When priests at the Krishnaswamy temple in Attingal in southern Kerala summoned gods through rituals, a young A Ramachandran watched in quiet wonder. Years later, his sculptures still reflect those cosmic arrangements — the precision with which the sanctum was adorned for worshippers to be mesmerised by the idol that shone in the light of flickering lamps in the otherwise dark altar.

Ramachandran, 88, has evoked the yantras in his work every now and then. At the Vadehra Art Gallery in Delhi, his Buddha-like bronze is meditative in the centre of an assemblage of figures that come together to form a six-pointed star or shatkona yantra, symbolising the union of masculine and feminine energies in Bahurupi (2006). “This more or less is my last show,” says the artist about the retrospective of his sculptures. Seated in his studio in Delhi, he rues that his vision has been severely impaired by multiple COVID infections. Among the incomplete projects is a series dedicated to the Eklingji temple complex near Udaipur. Its setting reminded him of the lakes around Mount Fuji in Japan. “I could complete only nine out of the set of 11 paintings that I had planned. I also wanted to write about them,” adds the 2005 Padma Bhushan awardee.

*****

It was a chance encounter with Ramkinkar Baij’s iconic sculpture Santhal Family (1938) — depicting a Santhal couple with their child and a dog moving with their possessions in search of opportunities — that took Ramachandran to Santinketan in the late ’50s. “I had planned to go to Madras to study, when a professor (at Kerala University) recommended that I go to Santiniketan and showed me a photograph of Santhal Family. That was the first time I saw a work that had the qualities of an Indian sculpture, and I was awed by how a great work can touch you even as an image. It was then that I decided to go to Santiniketan,” recalls Ramachandran. Under the tutelage of stalwarts such as Benode Behari Mukherjee and Baij, he would discover his own artistic vocabulary. The principles of free expression that his teachers instilled have remained instrumental to his artistic endeavours. On a scholarship to study Kerala mural art in Santiniketan, he recalls how students would learn all mediums. “The difference between Santiniketan and other art schools was that it never taught art. Students were exposed to all media and techniques and encouraged to wander, experiment, make their own discoveries and choose what interests them,” says Ramachandran.

Though his philosophy of life was nurtured by academic training, the darkness he encountered on the streets of Kolkata teeming with refugees in post-partition Bengal was also to leave an indelible mark. The postgraduate in Malayalam literature was well-versed with the writings of authors such as Vaikom Muhammad Basheer, Saadat Hasan Manto and Fyodor Dostoevsky, and in the disquietude of their words he began to hunt for his imagery. “Dostoevsky’s writings haunted me, and I thought I would paint like Dostoevsky wrote,” says Ramachandran.

Consequently, his dark and tortured images reflected pain and misery. If in Kali Puja (1972) the terrorising figures responded to the Naxal movement, End of Yadavas (1973) warned of an apocalyptic future. His version of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, in 1968, had headless men around a table with their hands raised and an emaciated Christ under the table. “In Calcutta, I was exposed to the miseries of life which I had never experienced in Kerala. At the Sealdah Station (Kolkata), in such a small area every activity of human life was happening — birth, death, people eating, sleeping. It appeared remarkable to me that human beings could live in such a degenerating atmosphere,” he says.

The grotesque works of the young artist caught the attention of Virendra Kumar of Kumar Gallery at a group exhibition in AIFACS in Delhi in 1963-64. Ramachandran accepted his offer to shift to Delhi and work for him for a stipend of Rs 1,000 a month. “At the time, my scholarship in Santiniketan was ending, and I could not have imagined making a career only as a professional practising artist,” recalls Ramachandran. It took longer to find the comfort of home in the Capital. “There were a lot of artists in the city, including Ram Kumar, Tyeb Mehta, Krishen Khanna. None of us were earning much money as artists and all of them were very kind to me and helped me settle, but somehow, I could not relate with their value system. They were all interested in the European avant-garde. Modernism was measured on the basis of how much you were adapting from the Western masters; an artist inspired by Indian aesthetics was looked down upon,” says the artist.

In 1965, he joined Jamia Millia Islamia University as a lecturer in art education. “When I was selected, the vice-chancellor, professor Mohammad Mujeeb, said, ‘Nair saab, you will help us to make Jamia another Santiniketan’. That motto guided me for the 28 years I was there,” says the artist-pedagogue who introduced his students to different art traditions and mediums and the history of art just as his teachers had, and worked towards the establishment of the Faculty of Fine Arts in Jamia with artist-colleague Paramjit Singh. Artist Manisha Gera Baswani, who studied art in Jamia and also pursued her National Scholarship (1991-93) from the Government of India under Ramachandran’s supervision, says, “A bright-eyed art student embarking on my BFA in visual arts at the Jamia Millia Islamia University in 1986, I, like most youngsters pursuing arts, was very influenced by the Western art movements. Ramachandran sir, a teacher and an institution in his own right, was a giant presence at the beginning of my student life. His own immersive art practice, in-depth knowledge and pride in our rich cultural heritage as well as the intuitive ability to weave it as a tapestry of artistic wealth and learning allowed for us to shift our gaze.”

