know-how were

necessary to produce a healthy yield, i.e., a high percentage of

well-functioning chips, at low cost.

With these concepts in mind and with generous state support, TSMC soon

thrived. As it did not design chips, it did not compete with its

customers. In time, most U.S. chip manufacturers ceased making

state-of-the-art chips in-house in order to avoid having to build hugely

expensive new fabs on a regular basis. Instead, those American chip firms

focused solely on chip design, outsourcing the manufacturing process to

TSMC. Technology sharing with the U.S. and Europe also allowed TSMC to

successfully commercialize advanced semiconductor manufacturing. The

company ultimately grew to be the largest chipmaker globally by market

value. TSMC, South Korea’s Samsung, and the U.S.’s Intel are now the only

chipmakers capable of manufacturing the most advanced logic chips.

Yet TSMC finds itself in a precarious position today. Taiwan is in the

crosshairs of U.S.-China tensions and ensnared in the technological and

geopolitical competition between the two rival powers, both of which are

highly dependent on TSMC’s semiconductor supply.

In an effort to protect itself, Taiwan strives to retain its prominent

place in the semiconductor ecosystem. While TSMC is building new fabs in

the U.S. and Europe, it will keep its R&D and cutting-edge technology

at home in Taiwan.

For the many nations and regions, such as the U.S., Europe, Japan, and

China, whose phones, data centers, autos, and telecom exchanges among

others all depend so heavily on semiconductors made in Taiwan, this

presents an uncomfortable situation.

It is impossible to know how U.S.-China tensions over Taiwan will play

out, but they do periodically affect financial markets and supply chains.

The geopolitical tensions, U.S.-China trade disputes, and supply chain

disruptions wrought by the pandemic have made many governments around the

world sensitive to semiconductor supply chain vulnerabilities.

