A scruffy, seemingly ordinary desk sits in a corner at the Syracuse University School of Architecture. Its laminate surface is marked by scuffs and coffee-cup rings accumulated over nearly seven decades; its surface has been warped by the weight of books. The frame is made from indeterminate wood, roughly coated in metallic paint, perhaps added to make a humble piece appear expensive. Much of it is damaged; all of it is fragile.

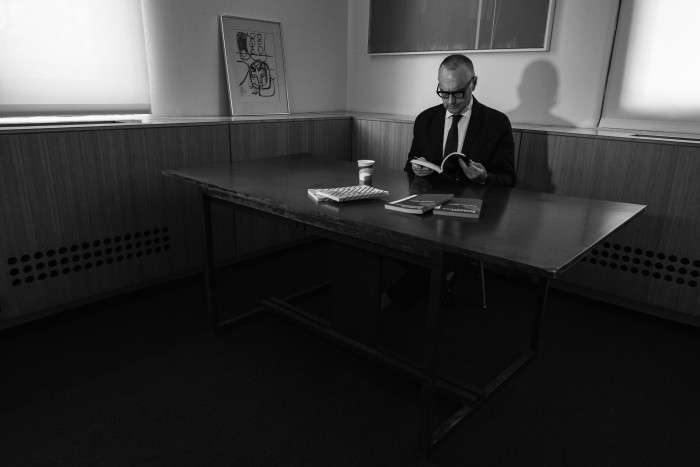

It may seem an unlikely piece of furniture in a prestigious school. But the desk’s symbolic value is immeasurable, says dean Michael Speaks.

“Everyone who comes here wants a photograph of themselves sitting behind it,” he says. “It’s an incredible attractor.” Students hang out in Speaks’s office “just to look at it”.

They are drawn by its mystique. The desk once belonged to Marcel Breuer, the Bauhaus-trained architect and designer, who designed it himself in 1956 and used it until his death in 1981 (he called it “Desk No 2”). Conceivably — though there is no proof — he made drawings for countless masterpieces such as 945 Madison Avenue in Manhattan, aka the Breuer Building, on its tatty, laminate surface.

Syracuse, which also holds about half of Breuer’s archives, acquired his desk in 2019 as a gift from a benefactor. It is still in service — Speaks uses it to spread out posters and drawings.

Physical evidence, including original designs and surviving photographs of Breuer sitting behind it, give the desk substantial monetary value: as high as $250,000, according to a 2019 report cited by Speaks.

Desks that were once the property of famous or notable people intrigue us, perhaps in ways other relics do not. They bear witness to — and, we might hope, retain traces of — the geniuses who once laboured at them. According to experts, a reliquary of a genius can command a high premium, almost impossible to predict. Secret drawers, accessories, scratches or scraps of remaining paper can all help raise the price.

“It’s about as close as you can get to the person without buying the actual person,” says Charlie Thomas, UK group director for house sales and private and iconic collections at Bonhams. “That’s what makes these sales so exciting. It’s very difficult to second guess the uplift that people are willing to pay. The value is decided by the fans.”

In recent years, otherwise unremarkable pieces have far exceeded estimates at auction, including cast-offs that once belonged to Joan Didion, Sir Michael Caine, Sir Roger Moore, John le Carré and many more. In Los Angeles, a squat, faintly Art Deco style desk in ebonised birch at which Jackie Collins wrote many of her wildly popular raunchy novels, sold in 2017 for £5,500 — more than twice its lowest estimate.

“Ordinarily, that’s something we wouldn’t sell . . . it would probably be a tenth of that without the provenance,” says Thomas.

Didion’s desk, which she used at home, sold last year for $60,000. Her desk accessories sold for nearly $20,000.

A battered desk designed and used by Sir Terence Conran, the British product designer and retailer, was among several sold at his London estate sale last year for £2,200 — nearly three times its lowest estimate. A walnut desk, also designed by Conran and made by Benchmark Furniture, sold for £20,400.

Perhaps the most striking premium was achieved by the desk at which Hilary Mantel wrote her Wolf Hall trilogy, which, judging by its catalogue picture, looks like any bog-standard self-assembly number in marmalade pine. It fetched more than £5,000 last year.