To inspire children to dream, with artist wife Chameli, Ramachandran illustrated several children’s books inspired by traditional art forms. “As kids, we grew up in nature, surrounded by grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins. I listened to stories from my grandmother, played near the river, climbed trees, collected flowers for festivals — these experiences influenced my sensibilities. Children growing up in nuclear families don’t have these experiences. When Chameli and I started designing books, we took the role of a grandparent for our children,” he says.

*****

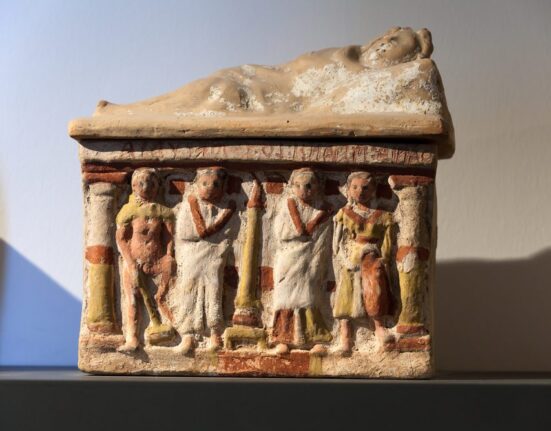

Widely regarded as one of India’s foremost artists at the time, when Ramachandran decided to alter his oeuvre to paint a more lyrical imagery in the ’80s, the pursuit was met with abundant criticism. The resolve itself was provoked by violence. During the 1984 anti-Sikh riots, standing on a terrace he saw a mob chasing a Sikh and thrashing him to death. “I had never seen anything like this. The violence I had witnessed was so brutal. I did not see any point in painting more violence, it wasn’t useful for humanity. Instead of painting more darkness, I asked myself, why don’t I paint more soothing images that would let people forget their miseries and lift up their spirits,” recalls Ramachandran. It took him more than two years to create the monumental Yayati, also intended to provoke the art community to “look inward”. A retelling of a story from the Mahabharata, with Yayati as a modern man’s symbol, it was conceived as the inner shrine of a Kerala temple with 13 bronze sculptures surrounded on three sides by 60 ft painted murals. His inspirations included the Ajanta murals, Harappan dancing girl, Hoysala sculptures, Kerala murals, miniatures and the nomadic Lohar tribe.

Disapproved for being overtly decorative, the work was condemned for its radical departure from his politically explicit works. “I was accused of taking modern Indian art 200 years backwards. It was as if I had done a criminal act. My works were described as decorative, and people said my colours were gaudy and cheap. I was suddenly an outcast and was rarely invited for exhibitions,” says Ramachandran. He adds, “The problem is we mix politics with art in an awkward manner. You can’t sing a protest song and become Bhimsen Joshi. If you want to be Bhimsen Joshi, then you have to sing classical music with its own rhythm and pattern. It is the same with art. There is a distinction between propaganda and art and a painting does not become great because of its subject. Guernica (Pablo Picasso, 1937) is not a great painting because of its theme of war but because of how it has been painted.”

Most Read

After its debut in 1986, Yayati was shown in 2002. By this time, Ramachandran’s mysterious women in natural settings, painted amidst green floral foliage and fauna had gained acceptance. He had also acquainted himself with the simple life led by the Bhil community and discovered the lotus ponds that also became his recurrent leitmotif. “People in the city are conditioned by societal norms. We live in an artificial society but among the tribals I found an open society. The Bhils, for instance, live in complete harmony with nature. I would attend their ceremonies, watch them closely, sketch their life and rituals; they became a part of my paintings.”

Every year, Ramachandran would visit Udaipur and its villages. His last visit was in 2020-21, when he also painted his last set of lotus ponds, exhibited in Delhi in November 2021. On the easel in his studio is an incomplete nayika. Looking at her, he vividly recalls his first portrait and model, sketched on the walls of his home when he was seven or eight years old. “We had a help who treated me like her own child. One day, she asked me to make her portrait instead of scribbling on the walls. I referred to her as my Mona Lisa in my writing, even though she wasn’t pretty like Mona Lisa. She was old, had drooping breasts and used to tie a turban on her head like a man. She was the first woman I drew,” recalls the artist.

‘As A Humanist, He Is Always Concerned About People’

An inspiring educator and fiercely independent in his outlook, A Ramachandran’s work always stood out from the mainstream. Assimilating non-European modernism, even his early works reflected his interest in oriental traditions. Be it the Mexican muralists he discovered in Santiniketan or the temple murals of Kerala. Critical of the social structures that modernity perpetuated, as a humanist he was always concerned about the people at the bottom of the social pyramid and was, in some ways, disillusioned that modern art in India was not addressing that inequality. Though it is largely believed that his early period was strongly modern and later he moved away, one must realise that his work always had traditional elements, and when in the later period he is painting the Bhils and the lotus ponds that he encountered in Udaipur, he is also addressing their predicament. For instance, the lotus pond becomes a metaphor for what is happening across the world with regard to ecological degradation. He did not proclaim these insights but there are aspects of his work that are vastly overlooked. They are much more complex than they appear.

R Siva Kumar, art historian and curator

(As told to Vandana Kalra)