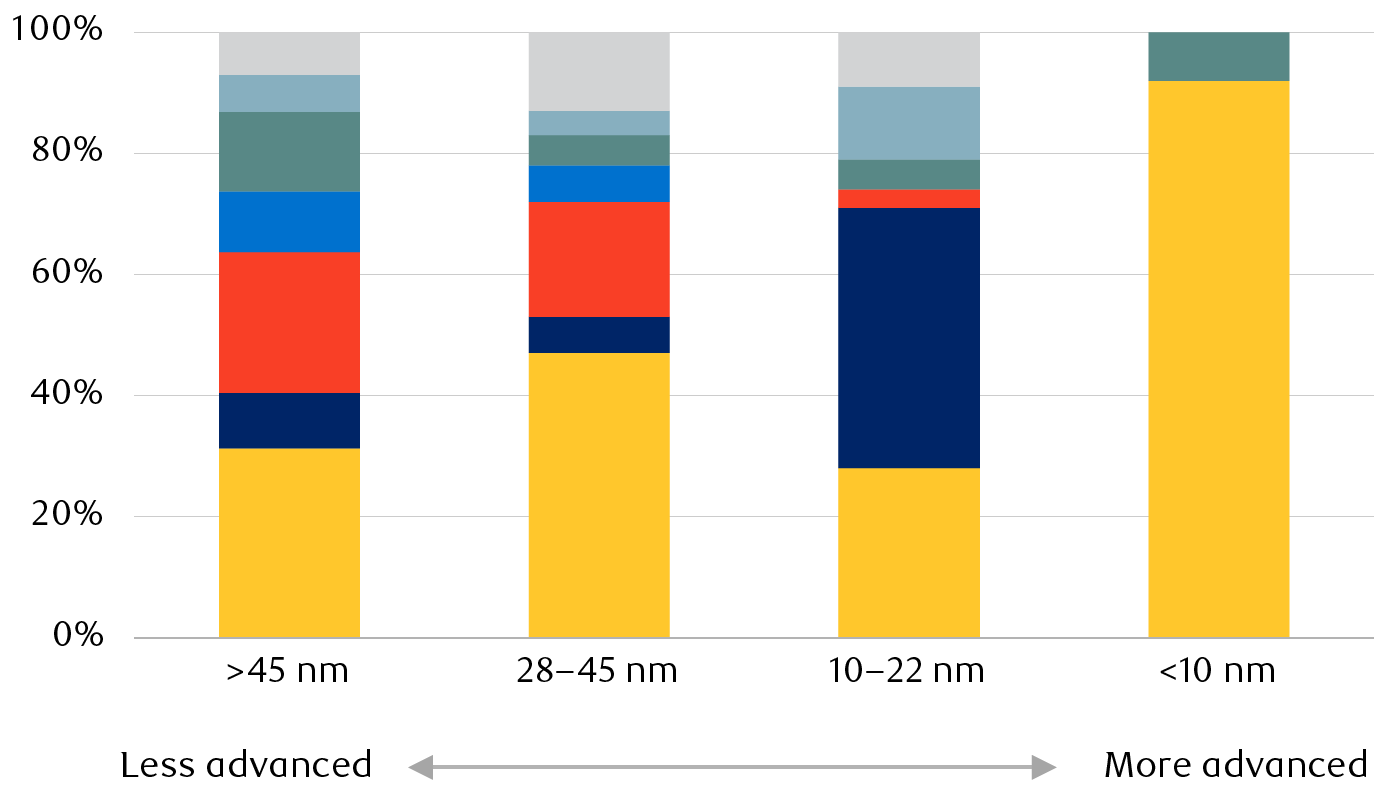

Wafer fabrication capacity for logic chips by country/region, 2019

Taiwan dominates fabrication of the most advanced chips, while China

produces more than 40% of less advanced chips

Column chart showing the percentage of global semiconductor wafer

fabrication capacity by country in 2019 of Taiwan, the U.S., China,

South Korea, Japan, Europe, and all other countries combined.

Fabrication capacity is broken down by wafer feature size: greater

than 45 nanometers, which requires the least advanced manufacturing

technology; 28 to 45 nanometers; 10 to 22 nanometers, and less than 10

nanometers, which requires the most advanced technology. Production of

the wafers with feature sizes less than 10 nanometers is dominated by

Taiwan, with 92% of global capacity (the remainder is produced by

Japan), and Taiwan also produces more than 20% of wafers in all other

categories. The U.S. is the largest producer of wafers in the 10 to 22

nanometer range (roughly 30% of global capacity), but produces a much

smaller proportion of less advanced wafers, and none with features

under 10 nanometers.

-

Taiwan

-

U.S.

-

China

-

South Korea

-

Japan

-

Europe

-

Others*

Note: A wafer is a thin slice of semiconductor material used to

manufacture chips. Fabrication capacity includes wafers for memory and

logic as well as discrete, analog, and optoelectronic & sensor

chips.

* “Others” category includes Israel, Singapore, and the rest of the

world.

Source – Boston Consulting Group, based on data from the SEMI global

fab database

Security through subsidies

Many governments are focusing on chip security and proposing bold new

incentives to fund and safeguard domestic semiconductor manufacturing

industries. They have been backing this strategy with money and plenty of

intervention. The aim is to manufacture critical technology closer to home

as a hedge against overreliance on foreign supplies.

RBC BlueBay Asset Management estimates total incentives towards the chips

industry over the period 2014 to 2030 are in the range of $350 billion to

$400 billion for the U.S., Europe, China, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, and

India.

Subsidies are often looked at skeptically by economists as they tend to

lead to a misallocation of capital. While there is certainly some truth in

this, the brief history of the chips industry suggests that advances in

semiconductor technology are often successful when supported by generous

government grants, as was the case in Taiwan. Below, we look at the use of

subsidies in China, the U.S., and Europe.

Key government incentives for the semiconductor industry

| Metric | Taiwan | S. Korea | Japan | China | U.S. | EU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share of global wafer fabrication capacity | 20% | 19% | 17% | 16% | 13% | 8% |

| Program | Statute for Industrial Innovation | K-Chips Act | National Semis Project | 14th Five-Year Plan | CHIPS and Science Act | European Chips Act |

| Time frame | 2023–2039 | 2022–2031 | 2022–2025 | 2021–2025 | 2022–2026 | 2022–2030 |

| Broad value of incentives (USD billions) | $15–$20 | $55–$65 | $10 | $150 | $74 | $49 |

Source – RBC Wealth Management, RBC BlueBay Asset Management, Boston

Consulting Group, Semiconductor Industry Association

China

China was the first country to actively and openly reduce dependencies on

foreign-made chips and encourage the development of a domestic industry.

It launched the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, also

known as the Big Fund, in 2014 to encourage technological self-reliance.

It initially poured $50 billion into chipmaking, aspiring to meet 70

percent of domestic chip demand by 2025. In total, $100 billion to $150

billion will be allocated in China’s quest to catch up with global

technology leaders.

China entered the industry decades after the U.S., but with generous

subsidies along with wooing expertise and executives from Taiwan (and,

according to Miller’s book, allegations of industrial espionage), it now

manages to produce a growing share of the world’s chips – though its focus

so far has been mostly on less advanced chips. Since 2014, the Big Fund

has nurtured domestic champions such as Semiconductor Manufacturing

International Corporation (SMIC), a producer of logic chips, and Yangtze

Memory Technologies Company (YMTC), a manufacturer of memory chips for

data storage.

Despite efforts at promoting its domestic semiconductor industry, China

hasn’t quite achieved self-reliance yet. China notably spends far more

importing semiconductors than oil. It imported some $400 billion worth of

semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment in 2021 – about

twice as much as it spent on oil. The country’s large domestic market is

an advantage, however, in that it should enable it to reduce production

costs significantly and increase its market share for less advanced chips.

China’s R&D investment has risen dramatically to rival that of the

U.S.

Gross domestic spending on research and development (USD billions)

Line chart showing annual gross domestic spending on research and

development activities since 2000 by the U.S., China, the European

Union, the UK, and Canada. The U.S. is the biggest spender, from $360

billion in 2000 to over $700 billion in 2021. The EU ($230 billion in

2000, $400 billion in 2021) has largely kept pace with the U.S.,

although the U.S. has increased spending more quickly since

approximately 2012. China’s spending has dramatically increased, from

$35 billion in 2000 to $620 billion in 2021, just behind the U.S. The

UK and Canada have maintained annual spending levels below $100

billion since 2000.

Source – Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

United States

As part of its more vigorous industrial policy, the U.S. announced the

CHIPS and Science Act in 2022. First proposed under former U.S. President

Donald Trump’s administration, and then championed by President Joe Biden,

it is a bipartisan effort which aims to respond to China’s focus on the

industries of the future. It proposes some $52 billion in subsidies to

support the expansion of local semiconductor manufacturing capacity.

Three-quarters of the funds will be dedicated to building and upgrading

semiconductor manufacturing facilities. The legislation also includes

another $24 billion worth of tax credits for chip production.

Thanks to these incentives, semiconductor companies are building fabs in

the U.S. TSMC has a new facility under construction in Arizona, and

intends to triple its investment in the state to $40 billion, planning to

open another fab in 2026. Samsung is also planning to build a fab in

Texas.

But it is not only foreign chip manufacturers that will benefit from the

CHIPS Act. Intel, the U.S.’s semiconductor champion, also appears poised

to benefit from U.S. policymakers’ support as it doubles down on its

manufacturing capabilities via two state-of-the-art fabs it is building in

Arizona and Ohio, investing $20 billion in each. Beyond that, other U.S.

players are jumping back in with new fabs of their own in the works.

Europe

The EU has its own landmark plan to beef up its chip industry. The

European Chips Act aims to generate public and private investment worth

€45.75 billion ($49 billion) in semiconductor R&D and production. The

scheme intends to double the EU’s share of the global semiconductor market

to 20 percent from 10 percent by the end of the decade. Some €35 billion

($37.5 billion) will be allocated for mega fabs, with the rest going to

chip-design platforms and other infrastructure. As a result, TSMC, in a

joint project with three European companies, announced it will construct a

€10 billion ($10.7 billion) plant in Germany. TSMC is linking up with

Bosch, a German auto supplier, as well as Infineon Technologies and NXP

Semiconductors, two chip manufacturers from Germany and the Netherlands,

respectively, to build a factory near Dresden in response to customer

concerns over geopolitical tensions. This follows a similar move by Intel,

which is planning to build two wafer fabs in east-central Germany.

Europe’s semiconductor industry doesn’t have as high a profile as that

of the U.S. That may be because more than half of the continent’s

capacity is for chips with structures measuring at least 180 nanometers

(1 nanometer equals 1 billionth of a meter), much larger than the most

sophisticated chips produced by TSMC and Samsung, which measure just a

few nanometers wide. But the latter are mostly used in consumer

electronics, whereas the larger European structures are used by the

continent’s industrial firms, which need them for applications spanning

autos, machine tools, and sensors. In a way, Europe’s largest

chipmakers, such as Infineon and STMicroelectronics, focus on their

local customer base.

Fab idea but will it work?

While reshoring some production may be practical, it is difficult to

conceive that all production of logic chips can be successfully moved

closer to consumer points.

Yes, the subsidies that governments are pumping into their chip industries

are substantial and a promising step. Still, they are clearly insufficient

to uproot an ecosystem developed and fine-tuned over four decades, in our

view. Moreover, government efforts are aiming to replicate a business

model that companies – focused on optimizing capital utilization – had

previously chosen to exit by offshoring.

The reshoring strategy, which prioritizes supply chain resilience, should

bolster national security. But in November 2022, CNN reported that at a

press briefing, Morris Chang, founder of TSMC, commented that the cost to

manufacture chips in the U.S. would be 55 percent higher than in Taiwan.

Another big hurdle is a talent shortage. Having outsourced and offshored

the process of turning silicon wafers into electronic circuits at scale to

Asia, the U.S. finds itself low on skilled workers to build, operate, and

run the new fabs. A worker shortage could result in either higher labour

costs or a factory running below capacity. The start of production at one

of TSMC’s new fabs in Arizona was pushed back by a year to 2025 due to

several challenges, chief among them being a lack of workers with suitable

skills.

Working in close collaboration with semiconductor companies, universities

and community colleges are creating new fields of study to address these

staffing issues, including some shorter programs with hands-on experience

for both undergraduate and graduate semiconductor degree programs. TSMC

may also send some of its own technicians from Taiwan to train its

American staff.

Over time, the industry’s hope is that labour shortages wane as the skilled

workforce grows.

Maintaining a leading edge through restrictions

The U.S.’s semiconductor policy isn’t solely based on subsidizing local

manufacturing processes. It also aims to stymie China’s efforts at

developing advanced chips, so that the U.S. can retain its technological

superiority. In particular, the U.S. is concerned China may be developing

technology which could give it a military edge. Washington has closed down

paths that have enabled China’s technological rise. In 2022, the Biden

administration banned the export of all advanced semiconductor chips and

equipment to Chinese companies on the grounds of national security. It

also pressured allies, such as the Netherlands and Japan, to follow suit.

The Dutch government, which had already restricted exports of the most

advanced semiconductor equipment to China in 2019, increased the scope of

technology that would fall under export controls. In October 2023, the

U.S. tightened export restrictions further to include leading-edge

artificial intelligence chips.

China retaliated by imposing export controls on gallium and germanium, two

critical minerals used in high-end semiconductors. China is the

overwhelming producer of these rare earths, accounting for 90 percent and

60 percent of global production, respectively.

It is likely that U.S. restrictions on the export of advanced chips have

spurred China’s resolve to support its domestic semiconductor industry.

After all, the U.S. could expand its restrictions to include less advanced

technology, a move that would mean semiconductor capacity in China could

become difficult to maintain and service. Chinese companies, encouraged by

ample state funding, have thus redoubled their efforts to develop their

own versions of chip technologies imported from the U.S., seeking to limit

the impact of U.S. restrictions.

China may have found a way around the U.S. export ban on cutting-edge

chips that come from foundries using American technology. It was recently

revealed that Chinese tech giant Huawei and SMIC seem to have been able to

manufacture 7-nanometer (nm) chips, only two generations behind TSMC’s and

Samsung’s 3 nm nodes.

Positioning for the semiconductor manufacturing industry reshoring

The surge in investment in the semiconductor industry is happening at a

time when there is a glut of chips. This is typical of the notoriously

cyclical chips industry. It takes a few years to construct a fab and bring

it online, by which time the demand trends may no longer be as strong as

when the decision to build was taken. Semiconductor product lifecycles

tend to be short due to technological innovation, particularly at the

leading edge. The new subsidies and investments into reshoring are

turbocharging the current cycle, with supply being boosted just as America

is reducing the sale of all U.S.-made advanced semiconductor chips and

chip equipment to China. Sales to China will not be easily replaced – the

country is the second-largest market for many U.S. firms. For instance, it

represents slightly over a quarter of 2022 revenues at NVIDIA and Intel.

Once these challenges are overcome, new applications, such as artificial

intelligence, and greater chip content throughout the economy should

enable the semiconductor industry to grow by mid-single digits through

2030, in our view. The industry should benefit from secular (long-term)

growth, though some cyclical (economically sensitive) elements do remain.

Semiconductor equipment manufacturers also operate in a cyclical industry,

but they enjoy a much stronger backlog and healthy order book, given the

new fabs being built on the back of the reshoring trend. Should

geopolitical tensions flare up over Taiwan, this segment could provide a

useful hedge. Still, it is not entirely immune to geopolitical risk – when

reports came out that the U.S. would restrict exports of semiconductor

equipment to China, the share prices of U.S. tool makers, which generate

one-third of sales from China, duly corrected. But the strong order books

provide some degree of cushion, and share prices have since recovered.

As for Asian semiconductor manufacturers, RBC BlueBay Asset Management

Emerging Markets Portfolio Manager Guido Giammattei has noted their

returns could potentially be diluted by the lower return on investments

outside of Taiwan and China. The impact would be marginal, in his view, as

this new capital expenditure and related capacity will be gradual and

relatively small. For instance, TSMC’s U.S. factories could produce

600,000 wafers per year, versus total capacity of some 15 million wafers

per year. To a large extent, the impact of new capacity on returns is

already reflected in current industry valuations, in his view.

Furthermore, Giammattei believes the U.S. government’s friendshoring

strategy should encourage further supply chain relocations into Southeast

Asian nations such as Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia, given the region’s

supportive policies, cost competitiveness, and ties to existing

manufacturing hubs. Nearshoring also presents a distinct opportunity for

Mexico to expand its economic role and to become the leading supplier to

North America.

Overall, the broad semiconductor sector awaits a favourable cyclical entry

point, which may be delayed by what we see as a likely recession on the

horizon. But with the prospects of new applications, greater chip content,

and further strength in semiconductor equipment order books on the back of

government support and rising technological complexity requirements, we

think investors should now consider this specialized sector for global

equity portfolios, particularly with the need for governments to be less

reliant on Taiwanese supply, as tensions regarding Taiwan might flare up

from time to time.

With contributions from Nishad Subramaniam, CA, CFA, Senior Analyst,

Technology and Industrials, RBC Brewin Dolphin.

The material herein is for informational purposes only and is not directed at, nor intended for distribution to or use by, any person or entity in any country where such distribution or use would be contrary to law or regulation or which would subject Royal Bank of Canada or its subsidiaries or constituent business units (including RBC Wealth Management) to any licensing or registration requirement within such country.

This is not intended to be either a specific offer by any Royal Bank of Canada entity to sell or provide, or a specific invitation to apply for, any particular financial account, product or service. Royal Bank of Canada does not offer accounts, products or services in jurisdictions where it is not permitted to do so, and therefore the RBC Wealth Management business is not available in all countries or markets.

The information contained herein is general in nature and is not intended, and should not be construed, as professional advice or opinion provided to the user, nor as a recommendation of any particular approach. Nothing in this material constitutes legal, accounting or tax advice and you are advised to seek independent legal, tax and accounting advice prior to acting upon anything contained in this material. Interest rates, market conditions, tax and legal rules and other important factors which will be pertinent to your circumstances are subject to change. This material does not purport to be a complete statement of the approaches or steps that may be appropriate for the user, does not take into account the user’s specific investment objectives or risk tolerance and is not intended to be an invitation to effect a securities transaction or to otherwise participate in any investment service.

To the full extent permitted by law neither RBC Wealth Management nor any of its affiliates, nor any other person, accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this document or the information contained herein. No matter contained in this material may be reproduced or copied by any means without the prior consent of RBC Wealth Management. RBC Wealth Management is the global brand name to describe the wealth management business of the Royal Bank of Canada and its affiliates and branches, including, RBC Investment Services (Asia) Limited, Royal Bank of Canada, Hong Kong Branch, and the Royal Bank of Canada, Singapore Branch. Additional information available upon request.

Royal Bank of Canada is duly established under the Bank Act (Canada), which provides limited liability for shareholders.

® Registered trademark of Royal Bank of Canada. Used under license. RBC Wealth Management is a registered trademark of Royal Bank of Canada. Used under license. Copyright © Royal Bank of Canada 2023. All rights reserved.

Managing Director, Head of Investment Strategy

RBC Europe Limited