Even the smallest desk takes on talismanic qualities if it once belonged to a professional hero or heroine. About 15 years ago, Thom Brisco, now director of a London-based architectural practice, was working as a trainee when he volunteered to help clear out his boss’s office.

“There was this collection of relics, things he had gathered across time,” he says. “And he had this one unit. I hadn’t seen it before, but as we were taking it out, my boss explained its history.”

The unit was a 1970s desk extension in creamy white plastic — “a solid little block of a thing” — mass manufactured in Italy by Stile Neolt. It was unremarkable and, unlike Breuer’s desk, came with no formal provenance. But to Brisco its lineage was priceless.

Brisco’s boss was the architect Jamie Fobert, who explained to him that the extension had once belonged to the Pritzker prizewinning international architect Sir David Chipperfield. Brisco believes Chipperfield used it, possibly as a student, and gave it to Fobert when he was a junior employee.

“I asked Jamie if I could have it and he gave it to me,” says Brisco. “I think he regretted it later.”

“Somehow it just followed me around, like a little droid. Now I’m trying to start a small office, and it sits there as a reminder that I once worked with Jamie, and Jamie worked with Chipperfield.” Today, Brisco uses his hero’s desk cabinet to store drawings.

But a desk’s value does not always lie in a former owner with an illustrious name. In the fine furniture market, “it is not necessarily the person who owned it that defines the importance of the piece, but the commissioning that went into it,” says Sebastien Holt, UK director of Modernity, a gallery specialising in 20th-century Modernist furniture.

Holt sells one-off desks often by Nordic designers, such as a recently sold piece in pearwood and ivory designed by Jarl Eklund, the Finnish architect, in 1924 for a noble Helsinki family called Hisinger.

“We don’t know much about them. It was special not because of them, but because of who designed and commissioned it,” says Holt.

Fine pieces commissioned by famous designers for their own use are often the most coveted of all. At the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht this year, crowds gathered around another unique piece, a dazzling Art Deco desk that once belonged to Paul Dupré-Lafon, one of France’s leading architects and furniture designers, made to his specifications in 1928. It took centre stage in Parisian dealer Galerie Marcilhac’s stand.

Dupré-Lafon, who has been described as the “decorator of millionaires”, was known for expensive lamps, ashtrays and so on in the functionalist style, designed for the private homes of 20th-century Parisian society. His sizeable desk of black pearwood came with accoutrements: a scarlet-leather insert and an inlaid tray that made paperwork disappear at the touch of a slim brass handle; a chunky swivel-chair, also in red leather; a light-fracturing desk lamp; even Dupré-Lafon’s pearwood waste-paper bin.

Other desks are acquired by museums and academic institutions for their sheer originality.

Chelsea College of Arts in London, for example, owns the “Flying Trowel” desk and chair, prototypes by Barney Bubbles, the graphic designer who once worked for Conran and went on to design album covers for Hawkind, The Damned and Elvis Costello, among others.

Bubbles’ desk, commissioned by record company boss Jake Riviera in 1981, is shaped like a bricklayers’ trowel propped up by a pile of wooden blocks that resemble a stack of books — a visual joke, perhaps a provocation on the futility of deskwork. Chelsea acquired the desk to serve the college’s MA curating and collections students, who learn by proximity to examples and object handling, says Donald Smith, former director of exhibitions (it is currently in storage awaiting restoration).

Perhaps, in an era of atrophied working arrangements — co-working, hot-desking, kitchen tables at home — a big, autonomous, permanent, private desk appeals to our deepest fantasies of status and success. If it is imbibed with the presence — or even the ink spills — of an illustrious former owner, so much the better.

Eventually, Syracuse will have to address the dilapidated state of Breuer’s desk. But then, conservation presents a problem, says Speaks.

“With these things, the last thing you want to do is refurbish them,” he says. “There is patina. And if, by some osmosis effect, Breuer’s genius has seeped into the desk, well, that would be finished.”

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTProperty on X or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram